For thousands of years, people in what’s now Wisconsin used fire and stone tools to fell and split trees. They hacked away excess limbs and hollowed out the center to make dugout boats.

Today, two of those ancient canoes are sitting in a Madison warehouse, bathing in a preservative.

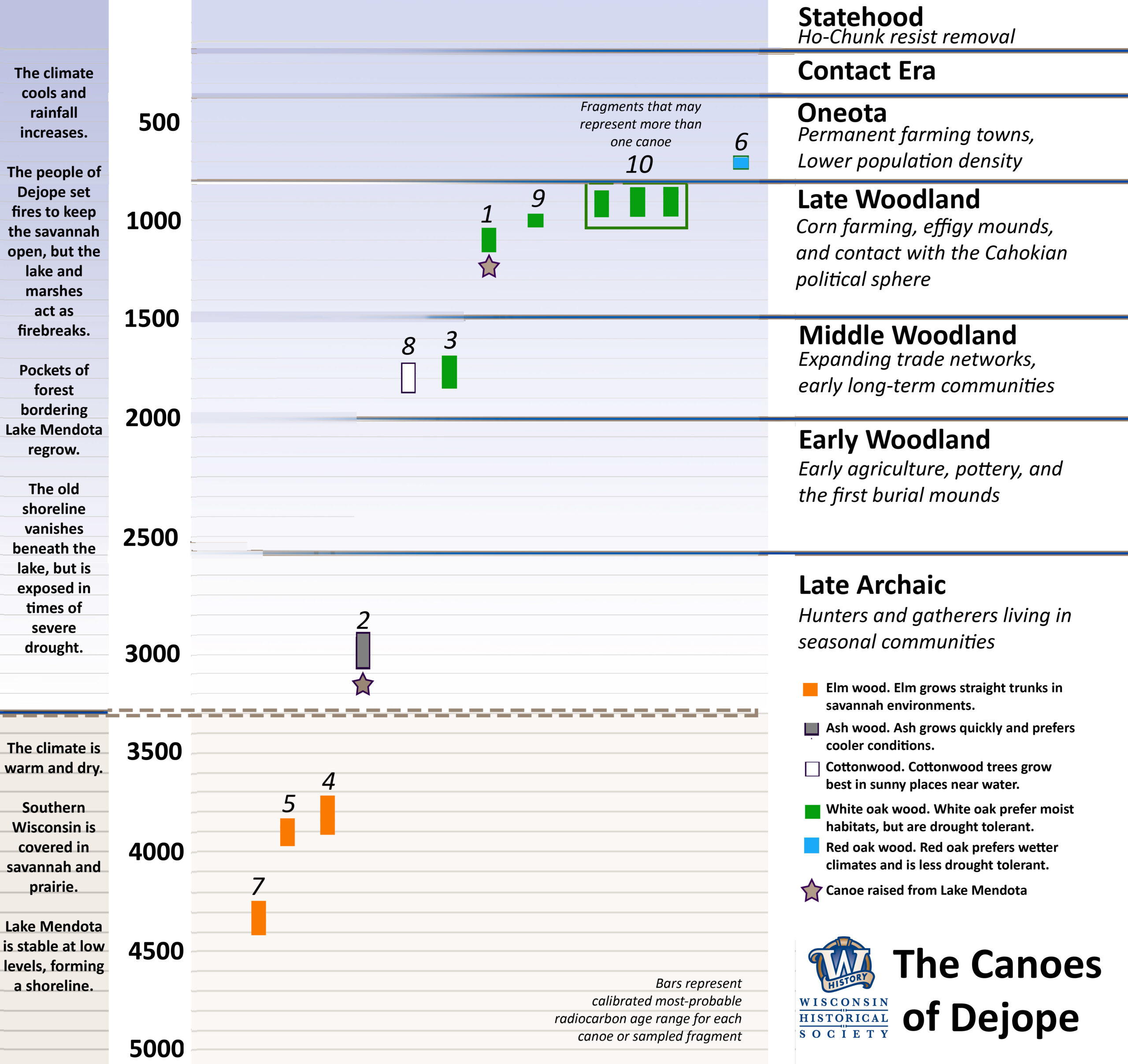

One of the unearthed canoes is 1,200 years old. The oldest is more than twice as old as that, dating back 3,000 years.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

They’re part of an underwater treasure trove, which was recently discovered submerged at the bottom of Madison’s Lake Mendota.

In all, Wisconsin archeologists say they’ve identified pieces from as many as 11 canoes, all found at the same stretch of lakebed.

The dugout boats are among the oldest ever discovered in North America. But archeologists are hopeful the canoe cache could be just the start of Lake Mendota’s story.

They’re continuing to study the boats, as they look for clues about what life was like for the people who made them. And they’re scoping out the lakebed for more artifacts from what could have been the site of a millennia-old Indigenous village.

‘Once-in-a-career’ finding struck again

For Tamara Thomsen, a maritime archeologist for Wisconsin’s Historical Society, the journey to uncovering southern Wisconsin’s cache of canoes began three years ago, when she was diving in Lake Mendota on her day off.

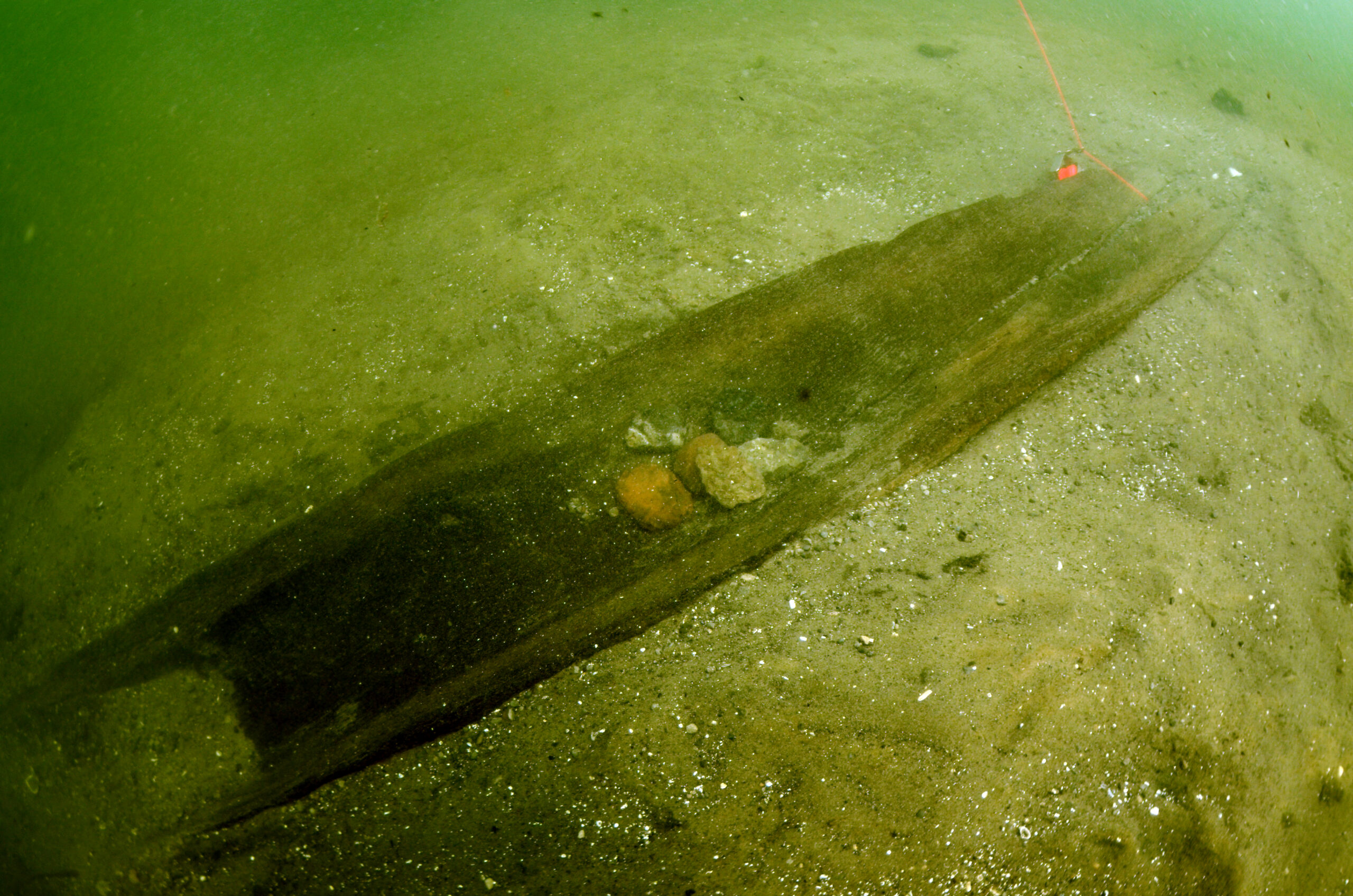

That’s when she glimpsed the end of a carved log sticking out from a sand shelf.

That log turned out to be the 1,200-year-old dugout vessel.

Amy Rosebrough, who’s now Wisconsin’s state archeologist, remembers watching anxiously from shore as a dive team dragged that waterlogged, but mostly intact, boat to land in 2021.

Algae limited the divers’ visibility to just a few inches while under water, and they moved slowly as they pulled the boat, which was 15 feet long, onto a scaffold.

Divers with the Dane County Sheriff’s Office swam alongside the boat to supervise the process, and Rosebrough knew that dropping the fragile vessel could be catastrophic.

When the team finally loaded the boat onto land, Rosebrough noticed a swell of noise from the beach, where a small group of onlookers had gathered.

“It actually scared me for a second because everyone was so on edge over the canoe and getting it up safely,” Rosebrough recalled. “Then I realized it was that crowd cheering and clapping.”

She remembers thinking, “This is something very, very special. I may not have another moment like this ever in my career. This may not be something that Madison ever sees again.”

But less than a year later, divers pulled a second, even older canoe from Lake Mendota after Thomsen spotted it in the same stretch of the inland lake.

At the time, that 3,000-year-old ashwood watercraft was the oldest boat ever discovered in the Great Lakes region.

That’s until this spring, when the historical society announced that fragments from as many as nine other canoes had been found along a span of about 800 feet.

The youngest canoe in the Mendota cache is 800 years old. The oldest was scooped out from elmwood 4,500 years ago — making it the oldest ever discovered in the Great Lakes region.

Florida still holds the record for the continent’s oldest dugout canoe discovery — that one is estimated at 8,000 years old.

Still, Wisconsin’s Lake Mendota canoe cache is a “world class” discovery, said Rick Torben, the curator of North American archeology at the Smithsonian’s Natural Museum of American History.

“It’s an amazing find,” Torben said. “Outside of Florida, I don’t know of any place in North America that has anywhere close to this concentration of preserved dugouts.”

Canoes span 4 millennia of Indigenous history

The Wisconsin Historical Society has been working with tribes, including the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin and the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, to identify and study the canoes, and Rosebrough describes the boats as part of the region’s pan-Indigenous history.

“They are so old, we cannot connect them securely to any specific tribes,” Rosebrough said, noting that the youngest canoes in the Mendota cluster are closer in time to the present-day than to the oldest boats found at the site. “They represent a shared Indigenous heritage of Wisconsin.”

For Bill Quackenbush, the Ho-Chunk Nation’s historic preservation officer, the canoes are a physical manifestation of Ho-Chunk oral history. That history describes the tribe’s presence in the area, known as Dejope, over multiple ice ages, since time immemorial.

“We didn’t survive thousands of years here,” Quackenbush said. “We thrived here for thousands of years.”

Why is one section of Lake Mendota yielding so many dugout canoes?

Wisconsin’s ancient canoes exemplify connections — not just across time, but also across geography, said Mike Dockry, an associate professor who specializes in Indigenous natural resources management at the University of Minnesota,

“I think a lot of times, in this day and age, we’re oriented towards the land, not the water,” Dockry said. “And I think we have to flip our mindset (and recognize) that those waterways were like our interstate highways.”

But why has one section of Lake Mendota yielded so many well-preserved dugouts?

One theory: Indigenous people returned to that spot over generations to stash their canoes at the edge the lakebed over the winter. They may have planned to return for those boats in the spring, but ended up losing some after they were buried too deeply by natural forces.

Another theory: Modern-day humans are altering the lake’s floor, as large boats turn around in that area, shifting sediment and exposing parts of long-hidden artifacts.

If so, Rosebrough wonders what else could be lurking in the rest of Lake Mendota, and in other lakes throughout southern Wisconsin.

“Are we talking about a bathtub ring of canoes all the way around Lake Mendota?” Rosebrough mused. “And, if that’s the case here, is that the case with Lake Monona, with Lake Koshkonong, with Lake Winnebago? Is this something you’d find it all of the lakes in Wisconsin?”

The Mendota canoes, Rosebrough says, are further evidence of a millennia-old Indigenous settlement. Remnants from that village could have become submerged as the lake’s levels shifted over time.

Rosebrough is training Thomsen to recognize clues, like rocks that were chipped by stone tool making. That way, Thomsen can look for those signs underwater when she’s out diving this fall.

“I didn’t think that these canoes would be as old as they were,” Rosebrough said. “So I’m not going to limit my dreams anymore. Maybe this will show us houses. Maybe this will show us storage pits or cache pits down there. And we can say, ‘OK, here’s the village. This is why there are canoes at this location.’”

2 canoes will be displayed at Wisconsin History Center

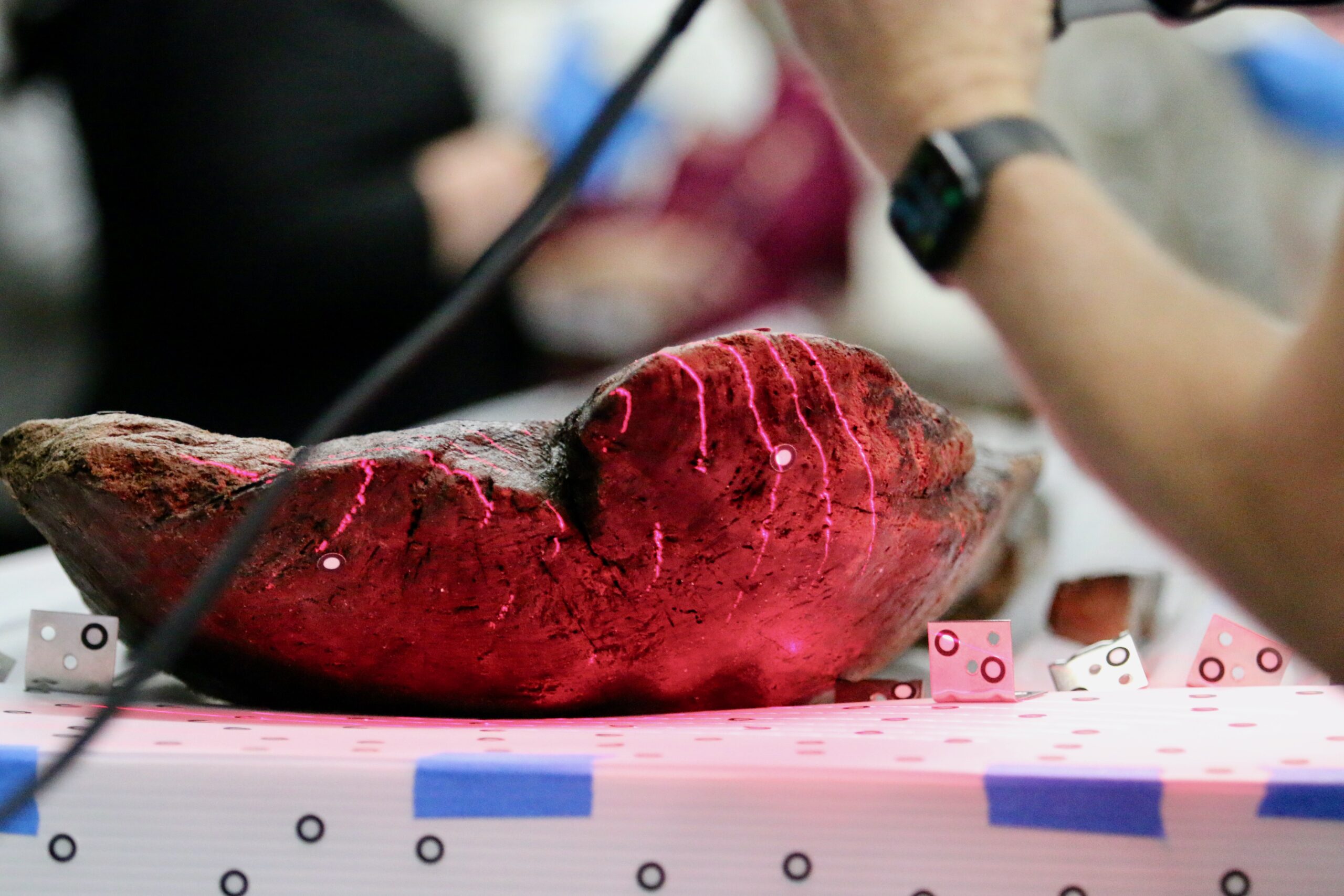

After years and years at the bottom of the lake, the canoes excavated in 2021 and 2022 took on the spongy texture of a sopping wet bagel.

Now, they’re ensconced in a custom-built vat at Wisconsin’s State Archive Preservation Facility. They’ll spend the next two years soaking in a waxy compound called polythene glycol to preserve their shape.

Eventually, the two boats will be freeze-dried, so they can be displayed at the Wisconsin History Center when it opens in 2027 near the state Capitol.

But state archaeologists believe the rest of the canoes at the Mendota site are too fragile to excavate. They’ll remain at rest under the water, while researchers try to learn more about them using non-invasive methods.

That includes working with Quackenbush of the Ho-Chunk Nation to map the depths of the lake with what’s known as ground-penetrating radar.

Over the winter, Quackenbush led the society on preliminary GPR mapping expeditions over the frozen lake. But that proved tricky during a historically warm winter.

So, the team settled on another idea. A few years ago, members of the Ho-Chunk Nation recreated a dugout canoe from cottonwood using a mix of ancient and modern methods.

Last month, Ho-Chunk members took that recently-constructed canoe on a weeklong voyage through sections of the Mississippi River. It’s part of a new tradition, in which paddlers take the dugout on a journey each summer through a different part of ancestral Ho-Chunk territory.

Now, Quackenbush and the state’s archeologists believe they’ll be able to shoot radar through the bottom of that new dugout using a GPR device.

“I think using this canoe, which is acting as an ambassador of sorts, to find its older brethren and to protect the site is just wonderful,” Rosebrough said.

Ancient canoes link Wisconsinites to our distant past

That sense of continuity may be part of why Wisconsinites are so passionate about the canoe discovery.

In 2022, onlookers once again lined the beach at Lake Mendota. This time, the crowd was larger than it had been a year before.

Once again, they cheered, clapped and prayed as divers pulled the hunk of carved wood to safety.

When Rosebrough gives presentations on Mendota’s canoe cache, some audience members tell her they feel close to weeping. It’s a sense of shared excitement that she hasn’t encountered previously.

“If I show somebody a spear point that’s 10,000 years old … they’ll think ‘That’s really interesting,’” Rosebrough said. “But they’ve never hunted a mastodon. They’ve never chipped a stone tool. They’ve never hunted with a spear and spear thrower. So it’s hard for them to make that connection.”

But just recently, Rosebrough was out kayaking on Lake Mendota. She shared the lake with motorboats, paddle boards and, yes, canoes.

“Suddenly it becomes real,” she said. “It’s people back then just like people today.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.