A Dane County judge could decide as soon as Tuesday whether to allow voters with disabilities to receive and mark ballots electronically from their homes to vote.

Disability Rights Wisconsin, the League of Women Voters of Wisconsin and four voters with disabilities filed the initial lawsuit against the Wisconsin Elections Commission in April.

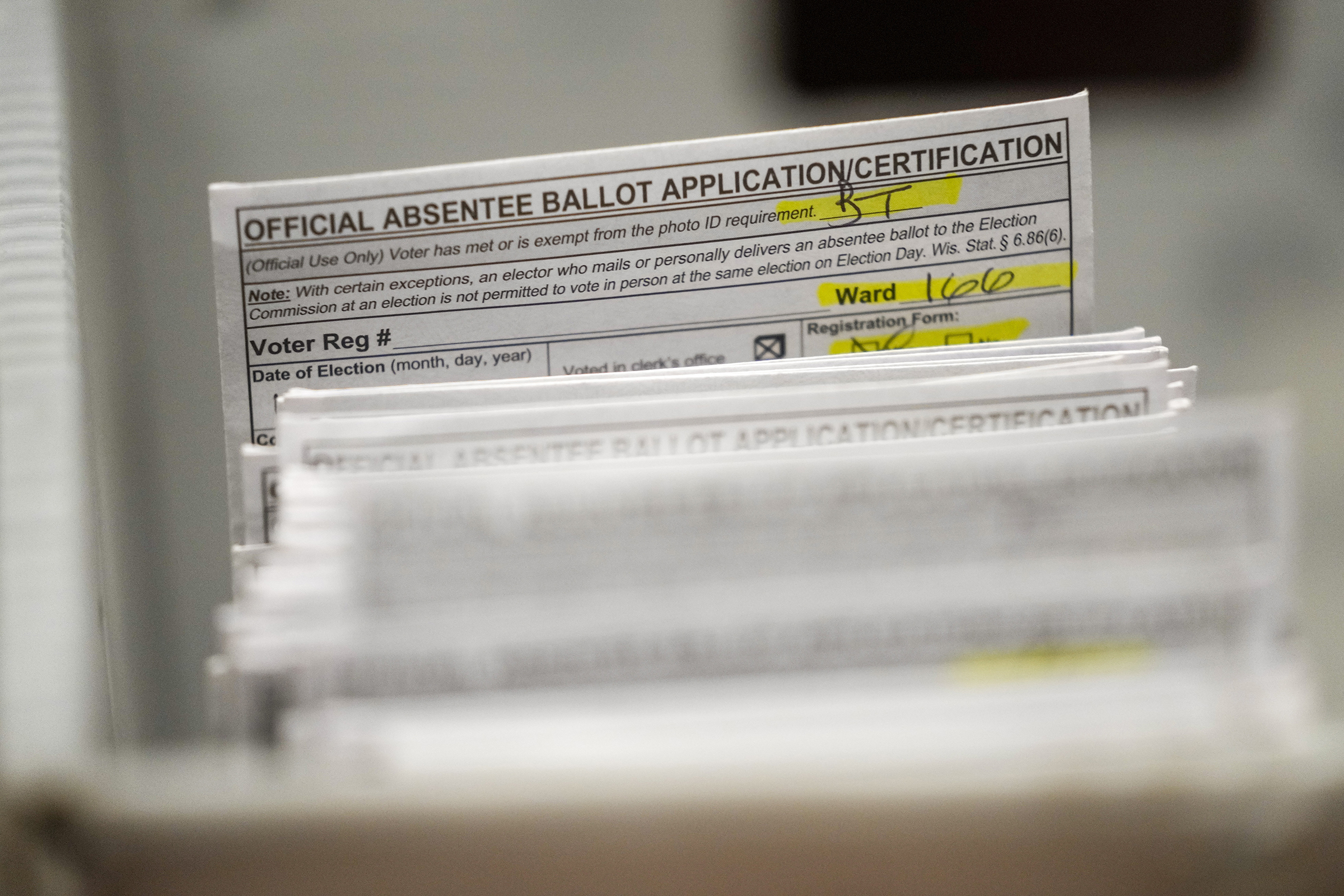

Before Monday’s hearings, the plaintiffs narrowed the lawsuit to first apply to absentee ballots for the November election but not the August primary. Ballots have already been drafted for August.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The injunction sought by the plaintiffs defines voters with a print disability as “a disability that prevents the certifying absent elector from being able to independently read and/or mark a paper absentee ballot, including blindness or a physical disability that impairs manual dexterity.”

It asks that qualified voters be able to receive, read and mark a ballot with the use of a screen reader. It does not ask for marked absentee ballots to be returned electronically.

Deployed military and people living abroad can already receive their ballots in Wisconsin elections via email or online. The lawsuit asks the court to allow voters with disabilities to do the same, in order to comply with state and federal laws ensuring equal access and accommodations.

Attorney Erin Deeley argued the U.S. Constitution guarantees the right to vote in secrecy and privacy.

“And there’s good reason for this right. It protects our democracy, removes risks of intimidation, ridicule, bribery and other corrupt, anti-democratic pressures,” she said.

Deeley said that one of the plaintiffs, Stacy Ellingen of Oshkosh, relies on a caregiver to fulfill her basic needs. Because of caregiver shortages, Ellingen often does not know her caregivers well, Deeley said.

“Voters should not have to demonstrate why they seek vindication of their right to a secret ballot. But Miss Ellingen understandably prefers not to disclose the content of her vote to her caregivers and cannot afford to compromise that care over feared political disagreement,” Deeley said.

No Wisconsin ballots are returned electronically, according to the WEC.

Military voters and those who are overseas permanently can either download their ballots from an online portal or have it emailed to them by a municipal clerk. Temporarily overseas voters can have a ballot emailed to them.

Not all clerks have access to the technology that would allow a ballot to be marked electronically, lawyers for the commission said.

WEC Administrator Meagan Wolfe testified in a deposition that it would take three months to develop, approve and provide training to nearly 2,000 county and municipal clerks.

Attorneys for the Elections Commission said ballots for the November election need to be approved by the end of August, which they argued is not enough time to implement the changes being sought in lawsuit.

Assistant Attorney General Karla Keckhaver said voters with disabilities already have the right to a secret ballot.

“When a voter uses an assistant, the elector’s vote is shared with one person confidentially. And that person is subject to criminal penalties if they reveal the vote to anybody,” Kerkhaver said.

“The voter is not required to vote in an open setting or otherwise disclose their vote publicly, which is what secret ballot is in contrast to,” she continued. “They’re simply voting a secret ballot with assistance.”

Wisconsin municipalities previously distributed electronic absentee ballots to anyone who requested one, the lawsuit says, until a 2011 law restricted that option to only deployed military and those permanently overseas.

A federal judge found the law violated the First and 14th Amendments, but that was overturned on appeal. The lawsuit argues that case “did not specifically address the unequal treatment and burdens faced by Wisconsin voters with disabilities.”

In 2022, the Elections Commission voted to tell local clerks they must allow disabled voters to request help from someone else to return their absentee ballots.

Absentee ballots have been a point of contention in the state, where four of the past six presidential elections were decided by less than a percentage point. The Wisconsin Supreme Court is reconsidering its own ruling limiting the use of absentee ballot drop boxes.

People with disabilities make up about 23 percent of Wisconsin’s population, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.