Editor’s note: This story contains language and descriptions surrounding abuse and assault.

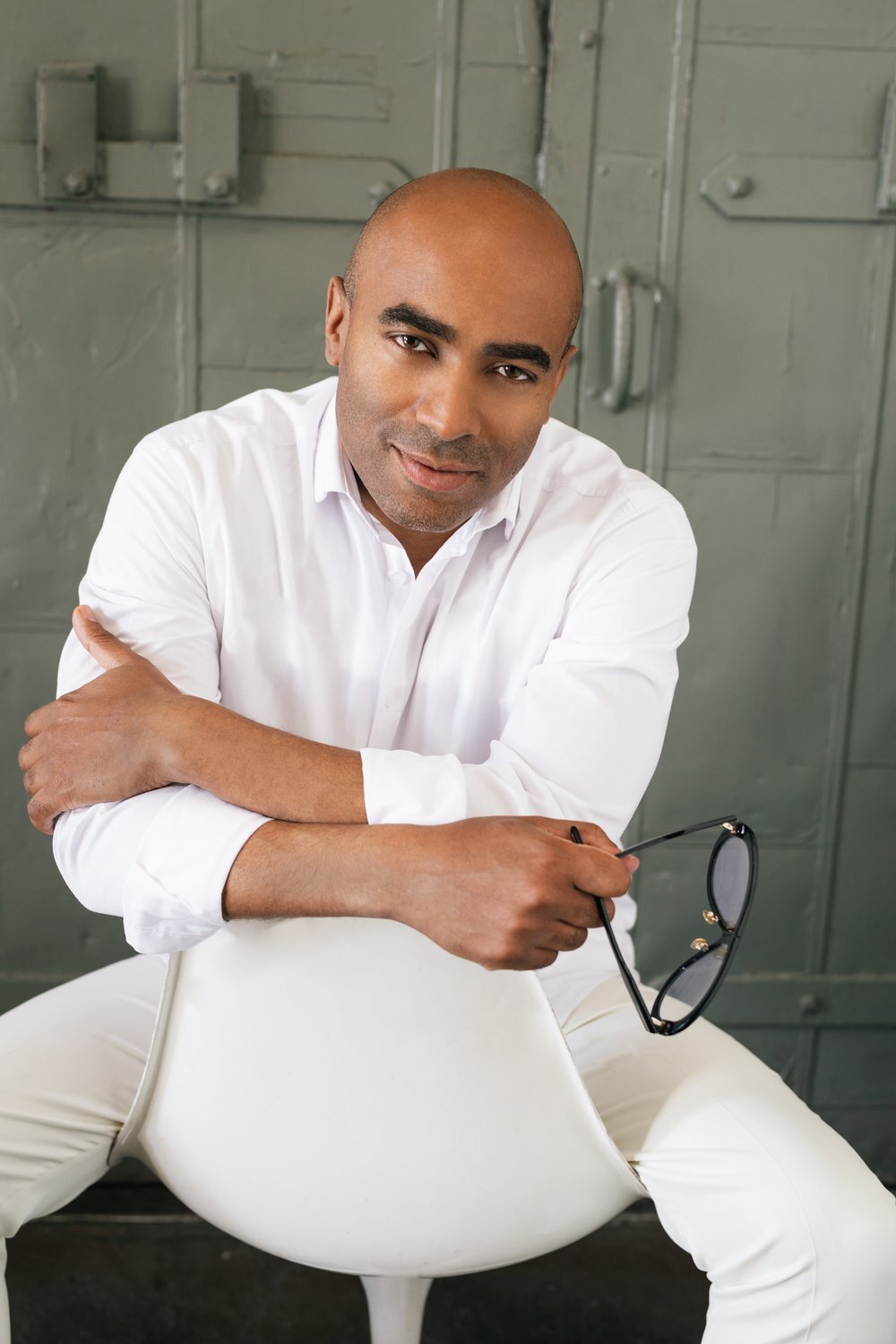

When Lee Hawkins was a budding journalist writing for The Badger Herald at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the early 1990s, he was just beginning his decades-long journey to understanding the connection between his family history and the physical abuse of his childhood.

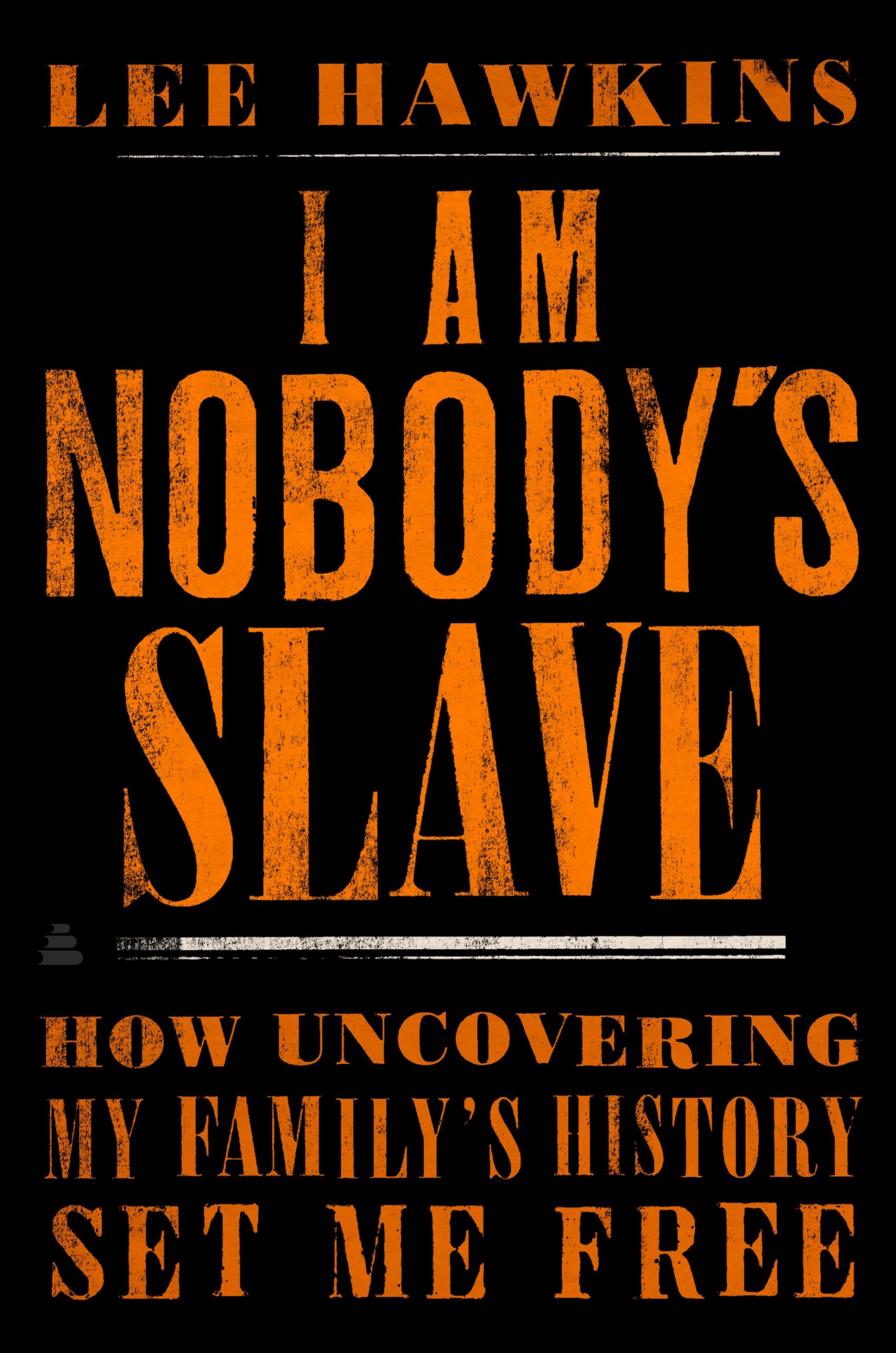

It was at that time that Hawkins and his father went to Alabama to visit his father’s uncle, Ike Pugh, to learn more about their family history. The information he learned on that trip — about the violence his family endured, the existence of his white relatives, and the great-great grandmother who lived through enslavement — inspired his new memoir, “I Am Nobody’s Slave: How Uncovering My Family’s History Set Me Free.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“(Uncle Ike) was giving us this piece of American history that was so critical to this project,” Hawkins told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “I got away from it for many decades, but the seed for this project was planted on that trip.”

After attending UW-Madison, Hawkins went on to write for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and the Wisconsin State Journal. He later became a writer for The Wall Street Journal. During that time, Hawkins writes, “My interview with Uncle Ike would slip from memory as my budding career in journalism blossomed.”

But eventually, he said nightmares of the abuse he endured from his parents in his childhood demanded he return to his family history. He began going to therapy with his parents, which is where he first found the words that would become the title of his memoir.

“In my discussion with my parents, I said, ‘I’m nobody’s slave.’ That was probably my first understanding that so many of the things that I was struggling with were vestiges of slavery,” Hawkins told “Wisconsin Today.” “But I could not put my finger on the truth, because I hadn’t done the research.”

Author searches for ‘the truth of America’

In order to further understand his own struggles with mental health, he traced his family history and the history of violence toward Black people in the United States.

Part of his research led him right back here to Wisconsin. He took a DNA test that revealed more European ancestry than he thought — almost 20 percent of his DNA traced back to Wales. He found out that he had living white relatives. In fact, he had known one of them for 30 years. That person was a public relations professional for the Wisconsin Chamber of Commerce whom he talked to regularly in his early journalism career.

Through genealogical research, Hawkins said, “I found out so much more about the truth of America and why it is that so many African Americans have European DNA.”

The truth, he said, was that his ancestral connection with his white relatives was likely the result of sexual assault on enslaved women by their white captors.

He also found that history impacted his family beyond their DNA.

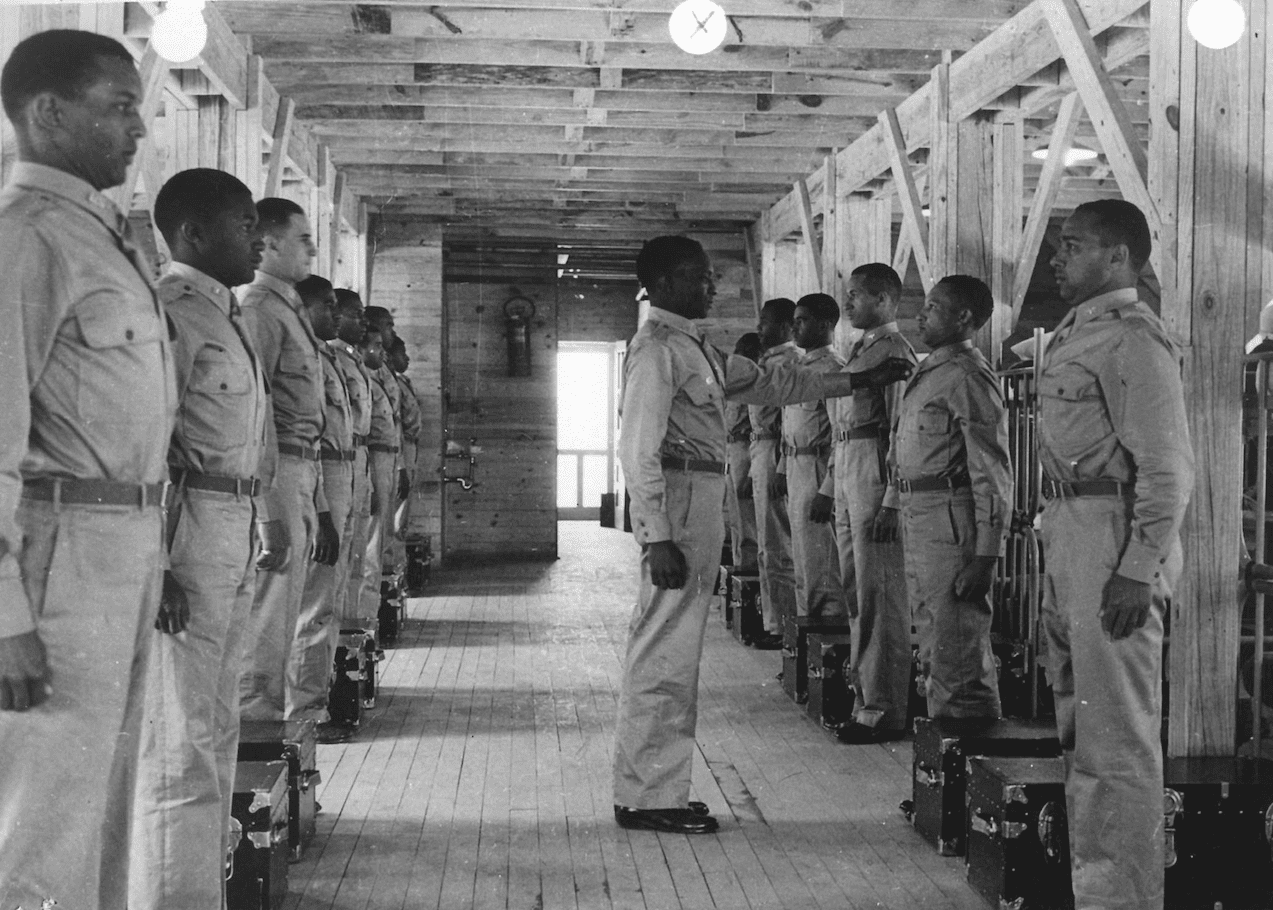

“This book is a 400-year investigation into the intergenerational effects of slavery, Jim Crow and the Great Migration, on the way that I and many other Black people whose ancestors lived through (those events) were raised,” Hawkins said.

Hawkins came to the conclusion that the abuse he endured as a child was an extension of the whippings that enslaved people endured generations ago. In his memoir, he argues that Black parents like his own unintentionally became the enforcers of white oppression out of their concern for their children’s safety.

“In the community that I was in, the belt was seen as a protective measure to keep a Black child from getting killed by the police or getting killed in their community,” Hawkins said. “It was used to scare us into perfect behavior.”

The complexity of his relationship with his late father is yet another parallel Hawkins draws between his own life and the history of Black Americans.

“It’s really hard for people … to get their minds around how someone who could spank you with a belt could also be as present and loving as my father was,” Hawkins said. “And that complexity is something that I feel about my country, too. How could a country that is supposed to love us be so cruel to us as African Americans?”

Exploring that complexity with his family required Hawkins to approach their conversations with love and openness — something he suggests other families do when talking through their shared trauma.

“I believe that the highest form of love is actually curiosity and asking questions. Why did this happen? How did this happen? What was happening at the time when this happened?” Hawkins said. “We became closer through this process, because this forced us to learn to confront the past and move forward together.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.