NOTREES, Texas — One of the boldest, most controversial experiments in fighting climate change is taking shape in a dirt patch in West Texas.

In a couple of years, giant fans will start whirring at the Stratos facility near Notrees, a town in the wind-swept Permian Basin of Texas.

It will capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and inject it underground, in a process called direct air capture.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The logic is clear. Humans have been releasing CO2 into the air for many decades. Removing some of that carbon dioxide could be a key way to reverse the impact of those accumulating emissions.

And direct air capture is one way to do that — a vital one, proponents argue.

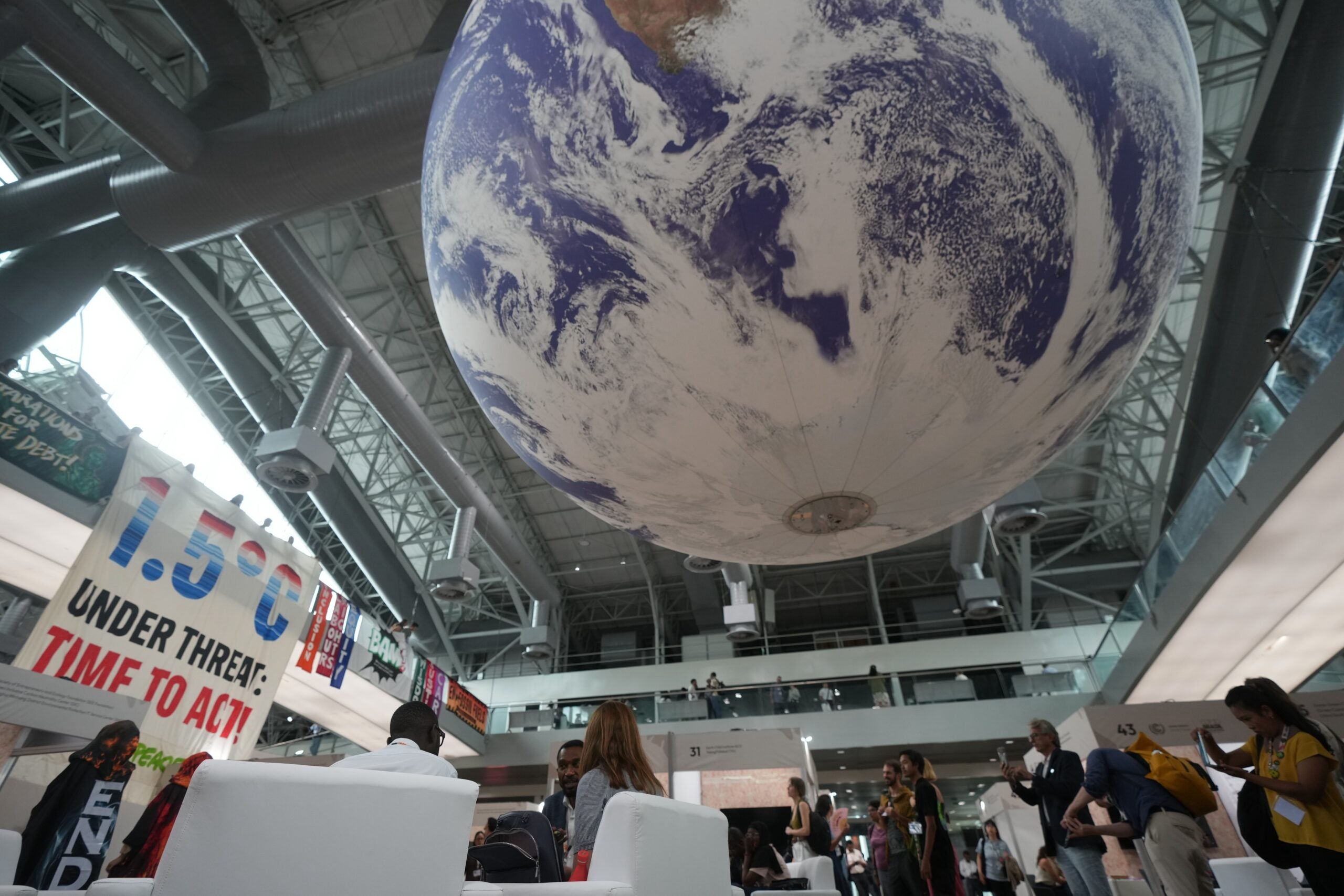

At this year’s annual United Nations climate talks in Dubai, the world agreed to transition away from fossil fuels to slash carbon emissions and stabilize climate change.

But experts say that even in the best case scenario, the world will need technologies like direct air capture to catch up to climate goals. And the more the world falls behind in slashing emissions, the more this expensive, energy-intensive technology may be required.

The Stratos plant — being built in the midst of oil fields — is playing a key role in scaling up the technology, which is not fully proven yet. Once it’s up and running, the billion-dollar facility will be 100 times bigger than any direct air capture plant ever built — and yet, even if it works perfectly, it will take a year to remove less than 10 minutes’ worth of global emissions.

And the company behind it is not a university, or a Silicon Valley startup. It is, in fact, an oil company: Occidental Petroleum, or Oxy for short, an American producer that’s placing a bet on this technology.

Why? Well, there’s money, naturally. Companies looking to offset their emissions are willing to pay to get carbon removed from the atmosphere and stored underground. The government is putting billions of dollars into this technology. And Occidental has the right expertise to scale this technology up and bring costs down, thanks to similarities between direct air capture and oil production.

But there’s another reason. And it’s no secret.

The company intends to use the technology to do what it does best: to extract more oil, thus helping prolong the life of the same fossil fuels that climate experts say need to be wound down.

It’s a win-win, from an oil business point of view. Oxy can profit off selling oil, while simultaneously profiting off capturing emissions.

And by combining the two, the company even thinks it can market “net-zero” oil — because the carbon captured while producing the oil “cancels out” the CO2 released by burning it. Oxy’s CEO, Vicki Hollub, has been consistently clear about her hope for the technology.

“If it’s produced in the way that I’m talking about, there’s no reason not to produce oil and gas forever,” Hollub told NPR.

It’s the kind of comment that makes climate advocates scream, and even some supporters of Oxy wince. Because the question it raises is obvious.

Is direct air capture a way to save the world? Or a way to save the oil industry?

“Something extraordinary”

Occidental’s ambitions are being charted by Hollub, a 63-year-old oil executive with the backing of Warren Buffett and a history of making bold bets. Starting as an engineer, she rose through the ranks at Oxy to become its CEO in 2016 — a rare female leader in the mostly all-boys club of the Texas oil fields.

Her climate stance, too, is unusual. Occidental has set a net-zero target that includes the emissions from the oil it sells, a first for a big U.S. oil company.

Sucking carbon from the sky and injecting it underground is key to that vision.

This spring, Occidental held a groundbreaking celebration for the Stratos plant in West Texas. Since then, the company has announced another project, in South Texas, that’s getting massive support from the federal government. Ultimately, the company plans to build up to 135 of the giant machines.

As the wind rattled a big white tent at the Stratos groundbreaking back in April, Hollub took the stage.

“Sometimes history puts you in the right place at the right time with the tools you need to do something extraordinary,” Hollub said, in her careful, precise speaking manner. “And together we, with our partners and supporters, have seized this moment to start the deployment of large-scale direct air capture around the world.”

Some climate advocates agree that Oxy’s doing something extraordinary for the planet. Others, however, are raising alarms about why.

The International Energy Agency calculates that the world needs to remove 80 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year through direct air capture by 2030, and more than 1 billion metric tons per year by 2050, to meet the world’s goal of holding warming beneath 1.5 degrees Celsius.

That assumes the world also cuts emissions sharply and restores vast expanses of forests and wetlands, which also remove carbon dioxide from the air.

Getting to that scenario would require about a thousand giant direct air capture plants twice the size of Stratos, each capturing a million metric tons per year

But the slower the world acts, the bigger the numbers get.

The IEA described one possible future where cutting emissions more slowly would mean that the world would need to capture more than 3.3 billion metric tons per year from the atmosphere. Some projections call for much more than that.

And who would provide this service? A number of startups, many funded by tech giants with an interest in carbon removal, are chasing various technological solutions.

Some combine natural processes and high-tech ones, while others rely on chemistry and materials science.

But few have the financial resources and technological expertise of Occidental, which is planning to invest billions in direct air capture.

The oil giant has been working on the technology for years; it invested in Carbon Engineering, a direct air capture startup, in 2019 and bought it outright this year for $1.1 billion.

Carbon Engineering’s approach to direct air capture is complex.

The concentration of CO2 in the air is very low, in absolute terms — around 420 parts per million.

Getting the carbon is like trying to find needles in a haystack. Direct air capture is like a magnet that draws the needles out of the hay. Then you dislodge the needles from the magnet and stash them somewhere for safekeeping.

In practical terms, it means using large fans to push air over a liquid that absorbs carbon dioxide. Next, the company removes the CO2 from the liquid in the form of pellets, then heats them up to release pure CO2.

The technology to pull carbon dioxide from the air is not new. It’s been around since the 1950s, and companies like Carbon Engineering have been pitching it as a climate solution for more than a decade. The challenge was doing it at a massive scale, and for a reasonable cost.

Dan Friedmann, the CEO of Carbon Engineering, the company Oxy bought, is used to people questioning why a climate startup would pair up with an oil giant.

He has a simple answer.

“We needed somebody that could build billion-dollar plants. Oxy can,” Friedmann told NPR in an interview earlier this year. “We needed a company that was willing to go into this business with their top people, their money — and frankly, to this day, I can’t find another one other than Oxy.”

Friedmann also emphasized the challenge of putting carbon dioxide underground after it’s captured.

“The only people in the world that know how to do that are oil companies, and Oxy is the world expert,” Friedmann says.

That’s because Oxy injects a lot of carbon dioxide into the earth already as part of its oil production.

Occidental has a clear plan: Make more oil

When you first drill a well, oil gushes out. Over time it slows to a trickle. But most of the oil remains underground. Even after companies inject water underground to repressurize the well and squeeze out more oil, some oil remains stuck on the rocks.

Geologist Bob Trentham at the University of Texas, Permian Basin in West Texas compares the process of extracting oil to changing the oil in your car — “which nobody does anymore,” Trentham notes wryly — and getting oil on your hands. “You can use a rag to get most of it off, but it’s going to stay there until you use a detergent,” he says.

Carbon dioxide is “kind of like Mr. Clean,” Trentham says. “It gets in there and it scrubs some of the oil off the pores, and produces more oil.” Companies have been using CO2 to coax more oil out of aging wells for decades.

It’s also possible to inject CO2 deep underground just to store it, with no oil production involved.

Companies will pay for credit for the carbon that’s removed so that they can offset emissions from their ongoing or previous use of fossil fuels. Oxy will sell this service, too. Airbus, for instance, has agreed to buy 400,000 metric tons of these carbon removal credits from Oxy.

But Hollub has said she’d prefer to use the captured carbon dioxide in oil production. Oxy would capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, inject it into an oil field, and then argue that the CO2 used to make the oil cancels out the CO2 released by burning that oil.

If she can prove the math checks out, Hollub argues that this “net-zero” oil would allow the world to keep using oil and natural gas instead of transitioning away from it.

And not just in aviation and other industries that are hard to decarbonize: Hollub told NPR she believes “net-zero” oil could offset the need to switch to electric vehicles and allow the internal combustion engine to remain in use.

Some rivals in the direct air capture industry are trying very hard to distance themselves from this argument.

“We want to just make sure that we’re never gonna even come close to it,” says Carlos Härtel, the chief technology officer at direct air capture company Climeworks. His company exclusively injects carbon underground to store it, without also making oil and gas.

But Oxy actually sees benefits for the oil and gas industry even if the captured carbon isn’t used for oil production. Just the ability to purchase “carbon removal credits” might persuade some companies and countries that they don’t need to move as quickly to reduce their use of oil.

Climate experts, however, say the world needs to scale up direct air capture, while also massively reducing the use of oil and gas, and reject arguments that the technology can actually be used to justify more oil production.

Partly that’s because the world releases a simply mind-boggling amount of carbon dioxide.

The Stratos plant may be the biggest of its kind, but even when run perfectly, it would end up taking a full year to capture what the world releases in 7 1/2 minutes today.

Pulling carbon dioxide out of the sky the way Oxy plans to do also requires enormous quantities of energy.

And carbon removal has simply never been done at the scale Oxy envisions. In a report this fall, the International Energy Agency warned that relying on this kind of technology to keep global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius is unacceptably risky because if technologies fail to deliver, there’s no backup option.

“Removing carbon from the atmosphere is costly and uncertain,” Fatih Birol, the head of the IEA, said this fall. “We must do everything possible to stop putting it there in the first place.”

Some climate advocates have a more profound distrust of this technology. They see it not just as risky, but as a con: a way to distract and delay climate action altogether.

In West Texas, a few days after the Stratos groundbreaking, an independent oilman gave an unusually clear example of what environmentalists are afraid of.

Waymon Pitchford of Midland, Texas, thinks the idea of sucking carbon out of the atmosphere is as absurd as “draining the ocean with a straw.”

But, he says, the idea of it could “shut some people up” — specifically, people who keep talking about the need to cut oil consumption.

“So let’s go run out there and build all these plants we can build to shut up whoever we need to shut up,” he said.

The U.S. is pouring billions into direct air capture

As the debate roars over the true purpose of direct air capture, a lot of money continues to pour into the industry, including a lot of American taxpayer funds.

The federal government has put $1.2 billion toward two direct air capture plants, one of which is Occidental Petroleum’s planned facility in South Texas. It’s spending many billions more in tax incentives for the technology, and Oxy is taking advantage of that as it seeks to make a profit on its direct air capture investments.

The government has also announced a smaller pilot program to purchase carbon capture credits directly.

The government push, combined with private investments from companies including Oxy, means direct air capture is attracting tens of billions of dollars.

But direct air capture has not proven it can scale up the way supporters envision. There are economic, technical, legal, political and practical challenges.

Some investors and analysts view Oxy’s direct air capture projects as a hedge — sort of like an insurance policy. If oil demand stays high, Oxy will happily sell the world oil; if it drops, Oxy can pivot to carbon removal.

Alternately, direct air capture could be a way to extend the life of Oxy’s highly profitable oil business. Not an insurance policy in case oil demand drops, but an effort to keep it high and make oil more profitable for longer.

An Occidental executive told NPR both those interpretations are “incomplete,” emphasizing that direct air capture could be a revenue stream in its own right and provide a new way to monetize Oxy’s existing skills and resources.

But Hollub’s public statements about extending the life of oil have fueled the mounting tensions over whether the direct air technology is being used to delay a transition from oil.

“Whether it’s good or bad depends on the how,” says Natasha Vidangos, the senior director for climate innovation and technology at the Environmental Defense Fund.

That, in turn, will decide whether direct air capture, if it can even be scaled up, is actually helpful for the fight against climate change — or is just an excuse to stop trying.

9(MDAyMjQ1NTA4MDEyMjU5MTk3OTdlZmMzMQ004))

© Copyright 2025 by NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.9(MDAyMjQ1NTA4MDEyMjU5MTk3OTdlZmMzMQ004))