In Milwaukee, subsidies called tax incremental districts — or TIDs — have helped fund the Milwaukee Bucks’ Deer District development, Northwestern Mutual’s downtown campus and The Hop streetcar system.

Alder Russell Stamper II, who represents some of Milwaukee’s poorest census tracts, thought the tool could have an impact outside downtown.

“My district needs the most development, my district needs the most investment,” he said as he described his thought process to WPR. “Why can’t we draw up a TID for a neighborhood?”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Now, thanks to the city’s unusual twist on the common TID subsidy, 74 affordable homes are going up on vacant lots in Stamper’s district. Local developer Emem Group is building 40 of them in 20 duplexes. Milwaukee Habitat for Humanity is building 34 as single-family houses.

Twenty-four homes are already up since the TID was created last summer, said Habitat’s CEO Brian Sonderman.

Inner-city construction is financial challenge

Building affordable homes in Milwaukee’s inner-city neighborhoods is a financial challenge, Sonderman said.

“It’s a simple math equation,” he said. “The development cost is greater than what we can sell the home at, affordably.”

Even with volunteers and donated material, he said his construction costs have been about $250,000 per house. That’s $100,000 more than their sale price.

Behind that are 60-70 percent increases in construction costs over the last four years, Sonderman said.

Habitat has adapted by turning to smaller, 1,000-square-foot ranch homes.

“Many generations of families were raised in those houses,” he said, referencing the similar, post-World War II homes blanketing parts of metro Milwaukee.

“If we continue to build larger and larger homes, we’re not addressing the major housing shortage that exists in the community,” Sonderman said.

TID subsidy fills financing gap

But the $100,000 gap remains. Philanthropic donations pay for a chunk, Sonderman said. The TID subsidy covers about 40 percent.

When a city draws a TID around a construction site, it estimates the total property tax revenue the new development will generate for a number of years. That money can be used for improving surrounding infrastructure or paid to the developer upfront as a subsidy, with future taxes reimbursing the city’s expense.

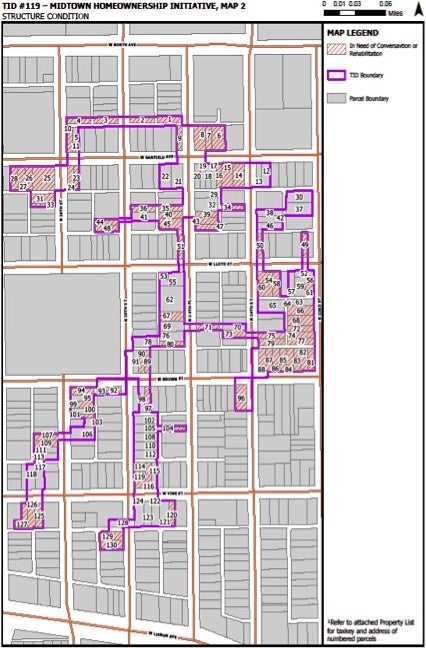

Because of the new TID’s unusual shape, the 74 homes built within it will pay their own subsidy through their future property taxes.

“The TID is a creative solution,” Sonderman said.

Wisconsin municipalities are increasingly subsidizing new housing — affordable, workforce and market rate — with TIDs.

That’s according to Todd Taves, a municipal advisor for the firm Ehlers, which works with municipalities to make TIDs across the state.

“It’s rare, from what I’ve seen, for an affordable or workforce housing project to get done without some sort of a TIF element in it,” he said, using the acronym for tax incremental financing.

For Stamper, the 74 new affordable homes are an encouraging step toward his biggest legislative priority: growing homeownership in his district.

“It’s the No. 1 way to prevent crime. It’s the No. 1 way for safety, and it’s the No. 1 way to build wealth,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.