Town of Peshtigo resident Cindy Boyle was delighted when she received notice from her insurance company about a change in her policy that would alarm many business owners.

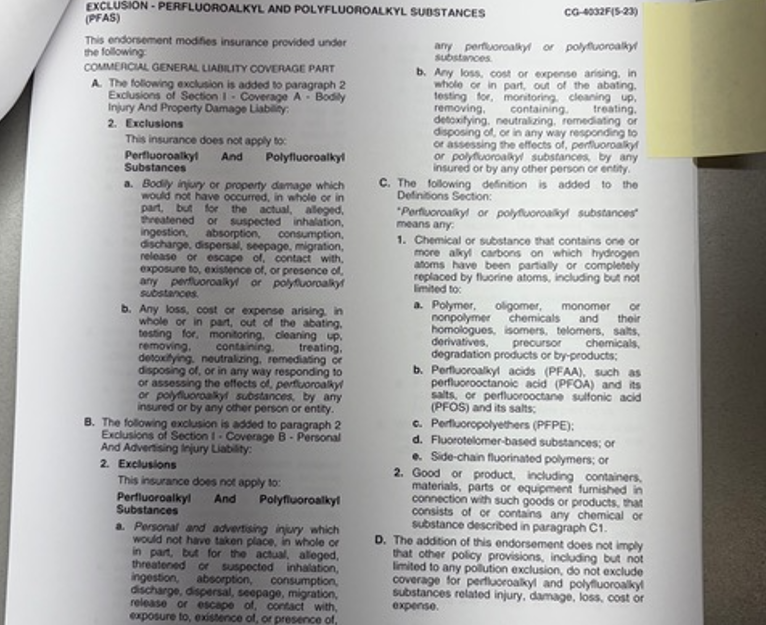

Boyle, who co-owns a graphic design and sign company, was reviewing the renewal of her commercial liability policy with Sheboygan-based Acuity Insurance. She noted it listed exclusions for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS.

Under the changes, coverage for bodily injury or property damage stemming from the chemicals would now be expressly denied.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Boyle said she was excited to see the change as she and town residents have been struggling with PFAS contamination stemming from Tyco Fire Products’ fire training facility in Marinette.

“If businesses can’t get insurance to cover them from the liability of using PFAS, then they’re going to be far more motivated to stop using PFAS in their manufacturing,” Boyle said. “The less it’s used in manufacturing, the less it gets into the groundwater, in the air. Then, the more people like me and others can have confidence that this ongoing use and exposure is starting to be reduced.”

A spokesperson for Acuity did not respond to requests for comment.

Rural Mutual Insurance Company also notified Wisconsin farms that they would not pay losses stemming from PFAS pertaining to bodily injury, property or environmental damage or cleanup costs. The company provides coverage to members of the Wisconsin Farm Bureau Federation.

In an email, a company spokesperson said the Insurance Services Office, which advises the property and casualty insurance industry, rolled out endorsements for PFAS exclusions. In June, Rural Mutual and many other insurers nationwide adopted the forms excluding coverage for PFAS.

“Rural Mutual has never covered PFAS at any time in the past and these exclusions were added to clarify language so customers understand exactly what is and is not covered (emphasis included),” the spokesperson said. “PFAS exclusions limit risk and mitigate potential costs that could significantly impact Rural Mutual’s ability to do business.”

The company said it’s dedicated to serving the Wisconsin community, and it considers the best interests of both policyholders and continuing the business when excluding certain risks.

Pollution exclusions are common

Pollution exclusions are commonly found in liability insurance policies, according to Alex Lemann, associate law professor at Marquette University Law School. They began in the late 1970s and early 1980s when Congress passed federal laws governing hazardous waste or substances.

Those laws include the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act or Superfund law. The former controls hazardous waste while the latter allows federal regulators to force polluters to pay to clean up hazardous substances.

“In the decades since then, the insurance companies have expanded the way they’ve written these exclusions so that they’re now very broadly worded,” Lemann said.

Steph Tai, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Law School, said many insurers wanted to avoid paying for cleanup costs. Despite broad language, some insurance companies were ordered to pay hundreds of millions of dollars. Tai said that’s prompted more express exclusions, such as those for PFAS.

“I think it’s partly because a lot of insurance companies have realized how much they’ve been spending on defending companies in this litigation,” Tai said. “They just want out.”

Companies face billions in lawsuits over PFAS contamination

Companies like Minnesota-based 3M are facing billions of dollars in lawsuits over PFAS contamination stemming from their products. Earlier this year, a federal court in South Carolina approved the company’s settlement with water systems where 3M will pay between $10.3 billion to $12.5 billion through 2036. The New York Times also reported earlier this year that a defense lawyer warned the plastic industry to prepare for “astronomical” costs from PFAS litigation.

For policyholders with PFAS exclusions, Tai said they’re on the hook for any damages. That could affect not only companies that have released the chemicals into the environment, but those that use PFAS in food packaging and other products. If people have questions about PFAS exclusions, Leman said it can’t hurt to ask their insurance agent about how it may apply to their business.

Boyle noted the changes come as the Environmental Protection Agency has designated two of the most widely studied PFAS chemicals as hazardous substances.

“Those who’ve been cutting the check around this problem think it’s also harmful, at least financially, to them,” Boyle said. “They’ve decided not to bear that expense anymore.”

State Sen. Eric Wimberger, R-Green Bay, said he was unaware of the changes, but he anticipated insurers may seek to reduce their risks.

“Something that was not considered officially hazardous is now becoming officially hazardous,” Wimberger said. “The effect of this is that people are being found to own brownfields, and so insurance companies are going to take that into consideration and develop their policies accordingly.”

Wimberger said the changes underscore the need to protect innocent landowners from liability.

The Green Bay lawmaker introduced a bill that included such protections as part of a plan to spend $125 million to address PFAS contamination. That provision drew concerns from Gov. Tony Evers and environmental groups. In April, Evers vetoed the bill over fears it would limit the authority of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources to require polluters to test and clean up contamination under the state’s spills law.

In Wisconsin, Republican lawmakers have said they want to give farmers and landowners peace of mind that they won’t be held financially liable if they apply for grants to clean up PFAS contamination. Farms have often spread biosolids, or treated sewage sludge, on fields that may contain PFAS.

The DNR’s interim strategy for biosolids states around 85 percent of all biosolids generated are reused on land for nutrients. The DNR has previously estimated that biosolids have been spread on at least 70,000 acres in the state. A DNR spokesperson didn’t provided updated figures on the amount of land or farms that have received biosolids.

The DNR has said the agency has not and does not intend to pursue farmers for costs tied to unintentional PFAS contamination from land spreading in line with enforcement policy guidance issued by the EPA earlier this year.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.