If you keep an eye out, you can see traces of something called the Red Arrow Division all over Wisconsin. There are parks and memorials named after it, and you even can see little red arrows on signs for Wisconsin Highway 32.

One of the most active and effective combat units in the Pacific Theater during World War II, the history and significance of the Red Arrow Division are not well known today — nor are its Wisconsin roots.

The 32nd “Red Arrow” Infantry Division was the first U.S. Army division to take the offensive against the Japanese military and the first to defeat them in battle. In total they racked up 654 days of fighting — more than any other U.S. Army division during World War II.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The division was formed around National Guard units from Wisconsin and Michigan.

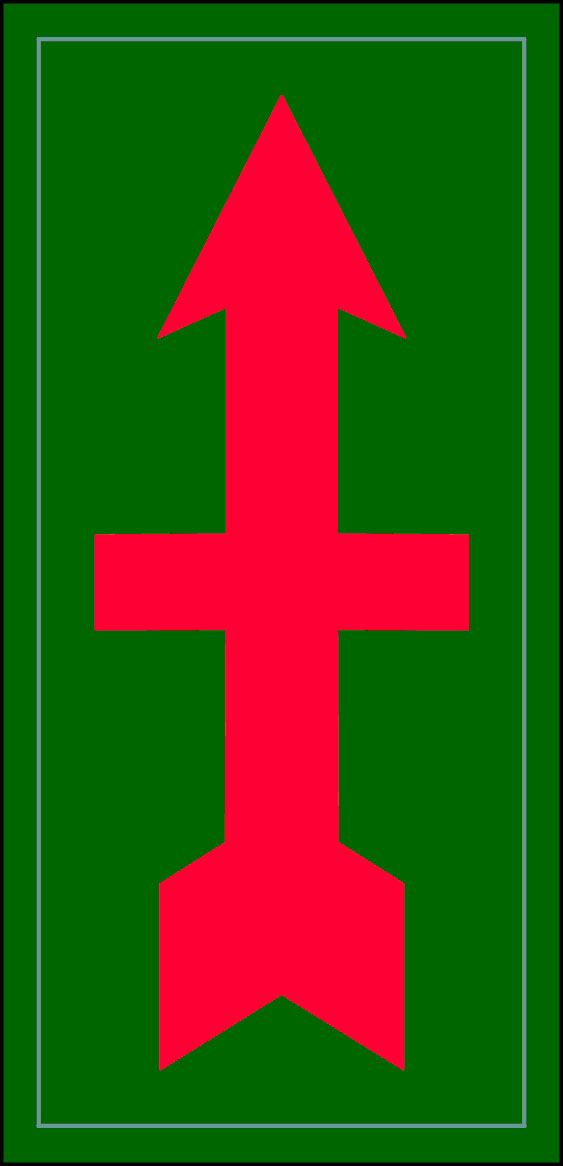

32nd Infantry Division shoulder sleeve insignia. U.S. Military (cc)

Sign for Wisconsin Highway 32, featuring the Red Arrow insignia. SPUI (cc)

Manitowoc-born author Mark D. Van Ells told the division’s story from the perspective of the soldiers in his recent book, “Red Arrow across the Pacific: The Thirty-Second Infantry Division during World War II.” A professor of history at Queensborough Community College of the City University of New York, he joined WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” to share what he learned about the Red Arrow Division.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Rob Ferrett: What made you want to tell the story of the Red Arrow Division?

Mark Van Ells: I grew up in Wisconsin, and the 32nd Division was made up of National Guard soldiers from Wisconsin and Michigan, so there’s a local connection.

As I started to study history professionally, I noticed that not much had been written about the Red Arrow Division. It seemed to be everywhere in the Pacific: It was the first U.S. Army Division to go into battle against the Japanese, it ended the war on occupation duty in Japan, and it wasn’t demobilized until 1946.

And yet there really wasn’t that much written about the division. It seemed like there was a missing story there.

RF: How was the Red Arrow Division formed, and how did it get its name?

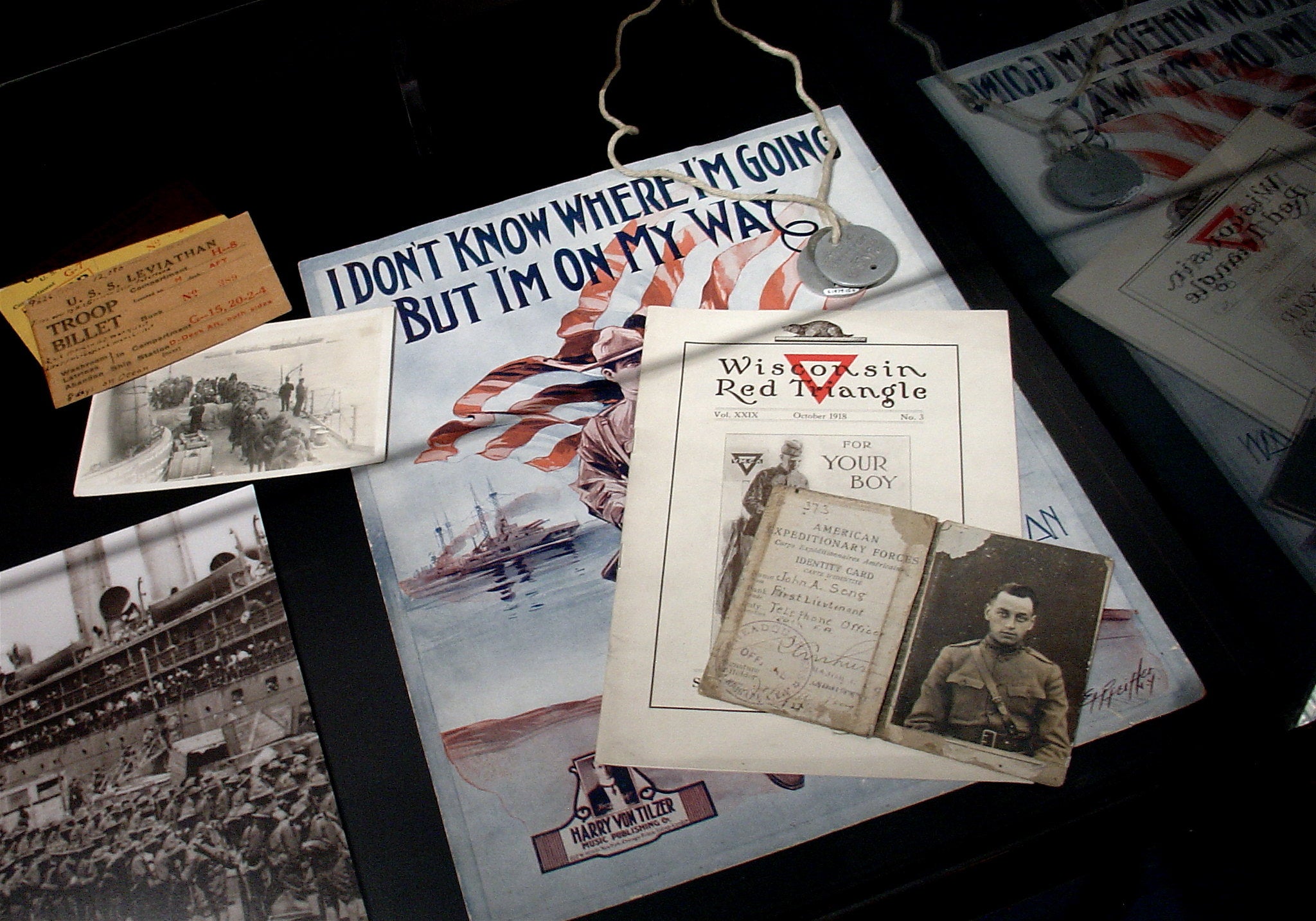

MVE: It was formed during the First World War. … It trained at Camp MacArthur in Texas and then shipped off to France and participated in some of the most important battles in the First World War. It gained a reputation as one of the United States’ most effective combat divisions during the war, including the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

They punctured every German line during the First World War. That’s where the Red Arrow symbol came from. You see that red arrow pointing upward, and the horizontal bar across the middle of it. That was meant to symbolize that they crossed over every German line.

RF: What kind of position was the Red Arrow Division put in when they were deployed to Papua New Guinea in the Second World War?

MVE: I think it’s fair to say it was an impossible position. They did not have the training. They did not yet have the equipment. I think it’s also fair to say that those at the top of the chain of command did not understand what they were getting into.

Very few Americans had ever been to New Guinea. They didn’t really understand the jungle environment and American troops — the Red Arrow more than most perhaps — went into battle very, very confident.

They also had some faulty intelligence and didn’t quite understand just how many Japanese troops they were facing. … They ultimately did prevail, but those first few days on the battlefield these soldiers had to learn some really tough lessons about what combat is actually like. It wasn’t like the movies, it wasn’t like a training exercise. This was real, and a slip up meant death or injury.

RF: To what extent was disease and nature a formidable enemy for the soldiers in Papua New Guinea?

MVE: Malaria was a massive problem with the 32nd Division, and being the first U.S. Army infantry division to go in, they suffered perhaps more from malaria than any other division in the entire U.S. Army.

The preventive measures hadn’t been developed yet and the drugs to treat malaria were inadequate. They were camped outside in these jungles, going through the mountains, constantly being bitten by mosquitos. Most members of the division ended up suffering from malaria by the time the battle of Buna-Gona was over.

RF: What kind of weapons and support did the Red Arrow Division have in New Guinea?

MVE: There were no tanks until late in the battle. It was very difficult. New Guinea is a place with very dense jungles, no real road network, no port system. Transporting heavy equipment like that was a very difficult thing to do. They did not have much artillery support.

In this case, leaders at the top of the chain of command believed that they could use airplanes to provide the artillery support, and that turned out to be not adequate enough.

The Japanese, meanwhile, had built these very well-camouflaged fortifications and entrenchment systems, in some cases reinforced by cement and steel doors. Going through these swamps, there were only certain pathways you could take, and the Japanese concentrated their defenses there.

With the weapons that they had — the mortars, the grenades, the rifles — they were not able to punch through most of these defenses. Not until the tanks came in were they really able to make substantial headway at Buna.

RF: What kept the soldiers going during these challenging battles?

MVE: Studies of soldiers in war oftentimes suggest that soldiers fight for each other more than anything else. If you let your comrades down in battle, others might be killed, and that’s a great motivating factor for you to keep fighting and do extraordinary, heroic things.

I don’t think we can dismiss the idea of patriotism and love of country either. Remember, the United States entered World War II with the attack on Pearl Harbor. Those feelings were very, very high.