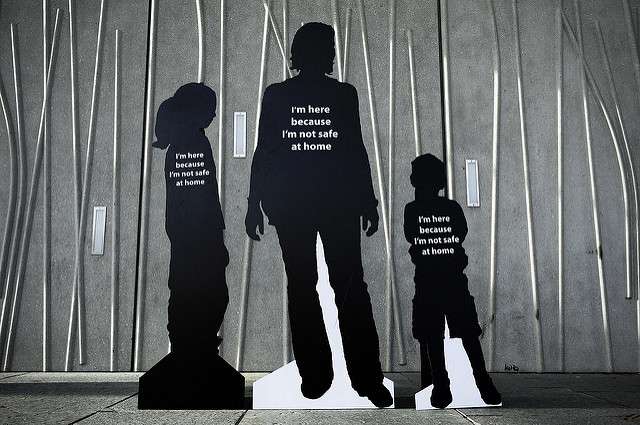

Kianna Hanson knows it can be terrifying for a victim of domestic abuse, harassment or stalking to come before a judge and ask for protection from their abuser.

“Oftentimes, these hearings are the first time that they’ve ever spoken about what they’ve been experiencing. And on top of that, they are sharing often, the most traumatic thing they’ve been through in a courtroom that’s open to the public,” said Hanson, who is the community advocacy manager for Domestic Abuse Intervention Services based in Madison.

It can be even more traumatic with their abuser present in the courtroom, Hanson added. But judges can help victims trust the system.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Just treating everybody in the courtroom with dignity and respect makes such a huge difference to a survivor,” Hanson recently told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

“We’ve had clients that have had their injunctions denied, so they haven’t been granted a long-term restraining order,” she said. “But even in those cases, when the judge takes the time to kind of call out the abusive behaviors and validate the survivor and say, ‘I’m sorry that this happened to you, please come back if anything else happens’ — that makes such a big difference.”

Domestic Abuse Intervention Services spent a year monitoring every request for an injunction in Dane County. Its report, released late last year, found that not every judge follows the law and some are perpetuating myths.

Hanson explained the findings to “Wisconsin Today.”

The following has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Kate Archer Kent: I was just struck by the sheer number of hearings that the research team sat in on, looking at over 800 cases. Can you explain how the court watch study worked?

Kianna Hanson: (Domestic Abuse Intervention Services) has court watch volunteers as well as staff who observe injunction hearings. Injunction hearings are what they call the long-term restraining order hearings. Our volunteers went through 26 hours of training to be prepared to know what to look for in the courtroom. And then they went through three hours of training where they learned about legal terminology, the different types of restraining orders and what that process looks like.

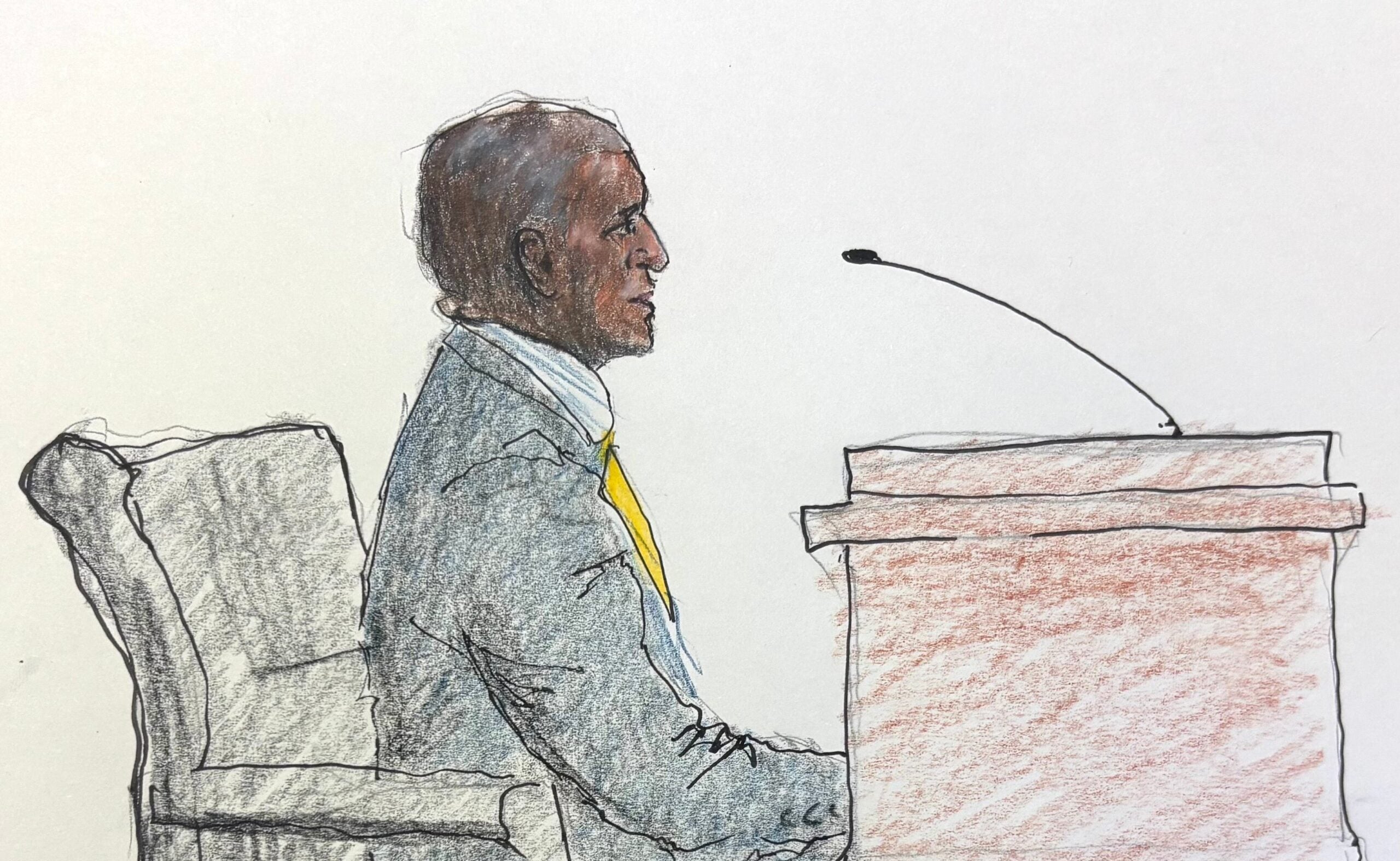

So our observers sat through all of the injunction hearings each day that they had them, and they collected notes on some of the demographic information, as well as more of that subjective data and tracking the judges comments and behaviors.

KAK: The report found judges granted restraining orders in 34 percent of the 814 cases that were observed. Should that percentage be higher?

KH: Our goal with the Court Watch report is not necessarily to advocate that they should be granting more restraining orders. It’s more about the trauma-informed practices and making sure that they are following all of the statutory requirements for restraining order hearings.

I think it’s important to note that 87 percent of petitioners who were seeking restraining orders appeared pro se, meaning that they did not have an attorney representing them. And our research found that petitioners that had attorney representation were 74 percent more likely to have their restraining order granted.

KAK: That is eye-opening, that representation by an attorney or a legal advocate vastly increases the chances of a restraining order being granted. What does that say about navigating our legal system?

KH: The legal system is really confusing. There’s all sorts of legal jargon that gets used, so kind of simplifying that process as much as possible is something that we advocate for.

KAK: The report notes that even when judges grant restraining orders, they sometimes perpetuate myths about intimate partner violence. One of those is this notion of a “cooling-off period.” Can you explain what that is?

KH: There consistently has been this notion of a judge deciding to grant an injunction for less time than the survivors asking for, and the reason that sometimes they will cite for doing so is this idea of the cooling-off period. A petitioner might ask for a four-year restraining order, and the judge might only grant a six-month restraining order.

Not only does that go against the Wisconsin statute for domestic abuse injunctions, it is a myth regarding domestic abuse. It perpetuates this idea that domestic violence is a result of somebody just being angry and not being able to control their emotions. But what we see is that domestic violence is most often a conscious choice, and it’s rooted in obtaining power and control over an intimate partner . . . So it’s really best to follow the survivor’s lead on how long they need this protection in place to be safe.

KAK: The organization is working on a follow up report that you expect to be released in the fall. What other data are you hoping to collect?

KH: We will be looking closer at firearms surrender hearings, seeing whether that follow through on making sure that firearms are kept out of people who have domestic abuse injunctions granted against them is happening.

Additionally, we are going to be taking a closer look at the disparities in the courtroom for people of color.

And then one final change that will be happening is that historically, DAIS has not named judges in the report. Moving forward, we will be associating the judges’ names with the comments and quotes that they have said. And we’ve made that decision based on consulting with our advisory group and from just feedback from the community about the importance of accountability and being transparent with what’s happening in the courtroom.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.