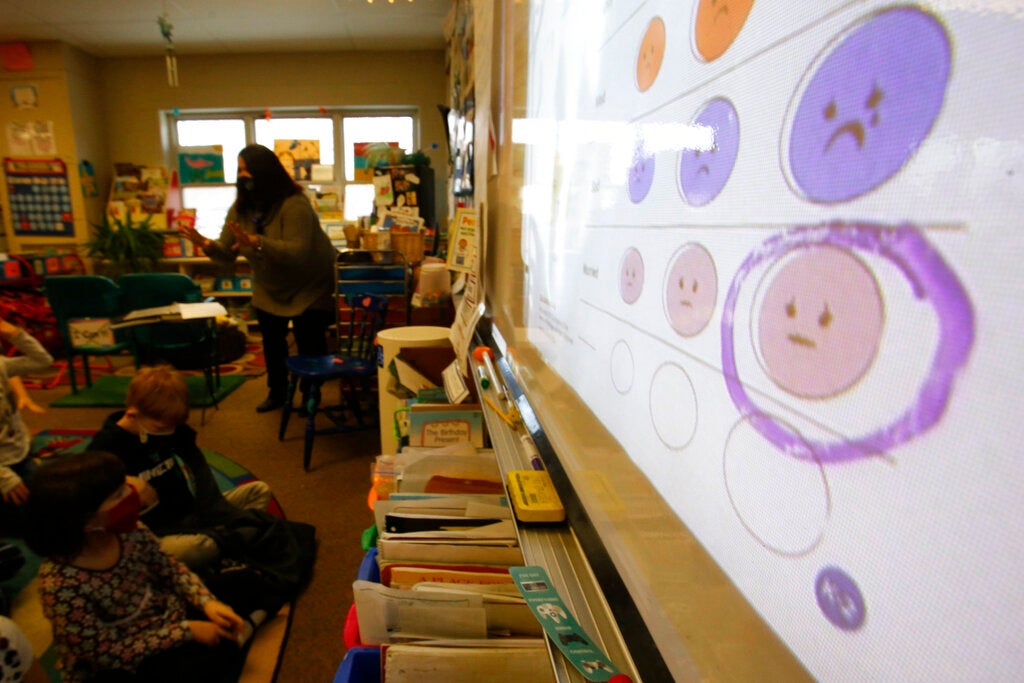

New funding to a Milwaukee program would provide more frontline workers to help children and their families heal after interpersonal violence.

Project Ujima, through Children’s Wisconsin, provides free services — including safety planning, school and court advocacy and long-term mental health care coordination — to reduce the number of children harmed by violence.

Milwaukee’s fatal and nonfatal shooting rates have fallen over the past two years, following national trends. But Project Ujima has seen more cases this year than in the two years prior. The project has been forced in the past to turn away patients or families, according to reporting from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Last month, the national nonprofit Everytown Community Safety Fund committed $2 million to community-based violence intervention organizations around the country. Project Ujima received $100,000 of that funding.

Project Medical Director Dr. Michael Levas, on WPR’s “Wisconsin Today,” said Project Ujima attempts to interrupt a cycle of violence. For years, car accidents have been the leading cause of death among children and adolescents. But data from the Centers for Disease Control shows that guns became the leading cause in 2020.

“The No. 1 reason I have to tell a family that their child is dead is because of firearm violence or firearms,” Dr. Levas said. “It’s not cancer, it’s not asthma — it’s firearms. So anything that our crime victim advocates can do to stop that cycle is saving lives down the road.”

The following interview was edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: The recent $100,000 grant from the Everytown Community Safety Fund is aimed at hiring more crime victim advocates to work with youths and families enrolled in Project Ujima. What do these advocates do?

Dr. Levas: The crime victim advocate is really trying to get to youth and impart on them that they don’t have to continue the cycle of violence. We know that being shot once is the most likely predictor of you being shot again.

We also know that being a victim of interpersonal violence increases your likelihood of becoming a victim again or becoming a perpetrator of violence. And we also know that being shot once decreases your life at your five-year life expectancy.

(The advocates also) become a mentor. Mentorship is one of the strongest evidence-based interventions for a variety of social stressors. Advocates serve as a mentor, as a trusted adult, a positive role model, and then help those youth identify who else in their lives are those positive adult role models.

Kate Archer Kent: Gun violence in Milwaukee has been trending down in recent years. There have been 118 homicides in Milwaukee this year, 31 fewer than at the same time last year. But referrals to Project Ujima this year have outpaced referrals from the two years prior. Why?

Dr. Michael Levas: It’s true, the amount of homicides and fatal gun violence across the country has trended down. I think a lot of that is due to a lot of programs like Project Ujima.

What we have seen is that the ages of violently injured youth have shifted downwards. So even though there are fewer homicides and less volume on the adult side, a lot of pediatric hospitals across the country are seeing an increase in referrals. Because it’s our youth that are really not seeing that change in incidents of violent injury.

We don’t just see youth who are shot. We see kids who are victims of physical assault as well, because we know that if we look back at youth who are victims of gun violence, there usually has been a pattern of more risk-taking behavior that leads to that firearm injury. So we try to intervene early. We will take referrals for someone who was jumped or someone who got into a fist fight at school.

There’s also vicarious trauma. We don’t just take the incident victim. We will see their siblings, because we know that having someone you love either murdered or physically assaulted, that can be scary for your siblings as well.

KAK: Why are the ages of violently injured youth trending downwards?

Dr. Levas: I think what we’ve seen is disinvestment in youth.

Really, a lot of stuff happened. A lot of the increase with youth being violently injured or being victims of violence coincides with COVID-19. Most of your urban school districts went virtual. They canceled a lot of their after school programming. They didn’t do sports and they took longer to come back to being non-virtual, took longer to reinstate athletics. They took longer to reinstate their extracurriculars.

I think anytime you do not allow for youth to have pro-social engagement, you run the risk of them engaging in risk-taking behaviors. And then if you have years of that, I think that you have a series of disinvestments where the kids are feeling like they have less and less of those options. They have less opportunity, and they make poor choices. And then the cycle continues.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.