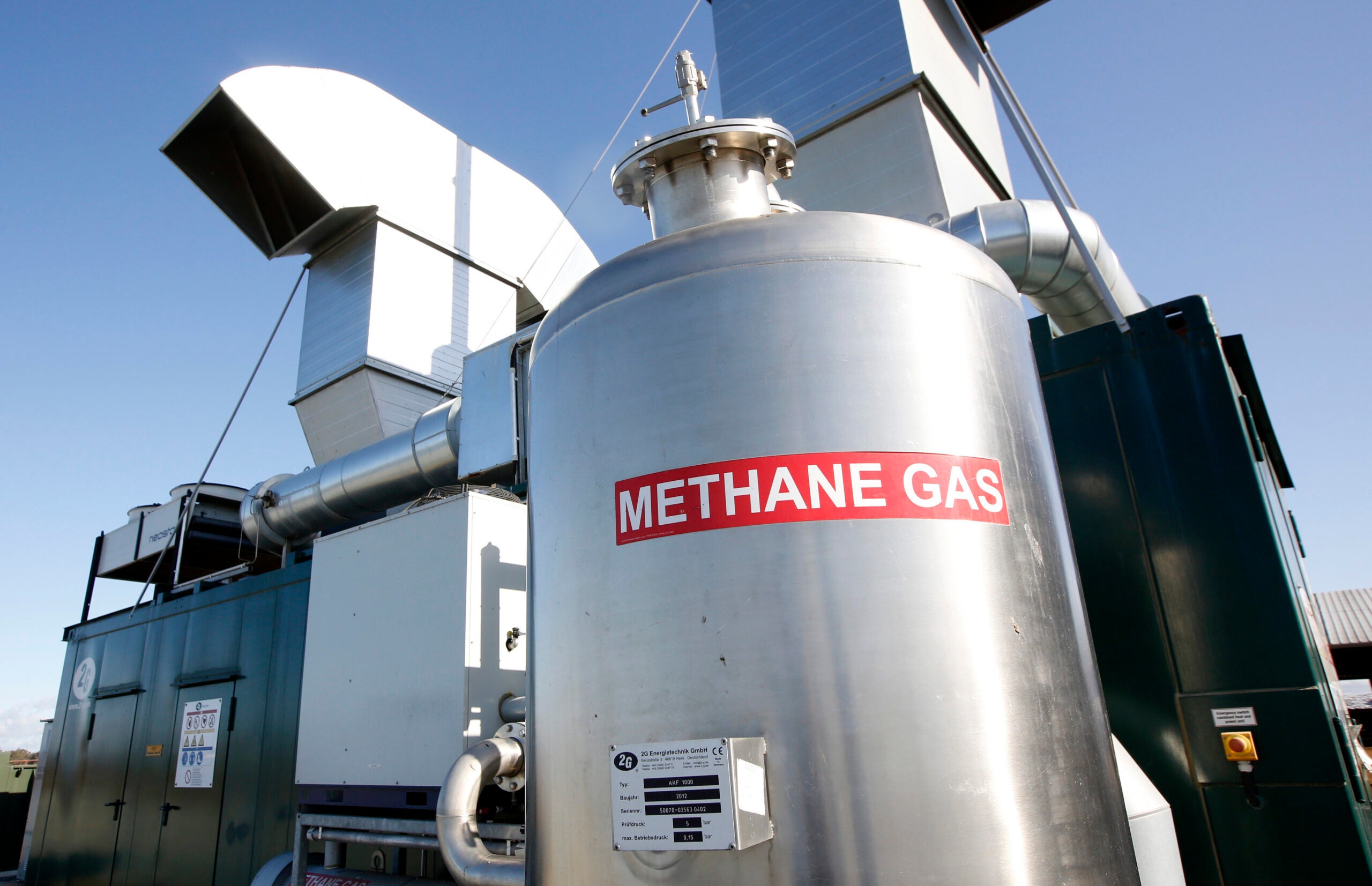

A new report from environmental groups claims manure digesters are encouraging farm expansion and making pollution worse in Kewaunee County. But supporters argue manure digesters help reduce greenhouse gas emissions and provide renewable energy.

Digesters manage organic waste like manure and food scraps using a process where microorganisms break the materials down to produce biogas, which can be used as a renewable natural gas.

The report released by Friends of the Earth and the Socially Responsible Agriculture Project found five of the county’s 18 large livestock farms, known as concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOS, have digesters. It states herd sizes among those farms grew on average by 58 percent since they were installed.

Molly Armus, an author of the report with Friends of the Earth, said that means those operations are generating more air and water pollution in addition to methane emissions from cows.

“This technology is being framed as climate friendly. However, it’s exacerbating the environmental situation that already exists for these communities,” said Armus, the group’s animal agriculture policy program manager.

The report also found the number of dairy cows in the county increased 88 percent in the last 30 years, while the number of dairy farms declined by 82 percent, according to national agriculture statistics.

While the findings don’t prove digesters cause expansion, Armus said the results support the idea that digesters combined with policies that reward biogas production creates incentives for growing dairy herds. She said their use continues practices that have contributed to water contamination in Kewaunee County where cows outnumber people 5 to 1. Research released in 2017 found 60 percent of wells sampled had signs of waste from both cows and people.

Researchers, including Brian Langolf of the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, say digesters cut greenhouse gas emissions by capturing methane from manure in open lagoons. Around 36 percent of methane emissions from human activities are tied to livestock or agricultural practices, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“If instead you’re taking that manure and processing it through an anaerobic digester, you can then harness all of those methane emissions and actually transform it into energy, electricity or transportation fuel,” Langolf said. “You can actually have a negative carbon intensity score, so you sequester more of those emissions than were being released before.”

Wisconsin has more than 300 digesters. Langolf said that includes around 50 dairy digesters on farms. The state is among the top three nationwide with the highest rates of adoption, according to the EPA. The use of digesters on farms has increased due to demand for renewable fuel as the result of incentives or carbon trading, which involves buying and selling credits for heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions like methane.

The EPA states digesters at dairy and swine operations could reduce methane emissions by up to 85 percent or 2.2 million tons each year, but the report’s authors say benefits of digesters are overstated. Another study found digesters could reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions, mostly methane, by 25 percent. But it also found increases in nitrous oxide and ammonia emissions rose by 81 percent.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Deer Run Dairy is one of the five farms cited in the report. Owner Duane Ducat said his dairy of roughly 1,700 cows has one digester that originally produced electricity, but the biogas produced is now converted to renewable natural gas that’s injected into a pipeline.

He said they built the dairy with a digester in mind to take advantage of solid byproducts that can be used for cow bedding, saving costs on alternatives. Ducat added the material left over from the digester, known as digestate, is rich in nutrients that can be more easily taken up by plants. He disputed the group’s findings that use of digesters encourages herd expansion, saying objections to their use has more to do with opposition to large farms.

“I think the main product on a dairy is producing milk, and whatever you can benefit beyond that by having a digester is extra,” Ducat said. “I don’t think you build a dairy so that you can have a digester.”

Part of the reason for that is that digesters are expensive. Langolf said they can cost $20 million to $30 million or more, and they often require larger farms to make them more economically viable.

Case studies of dairy digesters found those that capture gas to produce electricity averaged around 1,950 cows while facilities producing renewable natural gas averaged around 4,000 cows.

Lynn Markham, a land use specialist with UW-Stevens Point, said changes in state policy reduced the profitability of digesters producing electricity, leaving farms to seek other options. She said those include state and federal programs that aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions like the Renewable Fuels Standard and California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standards that provide payments to farms for renewable natural gas.

“And those payments are what are driving the (renewable natural gas) facilities attached to digesters,” Markham said.

Even so, Don Niles, who runs Dairy Dreams LLC in Kewaunee County, said those payments or government incentives aren’t enough to warrant the investment. He also said his digester wasn’t the deciding factor in expansion.

“The biodigesters came in as a better way of running our dairies and protecting the environment,’ Niles said.

The EPA states manure digesters can reduce nutrient runoff into waterways, as well as reduce odors and kill pathogens.

However, the Natural Resources Conservation Service within the U.S. Department of Agriculture notes liquid waste from digesters that’s applied on fields may have a higher risk for ground and surface water quality problems than manure. The reason is that digesters make nitrogen and phosphorus more soluble in water.

Dick Swanson, an Algoma resident, works with the citizen group Kewaunee Cares. He said digesters aren’t the answer.

“I don’t believe this technology to try to clean the water is the answer,” Swanson said. “The answer has always been and will always be to find better fields for your liquid manure.”

The region is susceptible to pollution from manure runoff due to thin soils and fractured bedrock that allow contamination to more easily seep into groundwater. Niles said his dairy, which milks 3,000 cows, uses leftover material from the digester as fertilizer as opposed to adding more nitrogen fertilizer on fields.

“We have to follow the proper application levels with the nutrient management plans,” Niles said. “Those are also based on soil samples of all of our fields to find out which ones are deficient in nitrogen and which are less so because that determines how much manure we apply.”

Environmental groups have said the county’s farms are applying too many nutrients on fields. A 2022 report found nitrogen from manure and fertilizer exceeded rates recommended by University of Wisconsin scientists, noting nitrogen was applied at nearly double recommended levels in Kewaunee County.

Even so, Sara Walling, water and agriculture program director at Clean Wisconsin, said digesters have a place on the farm to reduce environmental risks from the huge volumes of manure generated by CAFOs.

“We are not against digesters, as long as they are being adequately permitted,” Walling said. “I think the (Department of Natural Resources) needs to take a stronger look at the degree of permitting that they’re placing on these facilities.”

She noted the agency has struggled to obtain enough resources and staff to regulate CAFOs. The report stated one farm had 23 spills since installation of its digester, which weren’t directly tied to the system. Farmers say they take precautions to avoid spills and report incidents, adding they want clean water as much as anyone.

While the group doesn’t condone violations from large farms, Walling said it’s important that they’re attempting to deal with the waste they’re generating. Even so, she and Meleesa Johnson with Wisconsin’s Green Fire note the digesters don’t reduce the amount of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus in manure.

“It’s just that you’re just changing them into a different product from raw manure to digestate and liquids,” said Johnson, the group’s executive director.

Johnson agreed with the report’s recommendations that include suggestions for better monitoring and enforcement of nutrient management plans, as well as better regulations and incentives to adopt sustainable farming practices.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.