When Lay’s chips used the slogan “no one can eat just one” in a commercial, the company meant to convey just how good the product tastes. The chips are so delicious, even someone with the discipline of a professional athlete lacks the strength to stop at just one.

But new research published in the British Medical Journal finds that when it comes to certain foods, willpower doesn’t matter much — even if you’re Canadian hockey great Mark Messier.

Ultra-processed foods may disrupt the body’s signals of feeling full, its ability to absorb nutrients and digestion. Those disruptions can make it difficult to know when to stop eating. That may be why ultra-processed foods are correlated with over 30 health problems, including Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, cancers and obesity.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Beth Olson, an associate professor of nutritional sciences in the Department of Agricultural and Life Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, recently spoke to WPR’s “Central Time” about how to identify ultra-processed foods and make healthier choices.

The following has been edited for brevity and clarity.

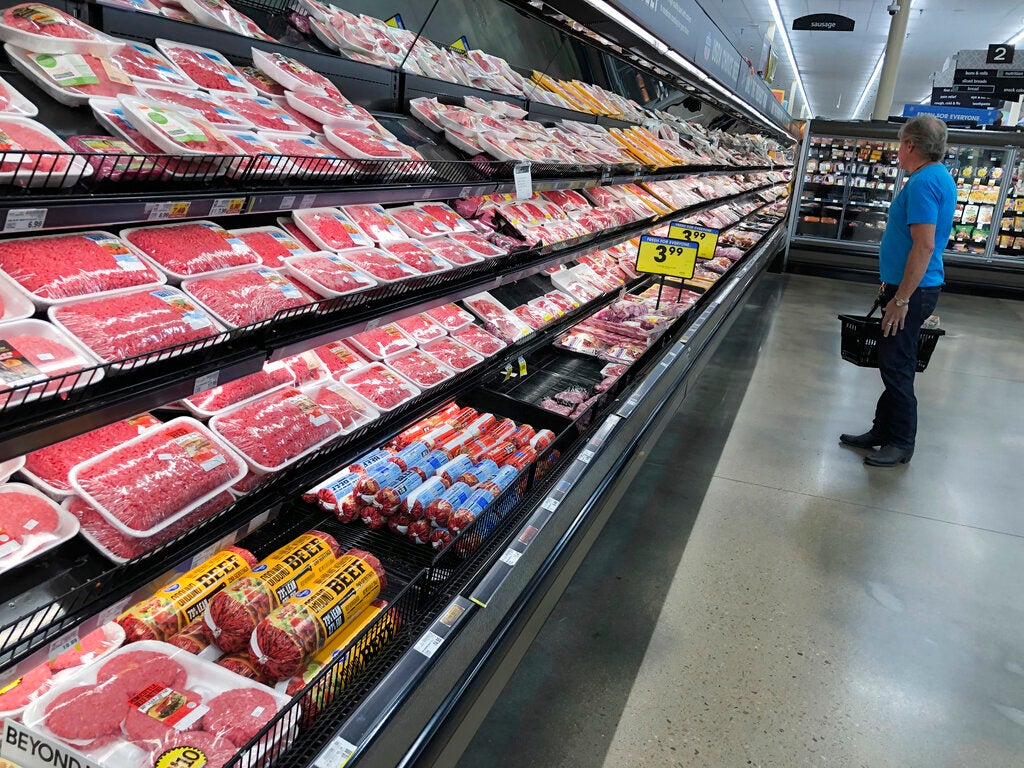

Rob Ferrett: What are rules of thumb for when we’re at grocery stores and restaurants trying to figure out whether something is too processed to be healthy?

Beth Olson: We can use a couple of things. One is common sense. When you’re in the produce aisle, and you’re looking at the fruits and the vegetables, those are going to be good foods for you. Shop around the perimeter of the store.

The other thing is to look at labels. When you’re in the middle of the store and picking up a can or a box or a frozen package, look at the label and say, “How much fiber does this have? What’s the ingredient listing? Does it list whole wheat, or does it list a kind of refined grain?”

RF: What are the kinds of foods where we’re most likely to run into ultra-processing?

BO: Snack categories or treat categories — pretty much everything in the aisle that has chips and crackers and foods like that — the candy aisle and baked goods. All of those foods are certainly going to fall into that ultra-processed category.

RF: What is it about these ultra-processed foods that may be linked with bad health outcomes down the road? Is it bad stuff in the food itself, or is it that we’re eating ultra-processed foods instead of the good stuff?

BO: It’s probably both. You’re eating foods that are probably higher in fat … foods that may not have ingredients that we need for our guts to be healthy.

Part of it is that we’re crowding out all the foods that we recommend people eat. If people actually followed the dietary guidelines and ate the foods that are recommended, they just wouldn’t have as much room left in their diet for the ultra-processed foods.

RF: We hear about food deserts where people don’t have access to fresh produce, people without enough money or enough time to prepare foods. What can we do to help in those situations?

BO: We can work in communities to have better stores in our local neighborhoods. We can provide incentives for purchasing healthier foods or making them accessible to those who don’t have as much money — having healthy foods available in our schools, for instance, so that any kid coming to school can have a healthy meal.

We can also do education. Working with people on … how do you make choices among those food items that are best? How do you make choices with the money that you do have? How do you read labels to maximize the nutrients you get for the dollars you spend?

RF: Some of these ultra-processed foods are processed to be “hyper-palatable,” meaning they make us want to eat them and keep on eating them. Is this actually leading us to eat more calories and more salt, sugar and fat?

BO: Food manufacturers know how to make food taste good. That’s their business. It will contribute to us eating a bit more than we should.

It also comes from how we’re brought up and what we get used to. If we’re brought up with these foods, then that’s what we prefer. If we can help families choose other foods for their littlest kids so that they grow up exposed to fruits and vegetables and whole grains, we can help people develop some preference for them.

RF: I’ve seen this argument that any food your grandparents wouldn’t recognize or make is probably ultra-processed. What do you think about that as a rule of thumb?

BO: Most researchers and nutritionists see a difference between processed and ultra-processed. Indeed, much of the food we eat now compared to what our grandmothers got in their gardens is processed. But it doesn’t mean that it’s all unhealthy.

There are plenty of healthful options that do come in boxes or cans or in the frozen food aisle: frozen or canned fruits and vegetables, and whole grain breads, for example.

I think it’s a little too simple to say that if your grandmother didn’t prepare it, it’s not healthy.

RF: I eat breakfast cereal. I’ve eaten it my whole life. I’ve probably eaten a disturbing amount. Generally, my rule is I look at the label, and if it has four grams of fiber or more, that makes me think, there’s some real food in here. Am I fooling myself?

BO: That’s a great rule of thumb. One of the ways I talk to people about choosing foods is, if that’s what you want to eat … pick up a selection of them, and look at the labels and compare. Are you picking a food with more fiber and more whole grains in it if you’re looking at bread or breakfast cereal?

If you’re buying a soup, does it have more fiber, does it have more vegetables, does it have a leaner meat in it, or does it have more added fat or sugar? Pick the soup, but look among the soups and make the best choice among those.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.