As the cook of the family, Jim Boisen of French Island used to love making big batches of soup and freezing them to use throughout the year. But when he learned that his homemade soup reserves were filled with tap water containing harmful PFAS chemicals, he felt he had no choice but to throw them out.

“I put a tarp out on the driveway and dumped them all right out. I said, ‘There’s my soup.’ That’s what PFAS did for us,” he told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “I don’t make soup anymore because of that.”

Boisen and his wife, Margie Walker, moved into their home in the town of Campbell on French Island after getting married in 1979. The island sits a few miles north of La Crosse, surrounded by the Mississippi River, Lake Onalaska and Black River. For Boisen, it was a kind of “paradise,” especially when he was able to go out fishing — another hobby he gave up after learning about PFAS in the area more than four years ago.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

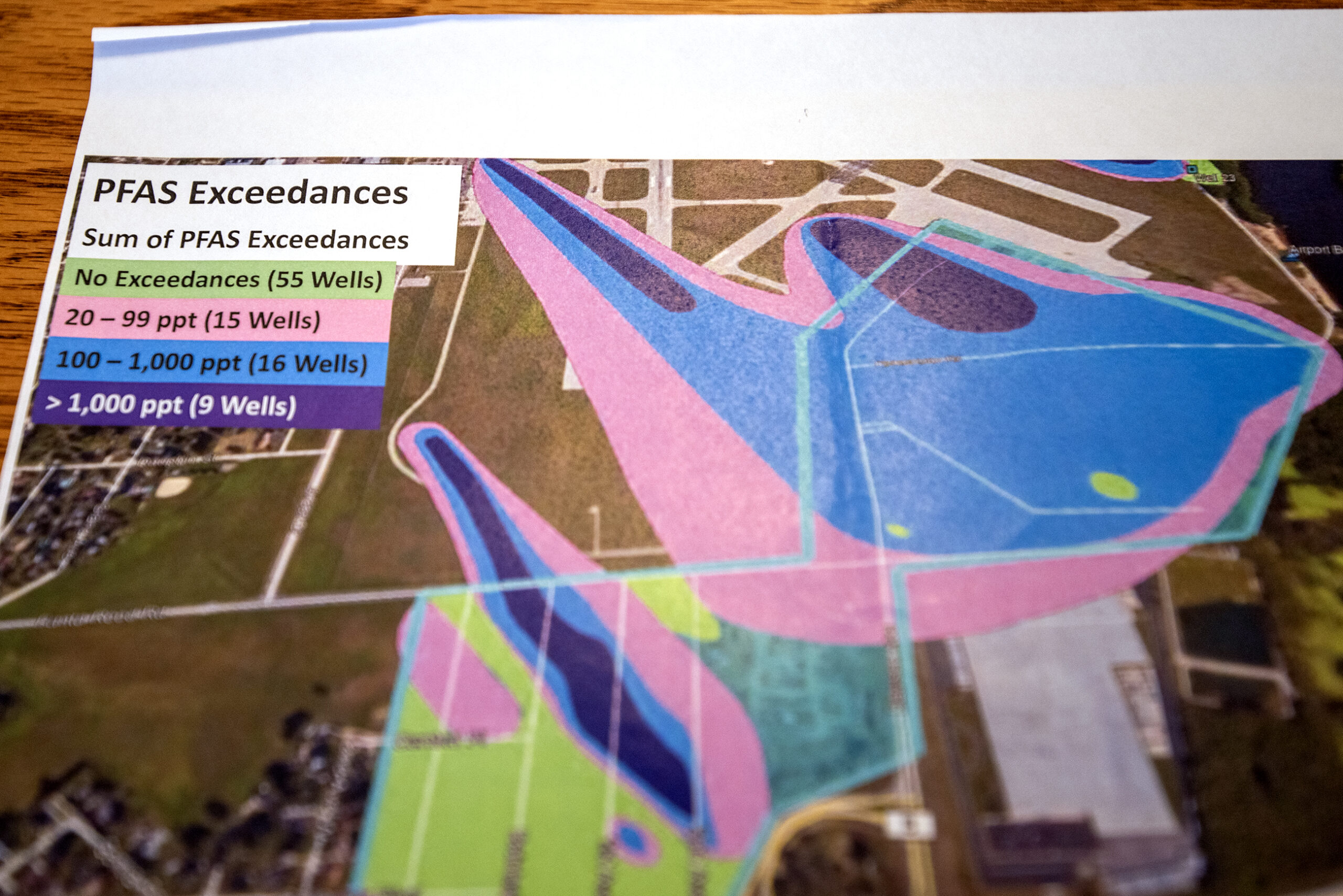

The state Department of Natural Resources ordered an investigation into PFAS levels on French Island in 2019. Testing showed that hundreds of private wells on the island had PFAS levels deemed unsafe for drinking by the state Department of Health Services. The DNR ordered the city of La Crosse to provide affected residents with bottled water, and the DHS later declared an area-wide drinking advisory that is still in effect.

Boisen and Walker received their first water delivery from Culligan on Christmas Eve in 2020. Ever since, they have been avoiding tap water for drinking, cooking and toothbrushing, and instead they use water from 5-gallon jugs and individual bottles.

Boisen, 83, has to roll the heavy jugs across the floor to get them to the kitchen water dispenser. He said everything takes longer, whether it’s filling a mug for morning coffee or stowing jugs in the basement after they are empty. The couple no longer has room to store their shoes in the front closet — the space is filled with water jugs.

As the community awaits a permanent solution to the PFAS problem, Boisen worries that he and Walker, now 78, might not have time to return to their former lifestyle and hobbies like cooking, gardening and fishing.

“It’s a little bit depressing when your dreams of, ‘This was going to be our place where we were going to live as long as we could,’ and this water thing just kind of put a kink in it,” Boisen said. “We’re going to stay here as long as we can anyway, even if we’ve got to drink bottled water all the time.”

Wisconsin invests in testing and removing harmful PFAS chemicals

The use of these toxic “forever chemicals” dates back decades, starting with nonstick cookware in the 1940s. Since then, PFAS have been used in everything from food packaging to clothes and consumer products like cosmetics and dental floss, according to the National Resources Defense Council.

They get that name because of the strength of the chemistry at play with these chemicals, said Gavin Dehnert from Wisconsin Sea Grant and University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“They have a carbon-fluorine bond — one of the strongest organic bonds that is known to exist,” Dehnert told “Wisconsin Today.”

But attention on the harms from these chemicals is relatively new.

“I like to always say that we know less than what we don’t know,” Dehnert said. “That’s partially due to the fact that the PFAS have really hit the scientific radar in the last seven [or so] years.”

Dehnert said that, while the price of a test for PFAS has decreased in recent years, it can cost upwards of $350 to $400 to test a single well or water source.

There are 800,000 private wells in Wisconsin and 11,000 public water systems, with more than 575 of those being municipal and investor-owned drinking water utilities.

Gov. Tony Evers’ latest budget proposal calls for more than $145 million to address PFAS contamination around the state, with most of the money going to PFAS testing in municipal drinking water systems.

Town of Campbell makes headway on addressing PFAS contamination

Since discovering that French Island’s water supply is contaminated with PFAS, officials and advocates have tried for years to find a way to treat their water or find new water to drink. Local officials made a breakthrough last year when a team drilled test wells in the deep Mount Simon-Hinckley aquifer to find new sources of clean drinking water.

Lee Donahue is the town of Campbell’s health, education and welfare supervisor. She said the years of research on French Island’s contaminated water could yield valuable information for other communities dealing with PFAS pollution, even if a deep well isn’t a solution that will work in every community.

Donahue said the town is aiming to have their own municipal water system — drawing from the Simon aquifer — up and running by the end of 2027.

“I know that seems like a long time away. But compared to where we were in October of 2020 … people are going to see this within their lifetime,” Donahue said. “That was a question that many people asked all along: ‘How long is this going to take? Will I ever see it come to fruition?’”

‘French Island water was lovely,’ Boisen says

Evers and Karen Hyun, head of the Wisconsin DNR, recently visited French Island to get updates on the new well and hear from residents like Boisen and Walker about how PFAS contamination has affected their lives.

On the day of the governor’s visit, Walker wore a sweater with the words “French Island” embroidered on it. She said people on the island used to take great pride in the taste and quality of their local drinking water.

“Everybody that was there [at the meeting with the governor] talked about how great our water was,” Walker said. “We loved the water on French Island, not knowing that it was contaminated.”

Boisen and Walker hope they will be around for the day they can safely drink their tap water again. They take heart in the fact that the new well is on the way.

“It gives us peace of mind of a sort. The problem isn’t solved, but at least they have a time frame,” Boisen said. “I just hope we’re around long enough to enjoy some more nice French Island water.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated Monday, March 24 to remove a data point about private well contamination on French Island that has since been updated with additional testing.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.