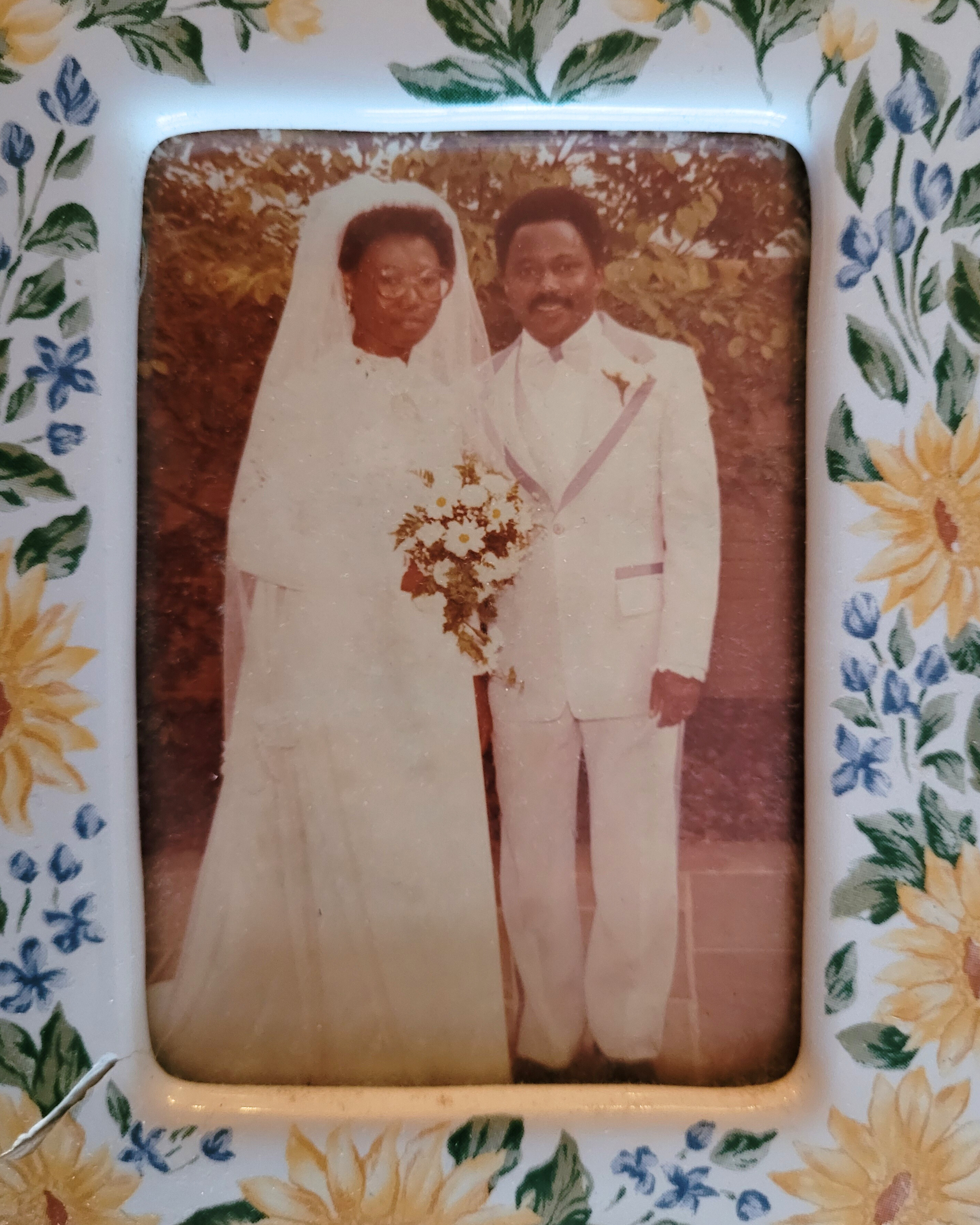

When Theresa Okokon was nine years old and growing up in Wisconsin, her father traveled to his hometown in Nigeria to attend his mother’s funeral.

He never returned.

“I don’t have any memory of my dad saying our last name. That’s not a thing that a 9 year old would commit to their memory, because a 9 year old is not going to think they need to remember the sound of their dad’s voice.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“They’re not going to think they need to remember the way their dad pronounced their last name,” she said when talking about uncertainty over what syllable to stress in her surname.

Okokon still remembers her mother’s “be-strong-for-the-kids” posture, when she heard about her father’s mysterious death. It shattered Okokon and changed her family’s trajectory. She, her mother, and three siblings navigated a world without him, without ever finding out exactly what happened.

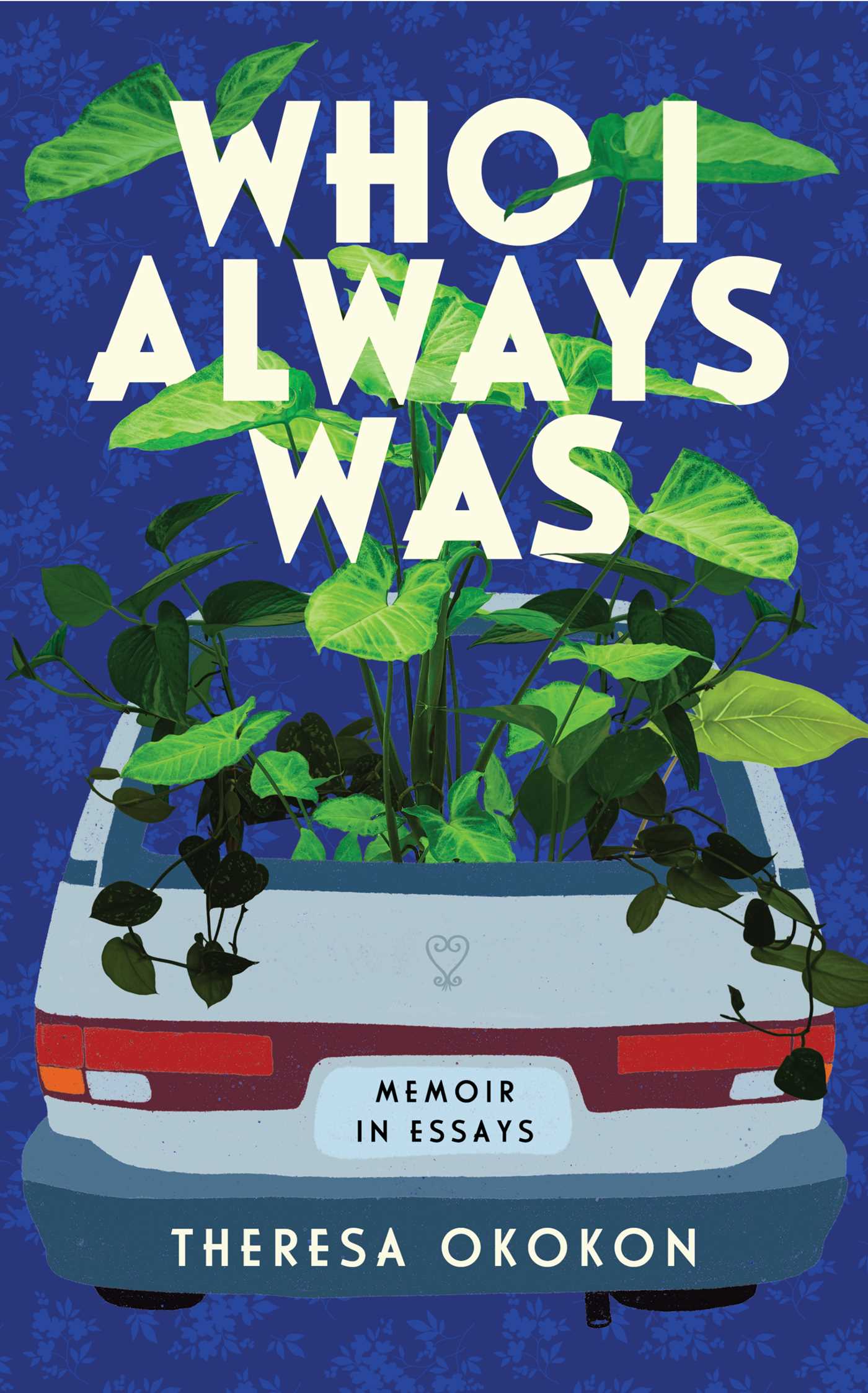

Okokon is a Pushcart Prize-nominated essayist and co-host of WGBH’s “Stories From The Stage.” And she’s out with a new memoir to explore that family loss, titled, “Who I Always Was.”

The book weaves together experiences growing up in nearly all-white communities and moving to the Mequon school district. And, when her kindergarten teacher refused to call her by the name her family used, Ini.

She talked with “Wisconsin Today” about the ripple effects of profound family loss and abandonment, themes of Blackness, and the unrequited romantic pursuits of a Black girl coming of age in Wisconsin.

The following interview was edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: Your parents immigrated to Wisconsin from Nigeria and Ghana, and met at Marquette. Your father disappeared when you were young but you only started to dig deeper into his death when you began writing this book in middle age. Why is that?

Theresa Okokon: I’m introspective and I’m just naturally drawn to understanding myself. But it occurred to me sometime in my late 20s, early 30s that I had fully accepted the amount of silence surrounding the story of how my dad died.

I remember once my writing mentor said, “Your dad dies on every page and you never tell us how.” And I realized that part of why I wasn’t telling the story of how he died is because there were so many variations of that story, that I was really struggling and grappling with.

Looking at his death through a cultural lens, there isn’t a way to just say, “Capital T Truth — this is what happened.”

So I came to a place where I was like, “If I’m really going to try to understand myself, I need to at least create a narrative about my dad’s life and about my dad’s death that I can accept.”

(Editor’s note: In the book, Okokon reveals a suspicion that a relative in Nigeria may have had something to do with her father’s death.)

KAK: As you go through your dating life, you come up with a standard line to discuss your dad’s death: “It’s OK, you didn’t kill him.” Is that a coping mechanism?

TO: If someone tells you that their dad died when they were 9 years old and then you say, “I’m so sorry,” and their response is, “It’s okay,” … it’s probably not.

That part of it was a coping mechanism. It was sort of like, “I don’t need you and you don’t need to feel bad, and don’t feel like you need to carry this burden for me by feeling sorry or sad about it.” Then the “you didn’t kill him” part, which I started saying as an angsty preteen and teenager, was intentionally provocative, trying to get people to stop asking questions about it.

There’s many times I’ve said that in my life and I don’t think anybody has ever responded with, “ Did someone kill him?”

KAK: When you enter kindergarten in River Falls, you are going by your middle name Ini, and your teacher Mrs. Wilson, is refusing to call you that. Can you share that story?

TO: Up until kindergarten I went by my middle name, which is Ini. It’s short for Ini-Obong, which means “God’s clock” or “God’s time.” And that’s what everyone called me.

And on the first day of kindergarten, my mom would have registered me as Theresa. But when I introduced myself to my kindergarten teacher, I introduced myself as Ini. And my kindergarten teacher just flat out refused to call me that.

What I was always told is that she said, “Does she have a real name? Does she have an American name that we can call her?”

So that’s how I started going by Theresa, because my mom was like, “Well, I guess you can call her Theresa.” I knew it was my name but I didn’t know to respond to it. And I was not the only kid in my kindergarten classroom who experienced that. There was another student of Asian descent who also experienced the same thing. And both of us continue to go by the name that we gave to Mrs. Wilson instead.

KAK: When you’re a senior in high school, your mom built a house in Milwaukee County without a room for you. At the time you’re obviously hurt and angry, but as an adult you see this situation differently. What was it like to address this memory and then see it from your mother’s perspective?

TO: I don’t know that I took the time to see it from my mom’s perspective until I started writing about it. And there are a lot of things about understanding my mom and what it was like for her throughout our childhood that, as an adult, I eventually start to put some perspective on.

So we had been living in Mequon and the story of her building this house in Milwaukee that didn’t have a room for me was really one that I was continuing to hold onto a lot of anger and a lot of angst about, until I sat down to write about it.

I had to realize that my narrator wasn’t reflecting on what it was like for the other characters in the story and was really only approaching the story through how my “I” character saw it, to speak about this from a writing craft perspective.

That’s part of the work of writing a memoir. If you think that you’re going to just write from your own perspective and that you’re only going to be telling your “Capital T Truth,” you’re wrong. You should realize that what you see as the truth will evolve in the process of writing a memoir. And that was certainly my experience.

To recognize that my mom was and is a human, that she’s not just my mom, means that sometimes she is making choices that make sense for her and it’s just not about me — it’s not about my sisters, it’s not about my brother. As a kid you don’t really recognize that about your parents.

KAK: As a reader, I just feel heartbroken when she loses the house. After all the work and everything she’s done to hold the family together, she becomes a renter and you have to go through all the discarded items from childhood to try to condense her life as well. Can you talk about that moment?

TO: One of the things that that house had that really mattered to my mom was a garden. It had a garden in the backyard. And my mom loves gardening. She would plant vegetables and I remember she grew very tiny strawberries that were very sweet, but they were her strawberries. It was hers, that was her home, the first home she had built for herself and it mattered.

When she lost that house — from my perspective, in response to the housing crisis when people were being given loans that they probably couldn’t actually afford — it was devastating. It was devastating for her. It was devastating for our family. Even though, for me personally, that house never really felt like it was my house. It very much felt like it was my mom’s house. But it was devastating to witness her lose it.