When Ken Brosky heard the news last year that the Waukesha branch campus of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee was slated to close in 2025, he realized it was a “wake-up call.”

The Waukesha campus “was always seen as one of the crown jewels of the two-year UW colleges, and for it to close was just so shocking to me,” Brosky told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

“I wanted to start digging into what was going on,” he added.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Brosky, a professor of creative writing at UW-Whitewater at Rock County, decided to start documenting the closure of two-year campuses in the Universities of Wisconsin system.

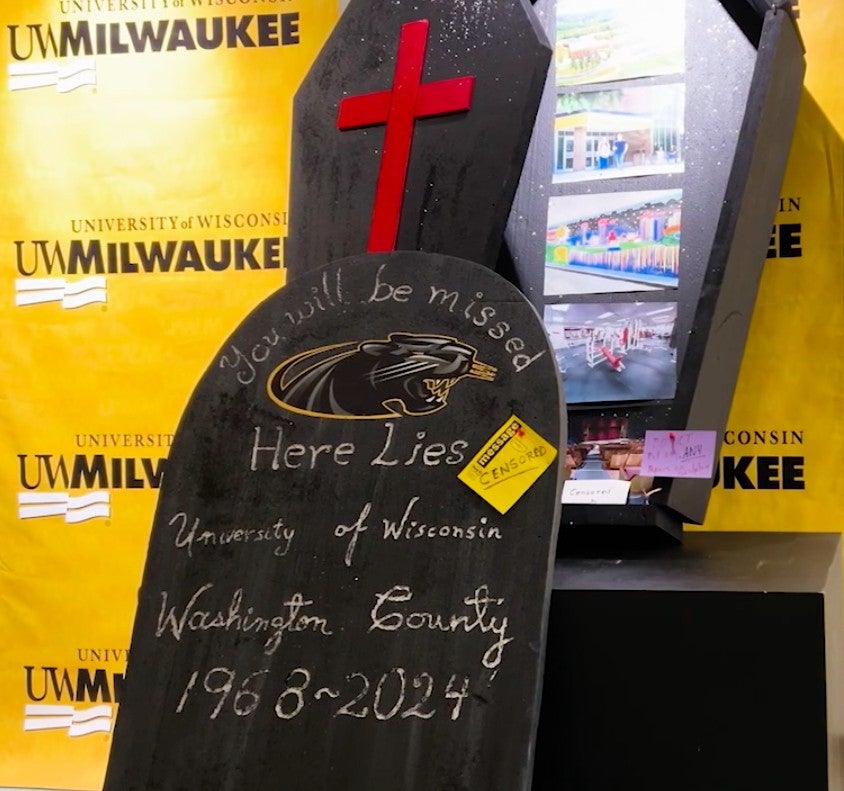

With a video camera and a $3,000 budget crowdsourced on Kickstarter, he visited two campuses that were in the process of shutting down last summer: UW-Milwaukee at Washington County, which was holding its final classes, and UW-Platteville Richland, where UW was vacating the campus after local officials spent a year fighting to keep it open.

From 75 hours of footage and interviews, Brosky created “Closure: The Dismantling of Wisconsin’s Colleges,” an 87-minute documentary that has screened at libraries and campuses around the state, including the Door County Film Festival.

Brosky said he had no training in filmmaking before this project — he shot and edited the documentary with skills he picked up along the way because he was committed to telling the story.

The film looks at how UW’s two-year colleges went from being a valued part of the state’s public university system to being shut down or at threat of closing. While university administrators and state lawmakers often cite declining enrollment as a reason for downsizing or closing campuses, Brosky doesn’t believe this was inevitable. He blames the closures on budget cuts under former Gov. Scott Walker and then the restructuring of the university system in 2017, which merged two-year colleges with four-year UW schools.

Since the restructuring, six two-year colleges have closed or will close this year, while seven remain as “branch campuses” affiliated with a four-year university.

The film situates this restructuring as the beginning of the end for the two-year campuses. Now under the umbrella of a larger institution, colleges like Richland found their efforts at outreach and recruitment being undermined as students were funneled to four-year campuses.

For example, Brosky said the Richland County Board proposed funding a full-time recruitment officer for its two-year campus, now affiliated with UW-Platteville, but the offer was declined.

“It’s like a snake eating its tail,” Brosky said.

On top of that, Brosky believes that the two-year campuses have value that goes beyond a simple ledger.

“People just say, ‘Oh well, nobody wanted to go to these colleges’ or ‘Oh well, enrollment is down, and you’ve got to cut spending because it’s wasteful,’” he said. “But I don’t know, is it really wasteful? I just don’t buy it.”

The documentary is free to watch below in full on YouTube.

Two-year colleges are havens of student support and community outreach, filmmaker says

Marnie Dresser taught at UW’s Richland campus from 1992 until it officially closed last year. She spoke with Brosky for the film while she was packing up her office.

Dresser recalled a time when she encouraged one of her students, a promising young writer, to apply for the creative writing program at UW-Madison after getting her associate degree at Richland. The student said she would love to go to Madison next but was nervous about jumping headfirst into a big program on a campus that was unfamiliar to her.

“I said, ‘You know what, how about I drive us to Madison and I take you to where you would take creative writing classes and introduce you?’” Dresser recalled in the film.

Visiting the campus with Dresser and meeting the creative writing faculty calmed the student’s nerves, and she ended up earning a bachelor’s degree from UW-Madison.

That personalized attention and commitment to student success is common at the two-year colleges, Brosky said.

“I don’t know how to quantify this for people who are looking for a spreadsheet cost-benefit analysis of these campuses, but for a lot of professors and a lot of faculty and even part-time teachers on these campuses, this was the norm,” he said. “Because we treat education like a business … it’s very hard to defend keeping these campuses open because how do we quantify that kind of outreach?”

The two-year campuses also serve as hubs for the small towns where they are located, Brosky explained. UW colleges regularly put on concerts, science fairs and museum exhibitions that are free for community members to attend. His campus, UW-Whitewater at Rock County in Janesville, is hosting a local high school theater production this year.

The two-year campuses also create an affordable option for local high school graduates to get their associate degree, which can prepare them for further college education or the workforce.

Brosky said that recruitment is the key to attracting students who don’t see themselves as “college material.”

“What a lot of people don’t understand is the two-year colleges, what they do well is they go out and they find students who weren’t necessarily thinking about college and give them an affordable place where they can start,” Brosky said.

A Wisconsin Idea success story

Troy Winkelman considers himself “a bit of a late bloomer.” He didn’t earn stellar grades during his first couple years of high school, so even though he began to find his stride during junior year, his GPA didn’t qualify him for many scholarships.

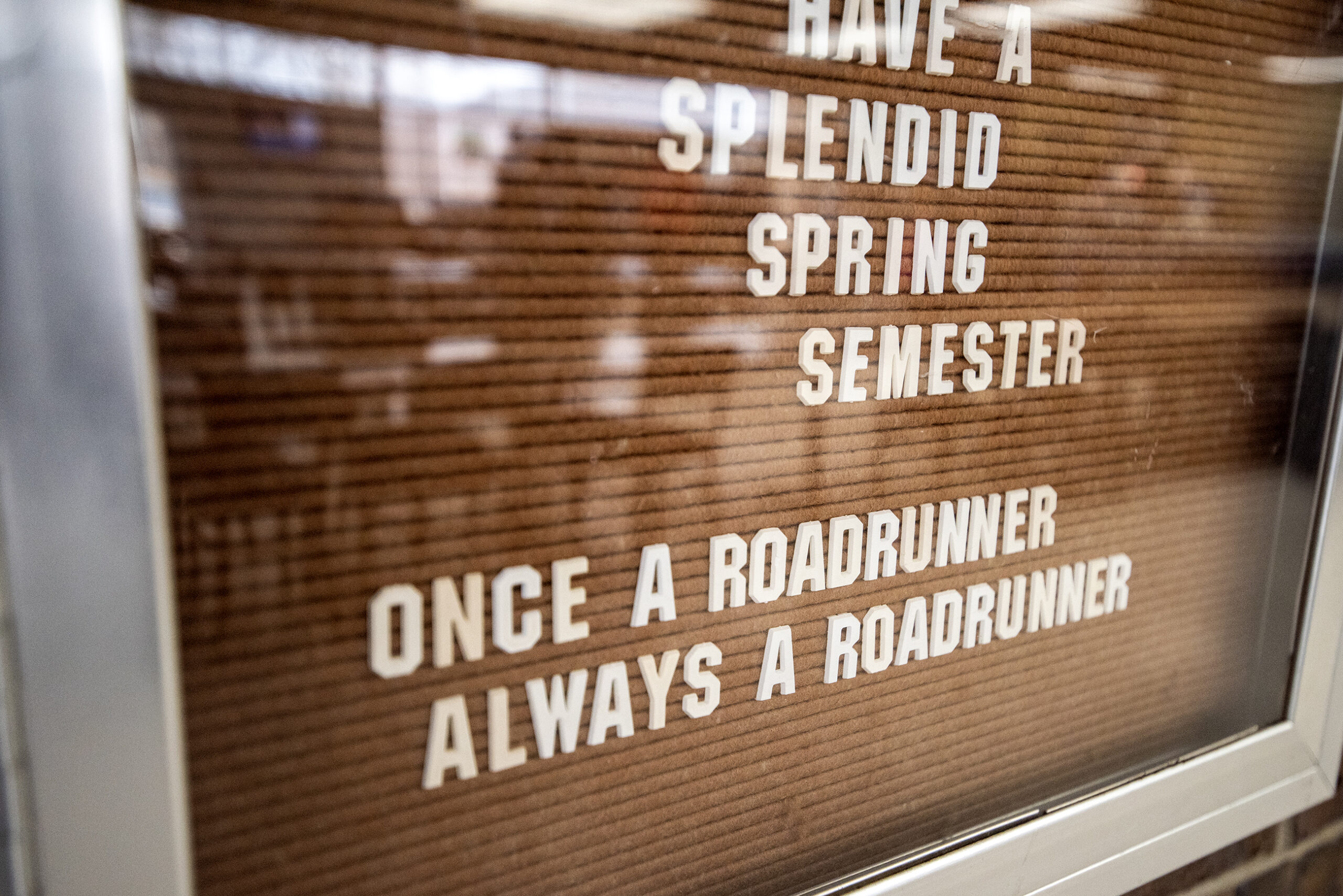

With the help of a high-school advisor and his mom, Winkelman enrolled at his local two-year college, UW-Washington County, which was the name of the campus before it integrated with UW-Milwaukee.

Winkelman, who is autistic, told “Wisconsin Today” that Washington County was a great place for him to start his college education because he was able to get the extra attention he needed to get through his general-education requirements. While there, he also played basketball, tennis and soccer and served in student government.

“For a kid who came in very bright-eyed and bushy-tailed but not very well-rounded as a leader … I left there ready for the next step, ready for leadership roles, ready for a four-year college and ready for the real world,” Winkelman said. “I think that if I would have gone to a four-year college [right away], I would have gotten lost in the shuffle.”

In 2009, Winkelman graduated with his associate degree debt-free because tuition was low enough that he could pay for it out-of-pocket with a factory job. He was also able to fund a study abroad trip to Europe.

Now a graduate of UW-Oshkosh, Winkelman lives in Oshkosh with his wife and three kids. He has a stable career, which he credits to his liberal arts education.

“The amount of value that I got from the University of Wisconsin-Washington County is greater than any check for tuition that I ever wrote,” he said.

Winkelman said he was “floored” when he learned about the closure of his old campus. He is angry that future generations of students won’t have the same opportunities he did.

“The biggest part of the Wisconsin Idea is an accessible and affordable education,” he said. “How in the world do you make education more affordable when you close the most affordable school that the UW system has to offer?”

“Closure” is screening at UW-Stevens Point on April 8. More information about the documentary is available at DelavanFilms.com.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.