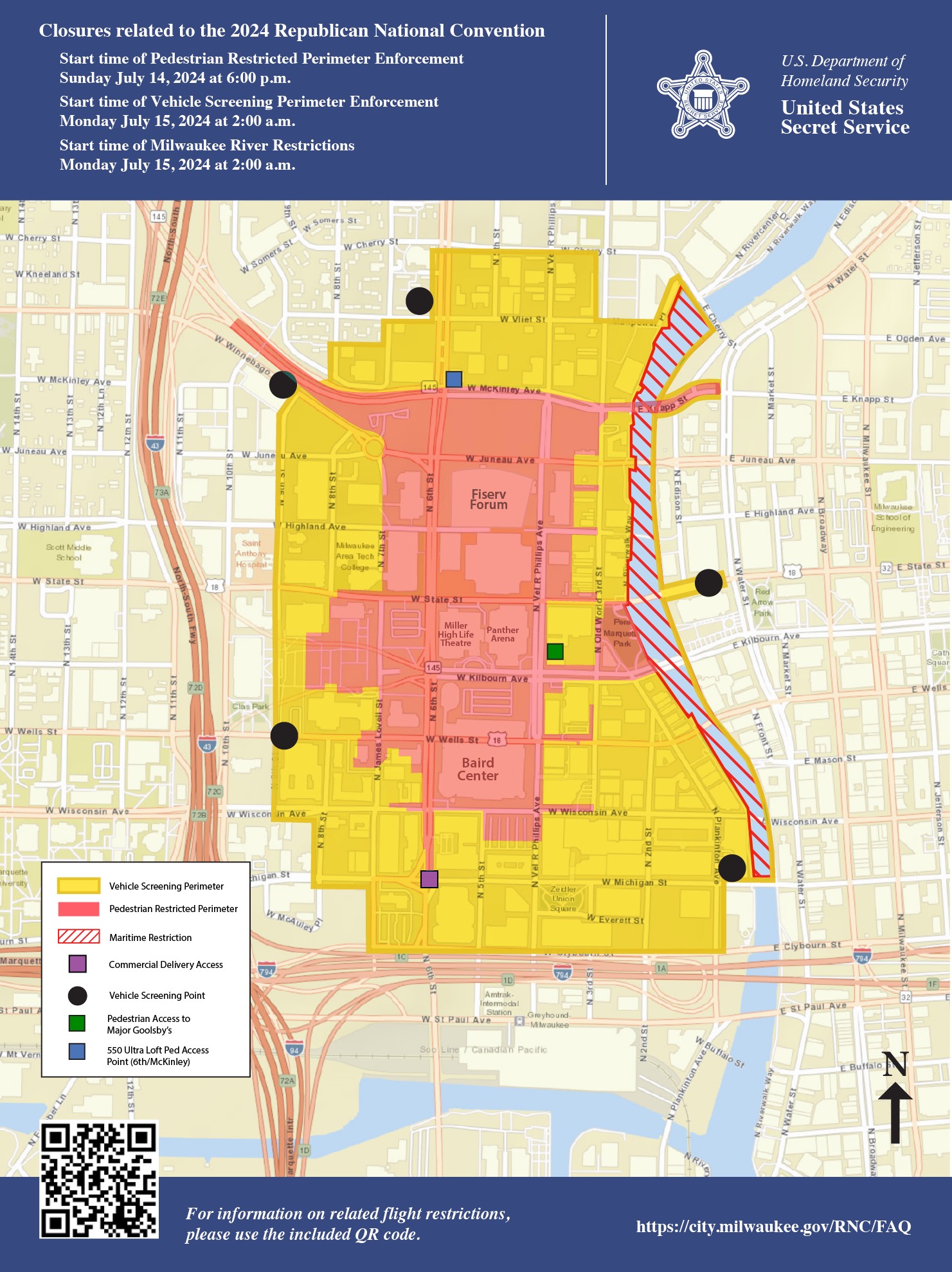

The city of Milwaukee and the U.S. Secret Service announced their security plans last week for the upcoming Republican National Convention, which includes designated zones where protestors will be allowed to demonstrate.

The American Civil Liberties Union filed a federal lawsuit against the city on behalf of protest groups, arguing those restrictions violate their First Amendment rights of free speech and assembly.

The two sides unsuccessfully tried to mediate the case, which now continues through the federal court system with the RNC less than three weeks away.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Howard Schweber, an emeritus professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, thinks the judge still has enough time to rule on this case, which he expects will be in favor of the city of Milwaukee.

Schweber spoke to WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” about the First Amendment arguments in the case and the lack of clearly defined legal guidelines on the issue.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: What stands out to you about the details of this free speech dispute?

Howard Schweber: The law requires that you have rules about what’s called the time, place and manner of public expression that preserve order and safety but that leave an adequate avenue for expression. The rules can’t be such a nature that effectively they silence protest. The protesters are claiming that’s what’s happening here, and that claim has been made in lots of other places.

An effective protest has to be disruptive, at least to the extent of getting people’s attention and distracting them from what’s going on. So there really are two opposing fundamental goals here, and the courts have never resolved the question. They’ve never established when or how these kinds of free speech zones are permissible or when they go too far in isolating protesters from their intended audience.

KAK: Is there a legal definition for what constitutes the protestors being within “sight and sound” of the major venues for the RNC?

HS: The guidelines are vague. There must be adequate channels of communication. But what constitutes an “adequate” channel is entirely in the eye of the beholder, which is why this has become the strategy of choice.

College campuses are also using this strategy. This is a growing and pervasive tactic to tamp down protests, and as a result, it’s become a growing and pervasive issue for First Amendment law that the courts have not at all resolved.

KAK: What is the burden that the ACLU and the protest groups will have to prove in court to win a suit like this?

HS: They will have to prove that the designation of zones and routes for protests does not provide them with adequate channels of communication, and what they’ll have to do is make some kind of argument about what an adequate channel would look like and why these are not adequate. The city’s burden will be to respond and argue that what’s being provided is adequate, but also to demonstrate some real basis for concern of disruption and security issues, which I think they can probably provide.

It’s all kind of hypothetical and speculative. Based on the record of cases thus far, I expect the federal court to side with the RNC. Courts have been deferential to concerns about order and security when they’re brought by cities or major national organizations. And frankly, our courts are very protective of certain First Amendment rights, particularly religious freedoms these days, but not particularly protective of the rights of protesters to be heard.

KAK: Is there still enough time for a federal court to work through a case like this, with the RNC less than a month away?

HS: Federal courts are able to move quite quickly and quite nimbly. This is plenty of time to reach a resolution, and it’s plenty of time for the City of Milwaukee to respond to whatever order the court issues.

The worst outcome, in some ways, would be if the judge allows the matter to drag on, and then says, “Well, we’re stuck with what we have because it’s too late to ask Milwaukee to change anything.” That would leave all questions unresolved and all parties unsatisfied.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.