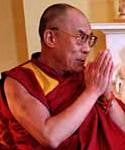

In March 2008, Amy Yee — then a Delhi correspondent for the Financial Times — attended a press conference given by the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, India, where he had established a government in exile nearly 50 years before.

Earlier that month, protests marking the 49th anniversary of the 1959 Tibetan uprising against Chinese rule had led to crackdowns, with more 100 Tibetans killed in clashes with security forces.

Yee was surprised when the Dalai Lama singled her out from the crowd of reporters. He asked if she was Chinese. Yee, whose parents are from Hong Kong, hesitated before answering that she is American. After surprising her further with a large bear hug, the Dalai Lama commanded Yee to “tell them” — meaning the Chinese — that only talks between Tibet and China would resolve the crisis.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

That first visit to Dharamsala sparked Yee’s interest in the lives of Tibetan refugees. Since the Chinese invasion of Tibet in the 1950s, more than 100,000 Tibetans have fled the country. A large majority live in Dharamsala, which has become home to the government in exile — and has also become a spiritual home.

Yee moved to Dharamsala in 2009 and for a year followed the lives of exiled Tibetans, from basketball-playing monks to former political prisoners to a middle-class couple who gave up everything and fled there rather than risk arrest for the illegal act of photocopying fliers stating, “Long Live the Dalai Lama.”

Most of Yee’s initial reporting focused on the community in Dharamsala. But as the years went on, some of Yee’s contacts moved to places in other parts of the world — Australia, Belgium, New York. She stayed connected. The result is now a book — Far From the Rooftop of the World: Travels Among Tibetan Refugees on Four Continents — a mix of reportage and travelogue.

In a phone interview, Yee discussed what she witnessed and the resulting book. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to write about Tibetan exiles?

I had been in Tibet before when I was just backpacking, after teaching in China for two years in the late 1990s. And in Tibet itself, you cannot even have a photo of the Dalai Lama. You can’t have a Tibetan flag, or even a photocopy of it. You can be arrested for that. And worse. So we were seeing protests happening in Tibet. Meanwhile, in this parallel universe [in Dharamsala], this haven of Tibet in exile, you had people out on the streets demonstrating, protesting. There were thousands of people marching in the streets of Dharamsala peacefully, carrying photos of the Dalai Lama, the Tibetan flag, all kinds of banners and signs. So, it really struck me that this was what Tibetan identity and culture could be like, if it could flourish freely without repression. I mean, literally on the other side, in Tibet, we were seeing people getting shot for doing something like that.

How was it for you as a person of Chinese origin connecting with exiled Tibetans? Against the backdrop of Chinese political repression against the Tibetan population, were you worried about how you would be received?

I was never greeted with any hostility. I was always received warmly and welcomed. People would sometimes come up to me, unbidden, and speak to me in Mandarin, which I had learned in college. That totally surprised me. And I think sometimes they were a little disappointed that I was an American.

Why is there such an interest in Chinese-speaking visitors or in connecting with the Chinese?

You could tell from the Dalai Lama’s approach towards me, he encourages good relationships with Chinese people. And he is always reaching out to who he calls, “Chinese brothers and sisters.” He gives special teachings and audiences to ethnically Chinese people, whether from China, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, etc. The filmmaker Tenzing Sonam followed the Dalai Lama around the world in 2008 for his documentary The Sun Behind the Clouds. Tenzing told me the Dalai Lama was almost obsessive about meeting Chinese people wherever he went. That might seem counterintuitive, but that’s very high on the agenda. And I think it’s probably a form of soft diplomacy.

The Dalai Lama said, ‘I still have faith in Chinese people.’ I think that is an extraordinary thing to say. He said, ‘My faith in the Chinese government is getting thinner and thinner. But I still have faith in Chinese people.’

It’s pretty extraordinary, given especially at that time in March 2008, the tensions were running so high. And he was still encouraging good relationships because he — and then many Tibetans — can distinguish between a regular Chinese person and the actions of the government of China.

You wrote about an event commemorating the 1959 Tibetan Uprising and a carnival game that featured a wooden signboard with a caricature of the Chinese president Hu Jintao. Attendees took turns attempting to throw a shoe through a gaping hole representing Hu’s mouth. You wrote that, “while the Dalai Lama espouses nonviolence as a spiritual leader, most Tibetans are regular human beings and humans express frustration, anxiety, anger and grief in a range of ways.” Why do you think that Westerners need to be reminded that Tibetans or Buddhists would express anger?

It’s interesting that they chose to do that. There was a Western woman who walked by the event and she said something to the Tibetans like, you shouldn’t be angry, this is bad karma. I thought, isn’t that rich? The irony, right? But Tibetans, they’re people. There’s a whole range of emotions that they feel. And, you know, I’ve seen the Dalai Lama be angry.

So, why do Westerners have this view of Tibetans? I think there’s just a romanticization of Tibetan Buddhism. It might be from pop culture and movies. People have remarked to me, when they hear about the book, they’ll say things like, ‘Oh, you should talk to these people who do podcasts about happiness,’ And to me, actually, that wouldn’t be what I would think of most immediately. One of the tenets of Buddhism is that life is suffering. That part doesn’t get as much attention in the West.

You described advances in women’s rights in the exiled Tibetan society that hadn’t happened within Tibet at the time. What did you see?

I happened to move into a Tibetan Buddhist nunnery in Dharamsala in 2008. I accidentally lived among nuns who were studying to be the first women to earn geshe degrees — the equivalent of a PhD in Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism, like many religions, is predominantly patriarchal. But the Dalai Lama was encouraging about the idea of female geshes, even though some in Tibetan society initially frowned on this big change. That was just one of the sea changes happening among Tibetan women in exile.

The Dalai Lama also encouraged women’s involvement in exile politics, activism, and society. The Tibetan exile parliament had a [minimum] quota for female officials: 6 out of 46 in 2009. That year there were 11 female parliamentarians.

You asked several of the exiled Tibetans in Dharamsala, India what actions led to them having to leave Tibet — and if they regretted coming to India. What did they tell you?

Well, it ranged. It varied. Just like it would because everyone is different. But there were three different responses that I’m thinking of. Topden, who came to India so he could freely study as a monk, said he didn’t really know the answer. A woman named Deckyi and her husband had to leave everything and flee in the winter of 2008 because they had photocopied flyers for a friend who participated in a protest and that friend was arrested. After that, they left everything, even though they had worked so hard to attain a middle-class life in Lhasa, Tibet. I said to her, “Do you regret making the photocopies?” And she said, “No, I don’t regret it. I did something good. We did something good for Tibet.”

And then I had asked the question of someone I interviewed briefly, a monk who had photocopies of the Tibetan flag. He was in prison for seven months for that. He was tortured. And he said he did regret it.

For most of the book, you were meeting with Tibetans in exile in India. Towards the end, you’re in Australia, where some of your contacts have moved. You document them celebrating Losar (Tibetan New Year) with full fanfare, which couldn’t be done inside of Tibet due to heightened Chinese security to thwart any unrest. Is there some sense that the future of Tibet it is now outside the country?

It depends who you ask — but from my perspective, Tibet within Tibet has to sustain itself however it can, and should sustain itself. And then outside of Tibet, it can flourish freely, and sometimes in a different way. So in India, through the Tibetan education system, there’s a very solid foundation to retain the language. When you go further away, like Australia, you’re not going to have a dedicated Tibetan education system in Australia, but I saw these weekend schools where children are learning the language and dance and arts and music on the weekends. They’re trying to keep it alive, and they’re doing that in other places where the diaspora has arrived. So, it sort of has to be both.

The year I was there in Dharmsala in 2009, they cancelled Losar, or they decided not to celebrate it, because of the conditions in Tibet. It is another form of protest, and it’s a political statement that’s significant. It would be like cancelling Christmas in the West. It’s really a big deal. And then, the first time I saw a Losar celebration was all the way in Melbourne.

Some people have said to me, “Oh, your book is about refugees. It must be depressing,” because that’s what they think of when they think of refugees. And actually, although there’s sadness, for sure, it’s also inspiring what Tibetans have done outside of Tibet, that I’ve seen. It’s probably inspiring inside of Tibet, too, but I can’t see that right now.

Danielle Preiss is a journalist who reports on global development, culture and the environment, with a focus on South Asia.

9(MDAyMjQ1NTA4MDEyMjU5MTk3OTdlZmMzMQ004))

© Copyright 2025 by NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.9(MDAyMjQ1NTA4MDEyMjU5MTk3OTdlZmMzMQ004))