A confirmed case of mumps in Clark County, which has one of the state’s lowest rates of vaccination against measles, mumps, and rubella, or MMR, has public health officials on alert.

Dr. Jonathan Temte, a professor of family medicine and the associate dean of Public Health and Community Engagement for the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, spoke with WPR’s Shereen Siewert to explain the symptoms of mumps and the broader implications involved.

He also discussed the factors that play a role in Clark County’s MMR vaccination rate, the second-lowest in Wisconsin.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Temte said that vaccine hesitancy, access challenges, and mistrust of the medical system are common barriers to improving vaccination rates in rural areas like Clark County.

“First and foremost, I think there’s access to care issues,” Temte told Siewert on Morning Edition. “To get vaccines very, very close to home, we have to have sufficient pediatricians and family physicians. There can also be increased hesitation in rural areas, sometimes because of that lack of availability of trusted clinical practices.”

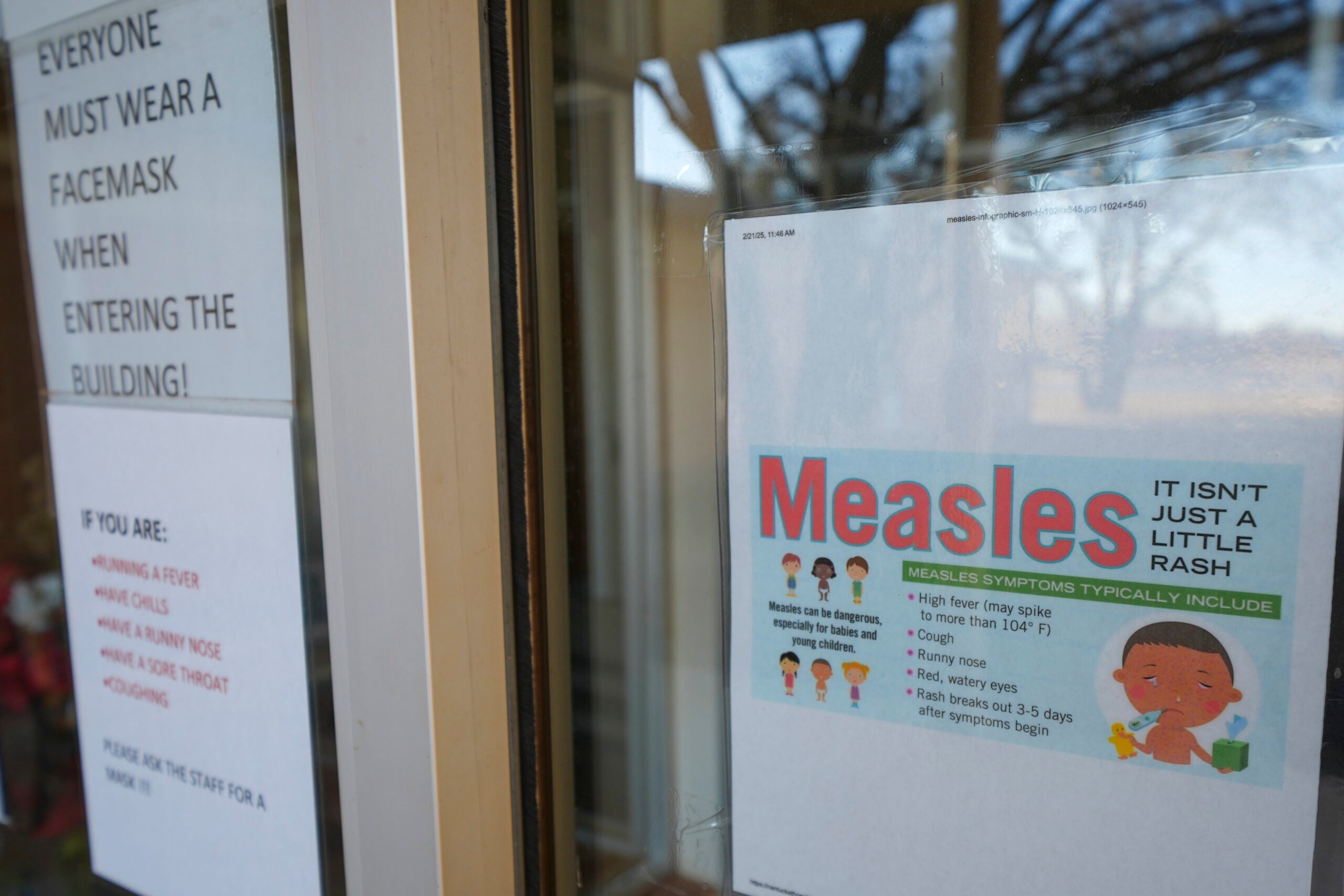

Mumps begins with flu-like symptoms including fever, muscle aches, pain in the front of the neck and trouble chewing. Complications can be more severe, ranging from encephalitis to deafness.

The following interview was edited for brevity and clarity.

Shereen Siewert: How common are mumps cases?

Dr. Jonathan Temte: Every year in the United States, we see anywhere from 1,000 to 4,000 cases, and those are just those that are identified and reported. This is a disease that oftentimes is asymptomatic or has very nonspecific symptoms. So, we really don’t know.

But what we do know is that we see a whole lot less than we used to before we had a safe and effective vaccine.

SS: Why do cases of mumps persist despite widespread vaccination programs?

JT: There are two good reasons. No. 1, we are lagging in uptake of the vaccine for this virus. The vaccine is packaged together with measles and rubella protection. And unfortunately, across the country and here in Wisconsin, we’ve been seeing the rates of uptake of this vaccine slowly drop off.

The second reason is that of the three components of this vaccine, the mumps component is the least effective. It’s still between 80 and 90 percent effective in preventing cases, but it’s not 100 percent.

Keeping up with the vaccine and making sure that people have not only one, but two doses is really important.

SS: Who is most at risk of contracting mumps?

JT: What we’ve seen historically is college-age people, young people who are congregated together, but we also have people across the age spectrum. Looking back decades it was the younger individuals who probably saw more significant effects of mumps. Those effects can include nervous system issues, inflammation of the testicles and ovaries and things like that.

SS: Do any environmental or social factors in rural areas like Clark County play a role in the spread of mumps?

JT: One concern I have is that of all counties in Wisconsin, Clark County has the second lowest rate of coverage for the MMR vaccine. The door is open for potential spread, especially in counties that have low vaccination rates.

In Wisconsin, we tend to find a pattern between lower coverage in rural areas and higher coverage in urban areas. There are many, many reasons for this.

SS: What are the signs and symptoms of mumps and how are they differentiated from other illnesses with similar presentations?

JT: About 20 percent of cases can be asymptomatic. Maybe double that, between 40 and 50 percent, would be very nonspecific with muscle aches, tiredness, headache, low grade fever and some respiratory symptoms.

But about 30 to 40 percent of the time, the classic symptom we look for is what we call chipmunk cheeks. That’s the big swelling of the salivary glands in our cheeks, where it looks like someone has a big piece of tobacco stuck in their cheek. It really sticks out there, and that’s the characteristic we see that makes us more likely to test for mumps.

But there is one caveat, and that is that influenzas can cause that swelling as well. High level laboratory techniques, molecular methods called polymerase chain reaction tests, are the ones that can really define whether we are seeing mumps. There are many more cases in the community that we don’t detect.

Fortunately, today we see very few of those long-term problems that mumps can cause. Before we had vaccines, the things we were most concerned with were encephalitis and deafness. We rarely see that now.

More commonly, we see inflammation of the testicles and ovaries, but few end up with any long-term consequences such as infertility. In terms of swelling of the salivary glands, those symptoms come and go but don’t leave any long-term consequences.

SS: What comes next? What steps should public health officials and the community as a whole take to prevent further spread of mumps today?

JT: A single case is not going to raise the alarm, but when we have a legitimate outbreak, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have recommendations to provide a third dose of the MMR vaccine.

Usually for most of us two doses are sufficient, but in response to a mumps outbreak we can use that MMR vaccine to help contain it.

I want to really emphasize that the vaccine is not only very effective, but it’s very, very safe from a public health standpoint. Trying to improve our rates of vaccine coverage across the state and country is very, very important.

If you have an idea about something in central Wisconsin you think we should talk about on “Morning Edition,” send it to us at central@wpr.org.