A recent measles outbreak in Texas, which resulted in one child’s death and at least 20 hospitalizations, has public health officials worried that the highly-contagious disease could come to Wisconsin.

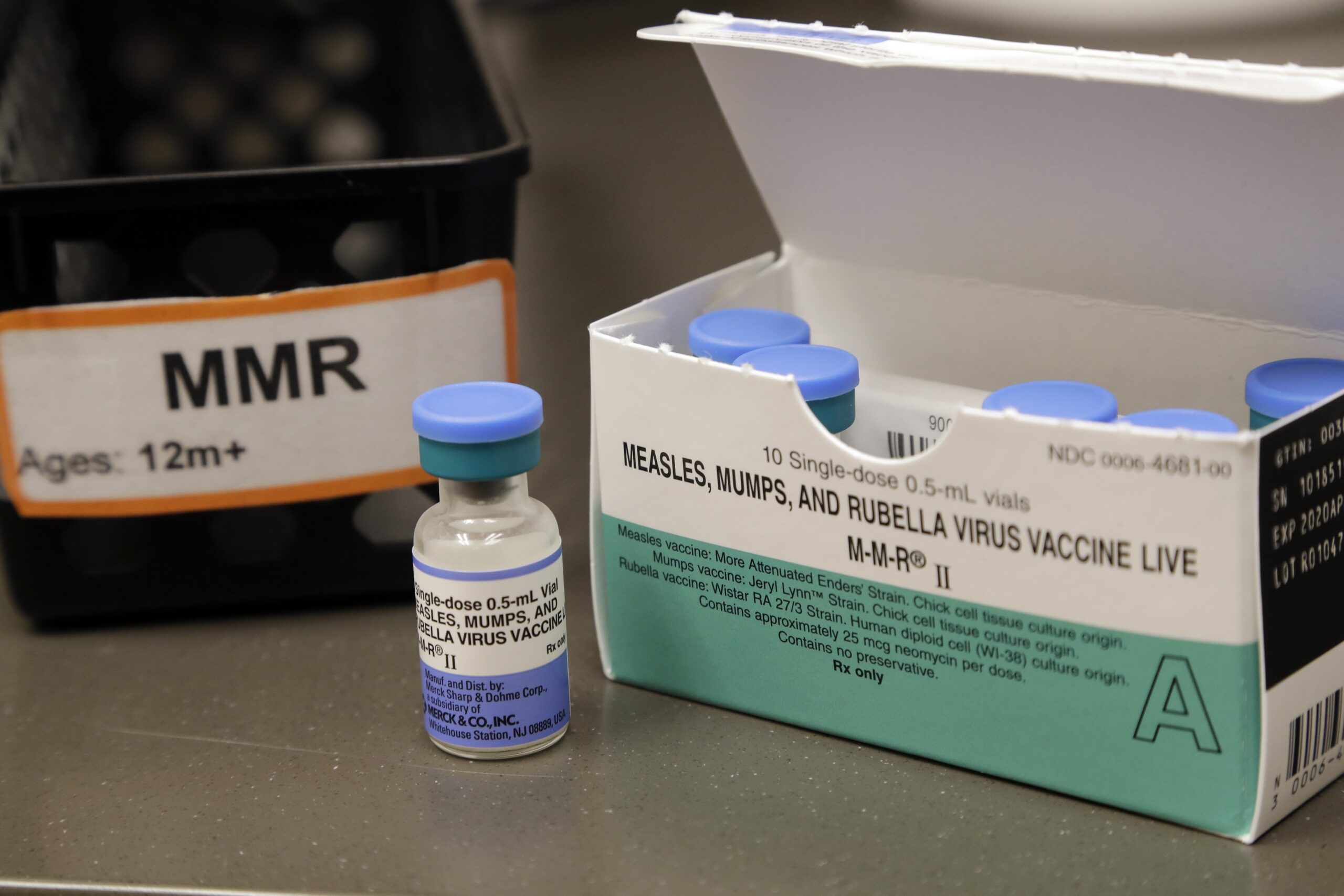

Wisconsin has the second-lowest measles vaccination rate for children nationwide, according to state health data. About 85 percent of Wisconsin kindergarteners have both doses of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine, commonly called the MMR vaccine. In some parts of the state, the rate is much lower, coming in below 50 percent.

That’s a problem because of how contagious measles is.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Malia Jones is a public health researcher and assistant professor in the Department of Community and Environmental Sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” that even an 85 percent vaccination rate, which might sound high, is not enough when it comes to measles.

“We need really, really high vaccine coverage in order to protect a community from a measles outbreak,” Jones said. “It is the most infectious disease on Earth. Nearly everyone who is exposed to measles and has not been vaccinated will get it.”

“For measles, we need something like 95 to 98 percent of all people to be vaccinated in order to protect us from an outbreak,” she continued. In Wisconsin, “we’re well below that in many, many settings.”

In public health, infectious diseases have what’s called a “reproductive number” that represents how many people one sick person will infect on average. For context, the original strain of the virus that causes COVID-19 had a reproductive number of three. Measles has a reproductive number between 12 and 18, which surpasses diseases such as chickenpox and mumps, too.

“That means for every infection, it can spread to 12 to 18 more people who are unvaccinated,” Jones said. “And if you think about a school setting … it’s very easy to get 12 or 18 kids in a room, and if a lot of them are unvaccinated, you’re going to see very rapid spread.”

“I would even go so far as to say that it’s just a matter of time before Wisconsin has an outbreak,” she added.

For Wisconsin counties with low vaccination rates, the risk of measles is high

Melissa Geach is health officer for the Iron County Health Department in northern Wisconsin, a county that saw measles vaccination rates of 2 year olds between 2013 and 2023 drop from 93.3 to 72.5 percent.

Geach attributes this to barriers like distance, with some patients driving up to an hour to their nearest clinic.

“Families in rural areas may have to travel a long distance or they struggle to get timely appointments,” Geach said. “Competing priorities like food insecurity, job loss, unstable housing and lack of paid time off can make it difficult for parents to prioritize vaccines. And for some, measles just doesn’t feel like an urgent threat because they’ve never seen a case firsthand.”

Geach said that measles vaccination rates tend to go up once children reach school age because of Wisconsin’s immunization requirements for students in public school. But the state also has one of the most lenient exemption policies in the country, so it’s relatively easy for parents to opt out even as their child enters kindergarten.

To bridge this gap, Geach said the county has several public outreach efforts to educate parents about vaccines and give them reminders about immunization schedules. This is especially important as misinformation about vaccines continues to spread.

“We have provided guidance for people who have chosen to delay vaccines and ultimately change their mind, and I want people to know … it’s always OK to change your mind and vaccinate your children,” Geach said. “Vaccination is one of the safest and most effective ways we can keep our kids healthy while they’re growing up.”

Even with some parents reversing course and getting their child up to date on vaccines, the overall low rate of vaccination in Wisconsin makes communities like Iron County vulnerable to a measles outbreak.

“It’s really all hands on deck for our small department if a case were to come to Wisconsin,” Geach said.

The real costs of measles

Measles can be very dangerous. In more serious cases, measles can lead to encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain that can cause brain damage or even death.

Even with common cases of the measles, it’s not unusual for children to have suppressed immune systems for several years afterward, making them “much more vulnerable to all the other stuff that is going around” like the flu, Jones said.

“And so you actually see elevated rates of death from all infectious causes after a measles outbreak,” she said.

One big misconception that some people have about MMR vaccines is that they can cause autism in children. However, this has been thoroughly debunked by the medical community.

“There aren’t a ton of things that I would come on live radio and say ‘We know for sure,’” Jones said. “But this has been studied very thoroughly, and so this is one that we really are very confident about.”

Protecting yourself against measles as an adult

For adults who can’t access their immunization records and aren’t sure if they have the measles vaccine, Jones outlined a few options.

First, you can have your immunity against measles tested with a simple blood test called a titer test. This test might not be covered by all health insurance plans, so it’s a good idea to check before scheduling an appointment.

Otherwise, Jones said it’s perfectly safe for people who aren’t sure about their vaccination status to simply get vaccinated for measles.

She recommends one or both of these routes for people who could become pregnant soon, since the measles shot is a live vaccine and therefore not recommended during pregnancy.

“Measles outbreaks are becoming more and more common, and an infection during pregnancy is very dangerous,” Jones said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.