High-stakes bets on timber-hauling livestock contests. Deadly rafting to float logs down Wisconsin’s rivers. These are just some of the stories that the state’s thousands of lumberjacks would sing about to pass the time at logging camps after a long, dangerous day’s work.

And thanks to these songs — and their preservation by folklorists — we have additional insight into the lives of these iconic workers, says Matt Christoff, a baritone singer from Dyckesville who is seeking to revive this history for a new generation.

Christoff recently returned to St. Norbert College, his alma mater, as a guest artist. As part of his visit, he gave a lecture about lumberjack songs of the Upper Midwest from the 19th century.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

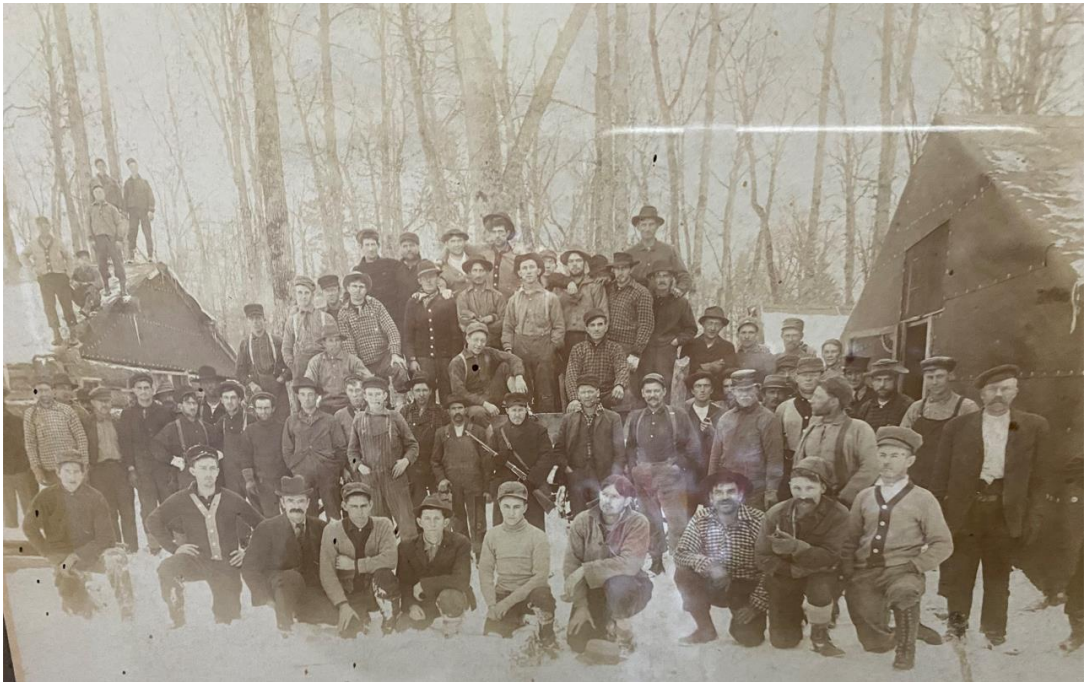

He told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” that he became interested in exploring this history because of his own roots in the area. Growing up in the Northwoods, Christoff has family connections to the logging culture of the region. His great-great-great grandfather, Joseph DeBaker, was the foreman for a lumber camp near Randville, Michigan.

With the help of his uncle, a silviculturist for the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest, Christoff gained access to the U.S. Forest Service archives about the music at the lumberjack camps. From there, he said he was hooked.

Christoff was also inspired in his research by “Pinery Boys,” a book from UW Press about the work of Franz Rickaby, a folklorist and “song catcher” who documented the lumberjack songs of northern Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota after traveling through the area in 1919.

Music to survive by

“They brought the music that they knew, and they adapted it to talk about life in camp,” Christoff said. “They mainly sang ballads that talked about the history of what was going on in camp, personal stories, tall tales, and, of course, chronicling some tragedies and comforting (themselves) while they were isolated out in the woods with no one around.”

Christoff said one of his most surprising discoveries while undertaking this research was that lumberjack songs were considered occupational songs — not work songs — meaning they weren’t sung on the job.

“If you think about it, you’re using an axe, you’re using a saw, you’re spread really far apart and doing very dangerous work that requires a high amount of focus,” he said. “So they weren’t able to chop down a tree and sing. They’d be doing that at the bunkhouse after the job was done.”

As part of his presentation at St. Norbert College, Christoff created a playlist on Spotify titled “Shanty Boys” that contains nearly five hours of lumberjack songs.

“At first, it was purely Wisconsin tunes, and then it became Upper Midwest tunes,” he said. “And then (through) my research, I came to find that they also sang other professions’ songs for entertainment, so in came sea shanties and other kinds of work and occupational songs, and it took off.”

Christoff shared the history behind several songs that appear on the playlist.

‘The Little Brown Bulls’

This song is said to have its origins in Wisconsin — somewhere between Plover, Chippewa Falls and Crandon, Christoff said. It tells the story of two teams of livestock pulling pine at a lumber camp: the “big spotted steers,” who are favored to win, and the “little brown bulls” of the title, who are the underdogs.

McCluskey, called “the Scotsman” in the song, owns the steers. He is so confident he will win the contest over rival Bull Gordon and his “little brown bulls” that he bets his mackinaw jacket (a classic wool coat of red plaid) on top of the $25 bet they’ve made.

“At the end of it, the scaler — the person who climbs the huge stacks of wood to measure them — says, ‘Well, you did meet your contract, McCluskey, but Bull Gordon, he beat you by 10-and-a-score,” Christoff said. “So [McCluskey] gave his mackinaw and his $25 to Bull Gordon, and they drink to the hardest day’s work that was done on the Wolf River.”

‘The Pinery Boy’

This is “a true Wisconsin classic of a lumberjack song,” Christoff said. The lyrics tell the story of a woman who rides a boat down the Wisconsin River in search of her lover who works as a raftsman, whom she calls her “pinery boy.”

Christoff explained that the job of a raftsman — floating the logs down the river and breaking up log jams — was very dangerous.

“For every raftsman who left their partner to go out on the big rivers like the Wisconsin, the St. Croix, the Mississippi, the Wolf, there was the reality that they may not come back,” he said.

This is the sad fate of the “pinery boy” in the song as well. When the woman receives the news that her lover did not make it, she rows to the Dells to seek out where he was laid to rest at Lone Rock.

“It’s just a very memorably tragic and beautiful song,” Christoff said.

‘The Lumberjack Alphabet’

Christoff performed this song in the WPR studio. It’s a lively tune that outlines the ABCs of lumberjack life, from “A” for “axe” to “W” for “woods” (a comic bit in the song is that the singer skips X, Y, and Z).

Christoff explained this is meant to be an “instrumental song to teach a variety of people from all sorts of backgrounds skills that they needed to survive very quickly.”

“The foreman might assess a person who wanders into camp within a couple minutes and go, ‘That’s your job. Go do it,’ and you need to kind of just pick up the skills as you go,” he said. “Using the alphabet as a mnemonic device to remember all these skills is very creative.”

Lessons from the past

For Christoff, a big takeaway of his research into lumberjack songs is that you don’t need a formal education to participate in a lasting musical tradition.

“These men were mainly there to chop wood, but they still found time to carve out tunes and lyrics, and we’re still talking about them today and they’re very much a part of our identity as Wisconsinites still,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.