When the U.S. government closed Green Lake Park in 2015 citing budget cuts, nearby residents lost access to a local park, the lake within it and a historically protected structure.

In the Town of Mountain, in Oconto County, the park had been a staple for over 80 years, said Brenda Carey-Mielke, a town board supervisor. The park’s closure in 2015 “hit the community really hard,” she said.

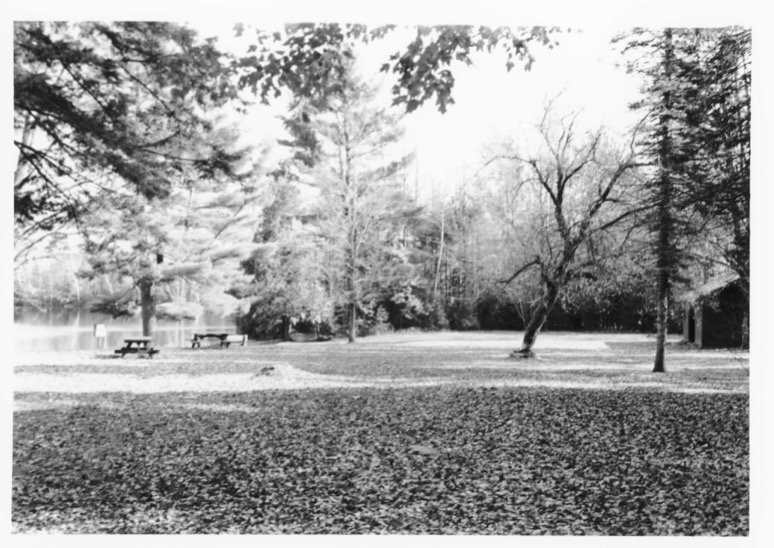

“It’s just nice. It’s picturesque,” Carey-Mielke told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “It has not been polluted — minimal phosphates. It’s got a sandy beach, sandy waters. It’s just beautiful.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

When Carey-Mielke was elected president of the Mountain Historical Society, resident Barb Palmer approached her with a conviction to reopen the park. Palmer said she had learned to swim in Green Lake. She considers the park a community treasure.

At first, Carey-Mielke was at a loss. A prior effort to reopen the park had been “shot down” by the U.S. Forest Service, she said.

“(Advocates) were told ‘Absolutely not. That park is never reopening. We’re not going to enter into any agreement with anybody on it,’” Carey-Mielke said.

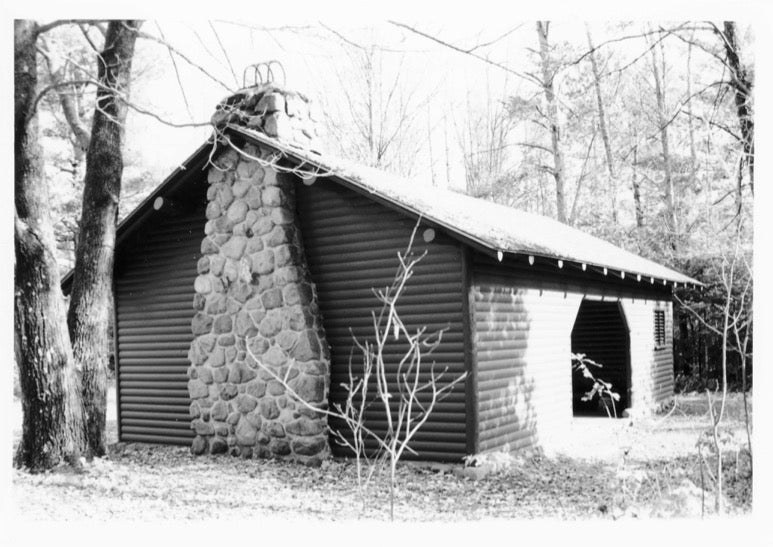

But Palmer and Carey-Mielke found a key piece of information. A historical structure in Green Lake Park has been on the National Registry of Historic Places since 1996. The Mountain Historical Society had been charged by the Secretary of the Interior to maintain and preserve the site.

The shelter in Green Lake Park was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the late 1930s as a “warming place” for the corps and their families. It was placed on the national registry because “it’s culturally significant to our community. It’s a part of our heritage and our roots,” Carey-Mielke said.

Without access to the structure, the Mountain Historical Society couldn’t uphold its duty to protect the shelter. When presented this information, lawmakers agreed the park should reopen.

“They literally rewrote the federal policy on the closing of these parks to allow nonprofits like Mountain Historical Society to enter into an intergovernmental agreement with the U.S. Forest Service,” Carey-Mielke said.

The Mountain Historical Society now has a 25-year renewable lease to restore, protect and preserve the park for the community. Having been closed for almost a decade, the park was in no shape to open to the public, Carey-Mielke said.

“We decided that Saturdays were going to be community park cleanup days,” Carey-Mielke said. “The first day we had 48 volunteers. People showed up with trucks, trailers, chainsaws, front motors, bobcats, rakes, shovels. Whatever they could do, they brought to help.”

The park is now set to open to the public on Saturday, May 25.

“I don’t know how we could have afforded to have this park cleaned up the way we did without the members of the community coming forward and stepping up,” Carey-Mielke said. “We are at approximately $24,000 of in-kind contributions and labor.”

Palmer is excited to go back to the lake she spent most of her life swimming in. She hopes the next generation embraces this part of Mountain’s culture.

“I grew up here, left for 40 years to make a living and retired back here in 1998,” Palmer said. “It draws every one back who has been here.”

“That’s a good way of putting it,” Carey-Mielke added. “People come back home.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.