When Josie Lee from the Ho-Chunk Nation looks at Wisconsin today, she sees the impact of her tribe on the state.

“If it weren’t for Ho-Chunk people, we wouldn’t have the state as it exists today,” Lee told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “You wouldn’t have such a large agricultural industry with cranberries if it weren’t for seasonal Ho-Chunk migrant workers in those fields. Nor would you have the tourist industry of Wisconsin Dells as it stands today, without H.H. Bennett taking pictures of Ho-Chunk people and saying, ‘Come look at the Indians.’”

Lee is the director of the Ho-Chunk Nation Museum Cultural Center in Tomah, which is marking five years since it opened in 2020. The building suffered fire damage last year and hasn’t yet reopened to the public, but Lee continues to oversee cultural programming.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The museum’s collection, which was not damaged in the fire, includes items like Ho-Chunk baskets, hand-stitched appliqué and watercolor paintings by Clarence Monegar. For Lee, it’s important that tribal members can see themselves in the collection and learn how to carry forward artistic and cultural traditions that interest them.

“We try to focus a lot of the attention from the past in the reflections of how it looks here in the present day, and what we can take from those things that were brought to us by our ancestors and really continue on in future generations of learners,” she said.

On Wednesdays, Lee runs a “brown-bag craft lunch” at the tribal executive office in Tomah, where people can work on projects together. She also teaches arts and crafts classes online so tribal members from anywhere in the country can join. Lee has taught how to make traditional dresses and Pendleton coats, and she has a moccasin-making event coming up in March.

“Really, if there is something that tribal members want to learn, I will figure [it] out,” she said.

In all of her work, Lee emphasizes that Ho-Chunk culture isn’t just a thing of the past.

“It’s important to remind your average everyday citizen that Ho-Chunks have continued to exist alongside everyone else,” she said. “We are still here, still using our language and speaking that today, as well as using our culture and making sure that it is present and highly visible.”

Wisconsin historian rethinks Ho-Chunk removal history

However, it’s not inevitable that Ho-Chunk people would still be in Wisconsin today given the centuries of attempts by European settlers to eradicate them and their culture.

From the 1820s to the 1870s, Ho-Chunk people faced what historian Stephen Kantrowitz calls a “long removal era,” when the federal government tried to forcibly evict them from their ancestral lands in Wisconsin.

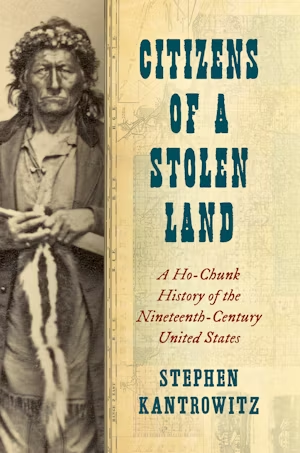

Kantrowitz, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, wrote “Citizens of a Stolen Land,” chronicling this history and the creative ways that Ho-Chunk resisted removal through claiming land ownership and U.S. citizenship.

“Those 50 years are years of tumult and trauma and enormous loss, in which the federal government repeatedly tries to deport or exile — banish — the Ho-Chunk from their homeland to territories west of the Mississippi River,” Kantrowitz told “Wisconsin Today.”

“It’s also a story of Ho-Chunk people refusing to be banished from Wisconsin, of quickly returning once banished from Wisconsin, and of … coming up with creative strategies that will enable them to create a stable existence for themselves, even as the landscape that they’ve called home is filling up with settlers,” he added.

Kantrowitz said that he was inspired to radically rethink this history after teaching a Ho-Chunk history class at UW-Madison in 2018 that was open to tribal members. One day, he shared a map of the expulsions and returns of Ho-Chunk people from Wisconsin in the 19th century. In previous classes, this map had generated lively class discussion among students. This time the class fell silent.

Finally, one tribal member spoke up.

“I’d rather talk about a different map,” she said. “I want to talk about the map of the places they told us never to go. I want to talk about the stories they told us about why.”

This moment has stayed with Kantrowitz.

“I’ve never really been able to shake that — that what I had thought of as a kind of history that was bounded in time was a history that was continuing, that was very much live in the experiences and the daily lives and the family stories of Ho-Chunk people today in the 21st century in Wisconsin,” Kantrowitz said. “That lesson has really changed how I have thought about the entirety of Ho-Chunk history.”

Kantrowitz hopes that the book is a starting point to help Wisconsinites understand this difficult but important chapter in state history — and that history is never really behind us.

“I’m hoping that it adds some some depth and some nuance to histories that are frequently told as histories of ‘Badgers,’ of Gov. [Henry] Dodge as a kind of heroic figure, an American pioneer, and instead recognize we’re talking about a history that begins in a squatter conquest of another people’s homeland,” he said. “To the degree that we soft-pedal or ignore or just are ignorant of that, I think we misunderstand the struggles that we have had and continue to have in building an actually multiracial, multicultural society, which is what a nonracial democracy is supposed to be.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.