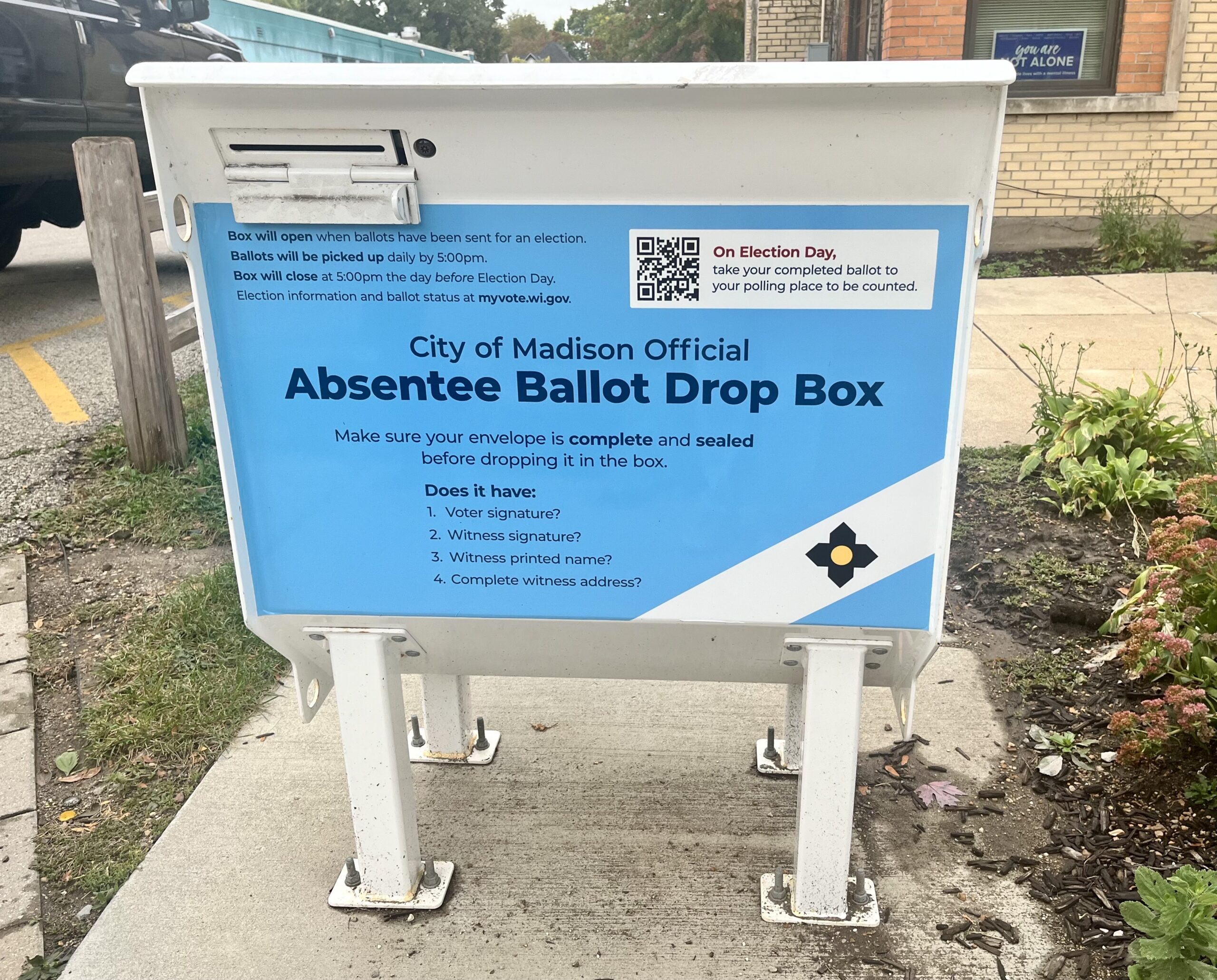

Voters can’t escape ads for the Wisconsin Supreme Court race on April 1, but the same election will also decide whether a voter ID requirement should be enshrined in the state constitution.

We know more now about how the requirement affects voting than we did when it was passed as a law 14 years ago. The arguments, however, have barely changed.

In 2011, Republicans were in their first session of single-party control of state government, and a voter ID law was near the top of their priority list. A previous governor, Democrat Jim Doyle, had vetoed voter ID bills. Now, Republican Gov. Scott Walker was poised to sign one.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“We’re going to make sure that everyone who’s entitled to a ballot gets one,” said then-Rep. Jeff Stone, a Republican from Greendale. “And that we know who the people are that are getting a ballot.”

The debate over voter ID did not happen in a vacuum. It was one of a series of bills Republicans took up that year that Democrats feared could tilt the electoral playing field to the GOP.

“This is not a voter protection act, but a voter prevention measure,” said Democratic Rep. Donna Seidel of Wausau. “It’s pure politics, plain and simple.”

In the state Assembly that day, Democrats argued a voter ID law would drive down turnout, particularly among Black voters. Republicans countered that requiring IDs would prevent voter fraud, and that the option for free IDs would make sure everyone could get one.

In the state Assembly this January, when the Legislature was debating whether to make voter ID a constitutional amendment, the circumstances and faces were different, but many of the arguments were familiar.

“Showing a photo ID to prove you are who you say you are establishes trust,” said Rep. William Penterman, a Republican from Hustisford.

“It is a transparent effort to preserve political power for one party and to give an advantage at the ballot box,” argued Rep. Greta Neubauer, the Democratic minority leader from Racine.

While the way the parties talk about voter ID hasn’t changed much, what it’s like to live with the requirement is no longer just theoretical. It’s been in effect for every election starting in 2016.

Here’s a look at how some of the major arguments for and against the law have panned out.

Supporters say voter ID prevents fraud. The evidence is sparse.

Before voter ID became law in Wisconsin, it was a rallying cry for the Republican base, the kind whose mere mention would get loud cheers at political events like the annual state GOP convention.

At the core of that argument was that requiring a photo ID to vote would prevent voter fraud, the kind that some voters assumed without evidence was happening regularly among voters on the left.

But even years after it took effect, finding data to show voter ID works — or doesn’t work — is challenging.

Data maintained by the state’s court system on criminal charges shows that over the course of six years from 2018 to 2024, prosecutors brought a total of 158 “election fraud” charges. A review of the data by WPR shows about 25 percent of these charges were dismissed.

The term “election fraud” is broad, and refers generally to a section of Wisconsin law that prohibits everything from showing someone a marked ballot to destroying nominating petitions. The most common category of fraud — illegal voting — covers more than 40 percent of the charges. Legal experts say this is often how prosecutors charge felons who vote before they’ve completed their probation, parole or extended supervision.

The election fraud law that specifically bans someone from impersonating another voter has been charged a total of two times over six years, leading to a single conviction.

“I think all of the evidence on the ground around elections suggests that there hasn’t been much effect in terms of actually deterring crimes,” said Barry Burden, director of the Elections Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Fond du Lac County District Attorney Eric Toney, a Republican, supports the voter ID law. He’s charged a variety of election fraud cases unrelated to voter ID, including felons who voted illegally, people who tried to vote twice and people who registered using P.O. boxes instead of their home address.

Toney said the fact that district attorneys have not had to bring actions against clerks to enforce voter ID shows that the law has been widely accepted and is working. The law, he said, is about ensuring confidence in elections.

“One of the things they teach us in law school is that sometimes the appearance of impropriety can be worse than actual impropriety,” Toney said.

Burden said it’s hard to argue that voter confidence has increased in the age of voter ID when accusations of fraud are so widespread, even if evidence of fraud is sparse.

Opponents warned voter ID would hurt turnout. It’s been high in recent elections.

In 2016, turnout in Wisconsin’s presidential election seemed to confirm critics’ worst fears.

It was the first presidential election held under voter ID, and turnout, which typically hovered around 70 percent in Wisconsin, dipped down to 67 percent. Compared to the previous presidential election, this was a decline of more than 67,000 voters, or more than three times President Donald Trump’s Wisconsin margin of victory over Hillary Clinton.

There are Democrats who think voter ID was absolutely a factor in this drop-off. Burden isn’t so sure.

“Turnout rates in Wisconsin go up and down for all kinds of reasons,” Burden said.

Other variables were at play that year. Trump and Clinton were both especially unpopular in 2016, and polls leading up to the race suggested Wisconsin was all but certain to be carried by Clinton and not that competitive.

By 2020, turnout was up around 70 percent again. Last year, it jumped to about 73 percent of Wisconsin’s voting age population — top in the nation, according to an analysis by the University of Florida.

That’s not to say the law has affected all voters equally.

Opponents said voter ID would hit some groups disproportionately. They might have been right.

Critics warned that some people — like Black and Latino voters or voters with disabilities — could be hit harder than others.

Limited data suggests that was indeed the case in 2016. A survey of registered nonvoters in Dane and Milwaukee counties by two UW-Madison researchers found that about 10 percent of all nonvoters were deterred from voting because of the law. The study estimated that number could be as much as three times as high among Black voters.

But more people have IDs now than they did then. The state law that created voter ID also set up a process for people to apply for free, state-issued IDs from the state Division of Motor Vehicles if they need one. Since 2011, the DMV has issued nearly 1.5 million free ID cards for voting, according to stats the state Department of Transportation shared with WPR. That number includes people who’ve registered for a free ID more than once after their initial ID expired.

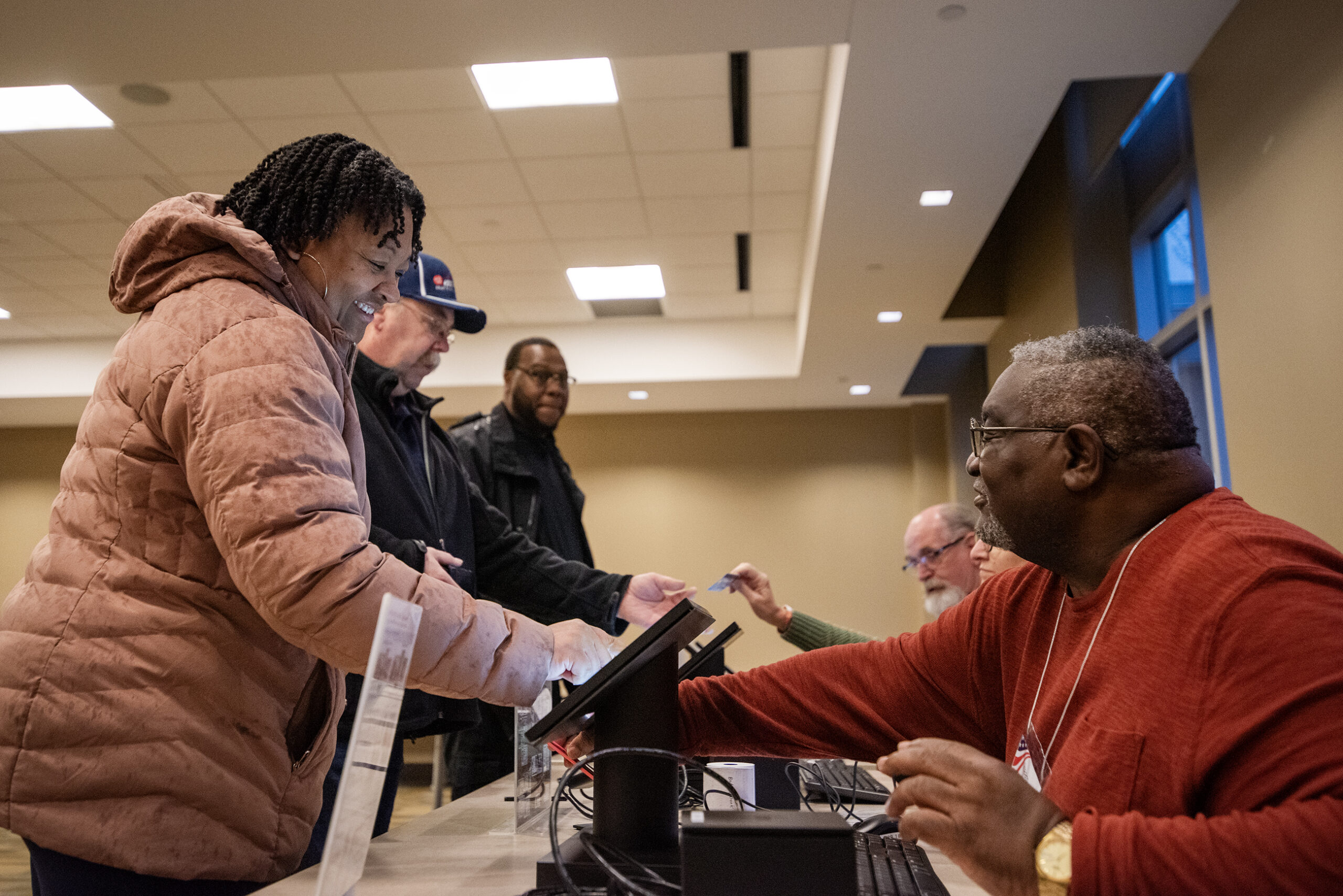

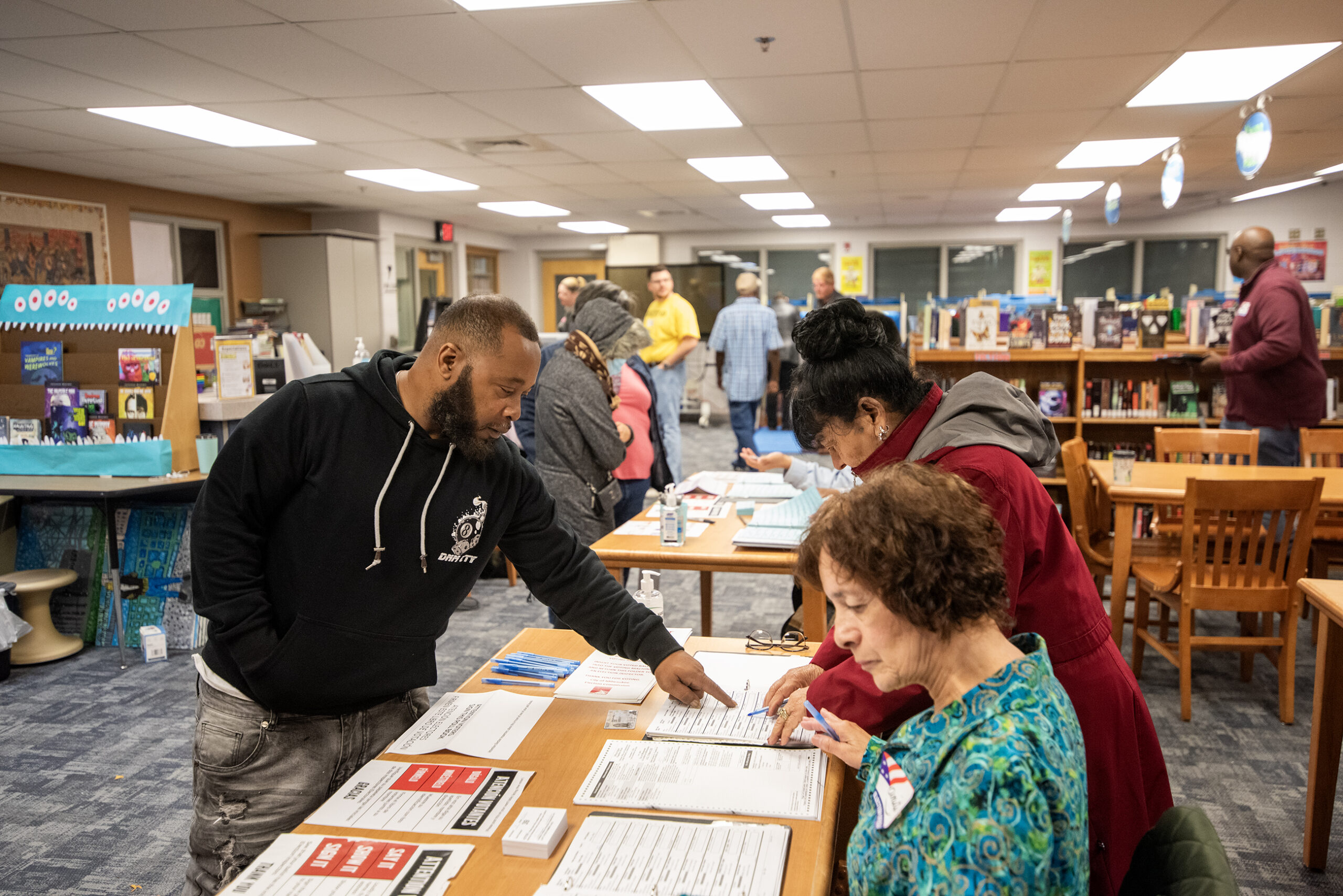

In practice, Anita Johnson said the voter ID law created a new challenge for some voters. Johnson is the outreach and voting specialist at Souls to the Polls, an organization that visits churches to encourage people to register to vote and help them with the process. She’s been doing this type of work for 25 years.

“There are a group of people who still don’t know — if I don’t have the money, I can go to the DMV and say, ‘I need an ID so I can vote,’” she told WPR. “So unless you sit down with a group of people and tell them, from A to Z, what you need to do in order to get that free ID, they still won’t know.”

Johnson said she has gone to the DMV with voters to help them navigate the process. She regularly visits churches and said she’ll go wherever she’s invited, but she primarily talks to people of color.

“Black and brown people, people with disabilities, the senior citizens — they’re all different types of groups that are suffering because of this photo ID or this voter ID law,” Johnson said.

Voter ID backers, and opponents, have pointed to the courts — but for different reasons

When opponents of voter ID argued against the law in 2011, they said the way it disproportionately burdened some voters made it unconstitutional.

“One thing you can be guaranteed,” said then-Minority Leader Peter Barca of Kenosha. “We will be back in court.”

As far as predictions go, this was low-hanging fruit. Big changes to voting laws are often subject to lawsuits. But few face as many challenges, or for as long, as voter ID.

Shortly after voter ID was passed, the Wisconsin League of Women Voters and the NAACP filed separate lawsuits in state court while the ACLU of Wisconsin challenged the law in federal court.

In March 2012, judges in both state cases issued orders that put the law on hold. A conservative majority on the Wisconsin Supreme Court eventually overturned their decisions.

But the law remained on hold because of the federal challenge until it was reinstated by the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago. It wouldn’t take effect again until 2016.

Another attempt to overturn voter ID appeared to come close that year, when the liberal group One Wisconsin Institute challenged a slew of voting laws Republicans had passed since taking control of state government. U.S. District Judge James Peterson overturned some of the restrictions, writing that “a preoccupation with mostly phantom election fraud leads to real incidents of disenfranchisement,” particularly among minority voters.

“To put it bluntly, Wisconsin’s strict version of voter ID law is a cure worse than the disease,” Peterson wrote.

But Peterson said he was bound to follow federal court precedent, and he upheld the bulk of the voter ID law.

The status quo appears unlikely to change soon in federal court, especially with a 6-3 majority of Republican nominees on the U.S. Supreme Court.

But in 2025, Republican backers of the proposed voter ID amendment are pointing to the state court system — and the Wisconsin Supreme Court — as a reason to enshrine the law in the state constitution. The court flipped to a liberal majority in 2023, and while there are no voter ID cases currently pending, Republicans say other rulings show justices are willing to revisit settled law.

“Having voter ID in the constitution will keep it safe from activist courts,” said Rep. Dave Murphy, a Republican from Greenville, in January.

The ideological balance of the court will be up for grabs in the upcoming election, and while it could potentially flip back to conservatives, there are Wisconsin Supreme Court elections on the ballot every year through 2030.

If the voter ID referendum fails, the issue could potentially be challenged again down the road. If the referendum passes, the long-running fight over this voting rule could be over, and voter ID could be the law of the land in Wisconsin for generations to come.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.