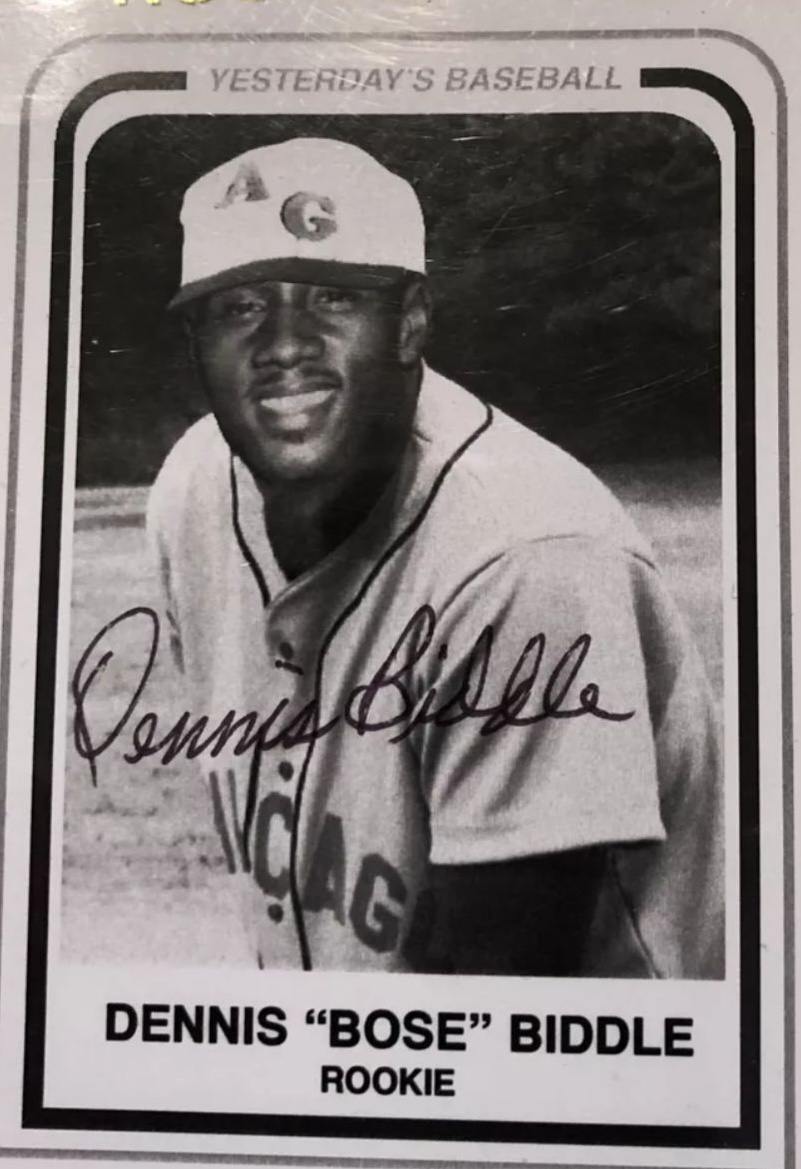

For decades, Dennis Biddle has been fighting to keep the memory of the Negro baseball leagues alive — and get pensions for the baseball players who played in the segregated leagues from the Jim Crow era.

This year, his goal was realized when Major League Baseball agreed to give pensions to former Negro league players who played for fewer than four years — and recognize statistics from those leagues in its record books.

Biddle, who is 89 years old, pitched for the Chicago American Giants in 1953 when he was 17 and 18.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“It was like family to me, the team,” Biddle recently told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “Those old men, they took me under their wing, took all of us young kids under their wings and taught us life skills, things that I needed to have to make it through this world and I’m appreciative of it today.”

The Chicago Cubs were interested in buying Biddle’s contract until an injury ended his baseball career. He then went to the University of Wisconsin and worked as a social worker in the Wisconsin correctional system and later in Milwaukee helping young people develop careers.

In 1996, Biddle founded Yesterday’s Negro Leauge Baseball Players Foundation to advocate for former players.

About 60 former players of the Negro leagues are still alive, Biddle said.

Baseball became popular among Black people in the 1800s, but they were unable to play in the professional leagues because of segregation.

Ken Bartelt, a doctoral student in history at UW-Milwaukee, wrote his master thesis on Black baseball teams in Milwaukee, called “Brew City Black Ball: Milwaukee as Microcosm of the Early-Twentieth Century Black Baseball Experience.”

After World War I, Black people began migrating to northern cities looking for jobs and fleeing the terrorism of the South, Bartelt said.

The first successful league was the Negro National League founded in 1920 by Rube Foster in Chicago. Bartelt told “Wisconsin Today” that the Black leagues were more than just recreation.

“You can’t really overstate how important they were to Black America during the Jim Crow period. It’s one of the first and most successful Black businesses on a nationwide scale,” Bartelt said.

Milwaukee had a couple of Black teams, including the McCoy-Nolan Giants, a traveling team, and the Milwaukee Bears, which both played in the 1920s. The Bears played only for the 1923 season, with a record of 14-52-1. Since the Black population of Milwaukee was relatively small, the team also struggled to attract fans, and moved to Toledo, Ohio. However, the team did host one of the first games officiated by Black umpires while it was in Milwaukee, Bartelt said.

Jackie Robinson became the first Black player in Major League Baseball in 1947, opening the door to thousands of other Black athletes. The Negro leagues continued for about a decade after that.

“Jackie had opened the door in ‘47 so that most of the Negro league teams became training ground for the major leagues,” Biddle said. “A lot of us came through that way — Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, Willie Mays, we all were prepared for the Major League by these Negro league teams that we were on.”

The Major Leagues exploited this system, both Biddle and Bartelt said, by buying out players’ contracts for little money.

“(The Black teams) were not being compensated enough for the talent of the players that they had, and it was really difficult for the Negro leagues to stay in business after integration, because a lot of Black fans, they started going and watching the Black stars play in the Major League games,” Bartelt said.

Bartelt said that there’s ample evidence that Black residents in Wisconsin took pride in the teams. When the McCoy-Nolan Giants played in cities around the state, they drew large crowds of Black residents.

“The legacy of the Negro leagues is the way that it was a Black-run institution that instilled pride in Black communities,” he said.

Biddle and other players will be honored in Milwaukee at the Milwaukee Brewers annual Negro League Tribute Game on Aug. 18 at 1 p.m. when the Brewers play the Cleveland Guardians. In conjunction with the game, Yesterday’s Negro League Baseball Player Foundation will hold several events in the city, including:

Friday, Aug. 16: Beckum Stapleton 95/60 GALA: 5-7 p.m. celebrating James Beckum, who played for the St. Louis Stars and founded Milwaukee’s Beckum Stapleton Little League in 1964, at Saint Kate Hotel, 139 E Kilbourn Ave.

Saturday, Aug. 17: Little Leagues All Star games: 10 a.m.- 2 p.m. at Beckum Stapleton Park, 911 N. Brown Street.

Sunday, Aug. 18: Holy Redeemer COGIC Wall of Fame Ceremony: 10-11:30 a.m. at 3500 W. Mother Daniels Way.