An announcement from the National Institutes of Health earlier this month said the agency would slash support for indirect research costs paid to universities, medical centers and other grant recipients.

The change could leave research institutions like the University of Wisconsin-Madison scrambling for millions of dollars from other sources to support labs, students and staff.

Wisconsin has joined 21 other states suing to stop the cuts. The policy is currently blocked by a federal judge, who is considering how to rule after hearing arguments in the case last Friday.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Jo Handelsman previously served as a science advisor to President Barack Obama as the associate director for science at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. Now, as the director of the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, Handelsman has been keeping a close eye on how federal funding cuts would affect medical research at her institute and UW-Madison as a whole.

“This is just a travesty to biomedical research at the most basic, fundamental level, (and to) the applications that people are counting on,” Handelsman said in an interview with WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

She talked with host Kate Archer Kent about the possible consequences of proposed NIH funding cuts.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kate Archer Kent: How many projects and labs at the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery are currently receiving some aspect of funds through an NIH grant?

Jo Haldelsman: In the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, which is just a small part of the University of Wisconsin, there are several dozen NIH grants, and those are absolutely essential to what we do. On campus, there are 938 grants from the NIH active right now. It’s our largest source of research support, both at our institute and with the university generally.

KAK: What kinds of research are these NIH grants supporting?

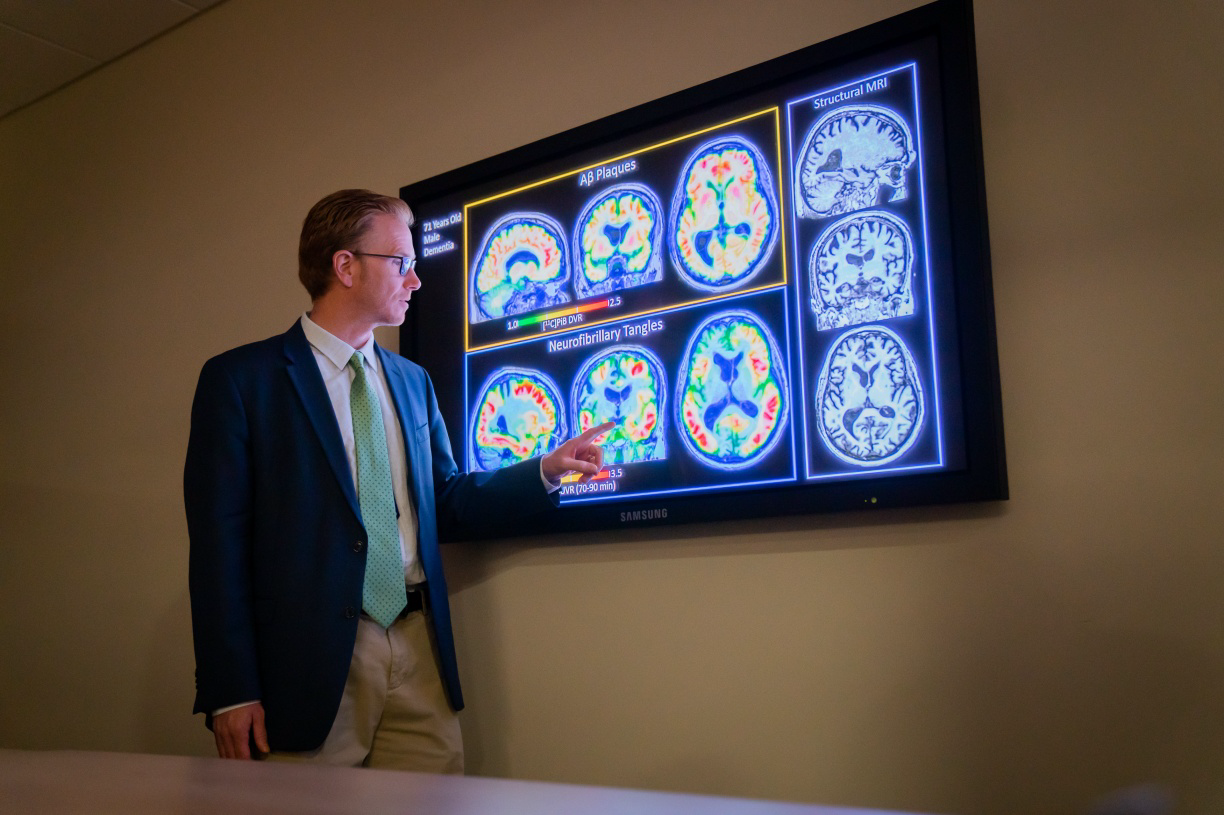

JH: There’s an enormous range. Some of them have very near-term patient effects, and some of them are very long-term — finding very basic discoveries that will lead to long-term work toward treatments.

For example, in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, there’s a project moving toward correcting a gene that causes blindness in children and adults. It involves a very innovative delivery process using nanoparticles — really tiny particles — to deliver the gene editing tools very precisely. That’s the kind of thing that you can’t do on small grants or from any other agency besides the National Institutes for Health.

There are also patient trials. These are already clinical trials, and it’s really unsafe for participants if the trial has to be stopped suddenly in some cases. And it’s certainly wasteful if you start a trial and you’ve collected data and you’ve recruited all these willing participants, and then all of a sudden that trial is halted.

KAK: At the heart of this financial disruption is indirect costs of conducting research, which would be limited to 15 percent of grants. What do these overhead costs include?

JH: There are two different ways of supporting research, and both are absolutely necessary. The direct costs are the ones that most people think of: supporting graduate students or research staff, or buying equipment.

The indirect costs are more at an institutional level. You can’t just start a lab in a vacuum. You have to have a large infrastructure around that, and that involves everything from electricity to building costs to maintenance of the buildings, and all of the staff that support those grants. That can be everything from financial management to biological safety to human safety and security and police force.

There are many, many aspects of the university that wouldn’t exist or maybe be as large as they are if we weren’t doing research and these large research projects. That was how the indirect cost for facilities and administration was originally designed to meet the needs that you reimburse at a university-wide level, rather than project by project.

KAK: The NIH memo says this cap would bring the National Institutes of Health into line with the maximum indirect cost rates allowed by private foundations. How do you view that comparison?

JH: Foundations are a pretty small percentage of the overall research costs at the university. So many universities have decided to accept those funds from foundations, even though the overhead costs are lower. … Other universities say, “We just can’t take the money.” It’s just too expensive to subsidize the research to that extent.

Even at the high (facilities and administration) reimbursement rates for NIH, the university is still covering half of those indirect costs. That was the original deal 70 years ago, was that universities and federal agencies would split those costs.

KAK: Perhaps the NIH is just exploring ways to reshape research processes, to make them more efficient. Is that a valid argument?

JH: I don’t think so, because a lot of the activities that are supported by these indirect costs are required by the federal government — certain kinds of auditing and training for our staff to keep them safe. You can’t get away with not doing those things, because that would be against federal regulations. So they’re going to have to completely change the regulations around science and what we’re required to do.

And frankly, we don’t want to stop training staff to be safe in the laboratory. We’ve moved toward many of these regulations over many decades of research learning the hard way.

KAK: Could these funding caps result in layoffs?

JH: Absolutely. No question about it. The university would lose $65 million of indirect costs, and probably more than half of that goes to salaries. So I don’t know what we would do to compensate for that loss. We certainly don’t have enough state money. Our tuition can’t cover it. There just aren’t other sources, and so I can’t imagine we could get through this without layoffs.