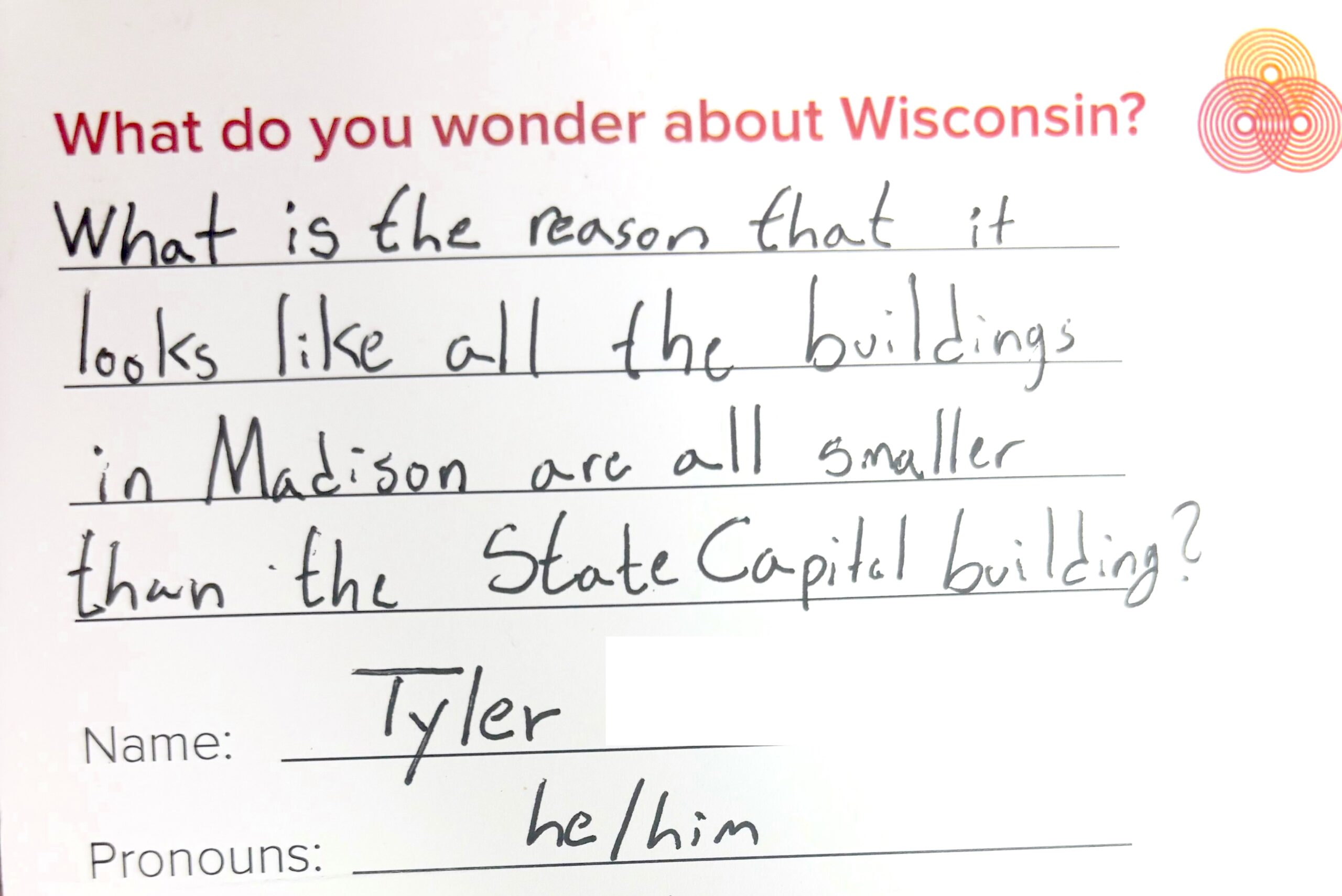

A listener in Milwaukee recently sent in this postcard:

To get to the bottom of Tyler’s question, WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” talked to the city of Madison’s planning division director, Meagan Tuttle.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“This is certainly something that anyone moving around Madison these days can see pretty clearly,” Tuttle said. “There is, in fact, a law in the city of Madison related to where and how buildings downtown can be developed to help protect important views of the Capitol.”

According to Tuttle, the “Capitol View Preservation Limit” is part of a series of zoning laws in the city of Madison that limits the height of buildings within 1 mile of the center of the Capitol to not exceed the height of the base of the capitol’s columns, “essentially making sure the dome remains the prominent feature within our downtown landscape.”

“Ultimately, it’s about the recognition that the Capitol sits on the highest point on the isthmus downtown,” Tuttle said.

There is a state statute that’s even more specific: No building can be taller than 1,032.8 feet above sea level if it is within 1 mile of the center of the Capitol.

Tuttle said that zoning laws in other areas of the city prioritize growth and are generally more permissive than those downtown.

Zoning laws in Madison must also account for city infrastructure and investments, such as the transportation system.

“Limits like (the Capitol View Preservation Limit) can sometimes push and pull the development priorities and opportunities,” Tuttle said. “When we’re talking about planning, it’s about how future development happens. It’s about how the size and scale of new buildings fit in with the existing context.”

Anna Andrzejewski, a professor of American art and architecture at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told “Wisconsin Today” that zoning laws are part of democracy in the United States, because they give people the opportunity to have a say in what their cities look like over time.

“In Madison in 1966, as the story goes, Van Hise Hall was 14 stories tall and really stood out on campus — and some people in Madison were outraged,” she said. “This is what led to the height restriction that no building within a mile could be taller than the Capitol.”

During the early 20th century when steel frame construction and elevators became more popular, denser cities like New York constructed taller and taller buildings. This darkened the streets significantly because the buildings blocked out the sun — until zoning laws were changed to require the tops of buildings have setbacks that allowed more light into the streets.

“There’s always been that tension between wanting density and density really being efficient and also wanting to preserve things like light and air and having more open space,” Andrzejewski said.

Andrzejweski said that environment shapes our lives and affects how we move through space — and that urban areas are public spaces.

“The street is a public space,” Andrzejweski said. “It affects how people come together, how they live, how they interact, and that’s really true in any environment.”

This story came from an audience question through the WHYsconsin project. Submit your question and we might answer it in a future story.