Food doesn’t last long in Leisa Winston’s home, where she takes care of nine grandchildren.

“Every day after school, it’s somebody (saying), ‘Granny, I’m hungry. Granny, you got something sweet?’” Winston said.

The Milwaukee retiree relies on food assistance to stock her kitchen with some of her grandkids’ favorites.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But feeding everyone got tougher in January when a winter storm swept across Wisconsin. It knocked out her power for roughly 24 hours, leaving about $200 worth of food and milk in her fridge and freezer to spoil.

The family survived the next two weeks on peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, hot dogs and bologna, Winston said. She told the kids: “It might not be a steak dinner, but your little tummies are full.”

She couldn’t afford fresh milk or meat until she got additional funds through FoodShare, Wisconsin’s food aid program for low-income people.

The federal government funds FoodShare through its Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP. It allows states to replace funds for households that lose food to misfortunes like refrigerator malfunctions, power outages or flooding.

But many aid recipients don’t know that’s an option, local food assistance experts say.

Those who are aware face what advocates call unnecessary hurdles. They include requirements in Wisconsin and most states that recipients hand-sign a verification of loss form. That means people like Winston who lack access to a home printer must pay for transportation to an office that has one.

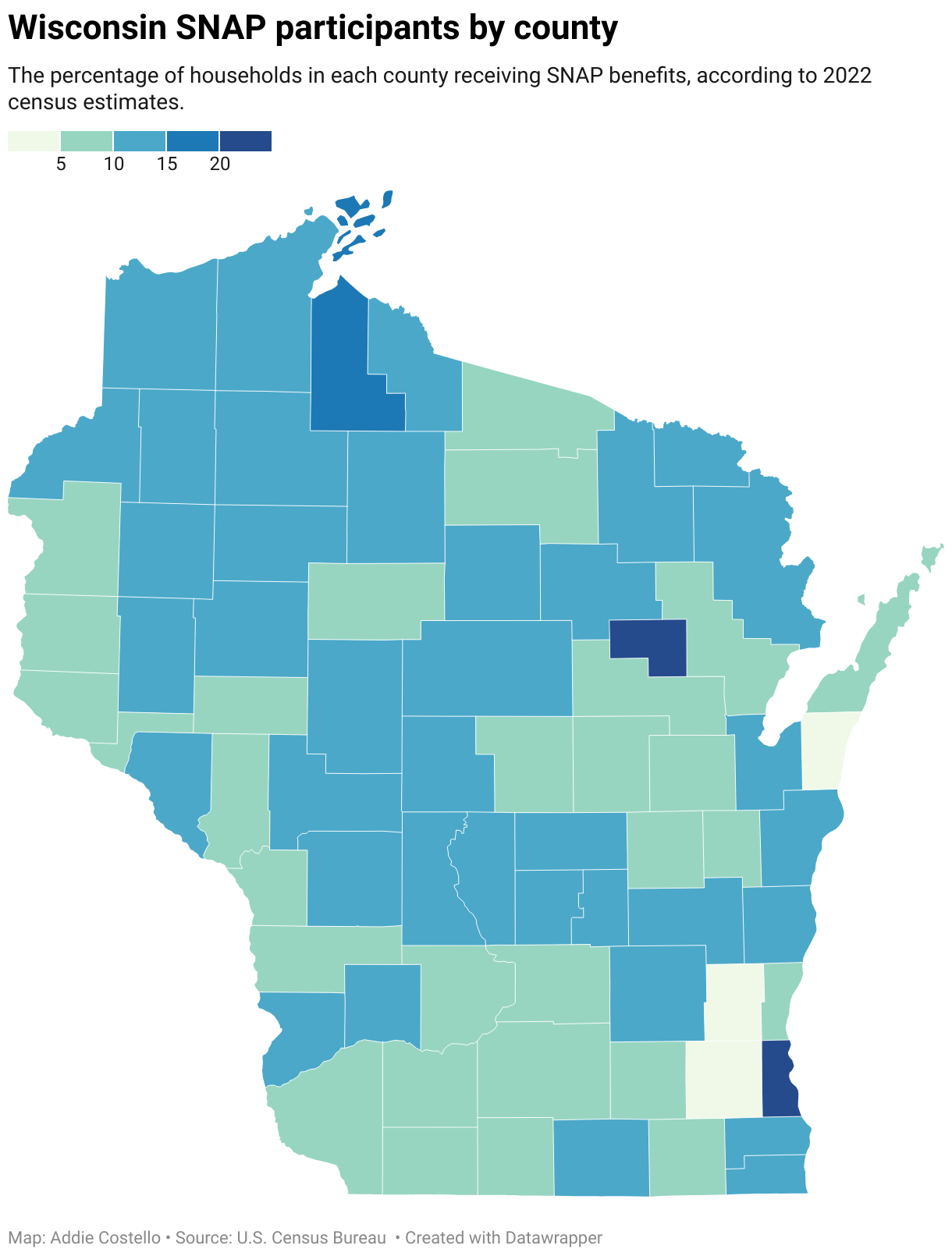

That may help explain why only 6 percent of the estimated 127,500 SNAP households the state health department identified as potentially affected by Wisconsin’s January outages applied for replacement benefits, according to state data obtained by WPR and Wisconsin Watch.

Nearly 26,000 FoodShare households in Wisconsin received $3.1 million in replacement benefits between December 2022 and November 2023. That’s far less than the up to $34 million in food that FoodShare households potentially lost from January’s storm alone, according to a state estimate.

Such barriers may grow more consequential as climate change drives more extreme weather in Wisconsin and other states. The number of weather-related power outages nationwide increased by more than 75 percent during 2011-2021 compared to the previous decade.

Wisconsin is gradually moving to simplify FoodShare replacement requests. It plans to join at least nine other states in allowing applicants to electronically sign replacement aid forms.

But although Oklahoma updated its process in a matter of days, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, which rolled out digital signature options for other forms a decade ago, doesn’t plan to accept online signatures for FoodShare replacement until October — after the state’s typical tornado season.

The delay means FoodShare recipients may still face reimbursement challenges this summer if severe storms knock out power.

Over the past decade, six of Wisconsin’s seven federally declared natural disasters happened between June and September.

Challenging process for requesting FoodShare replacement funds

Winston had used FoodShare for less than a year before the January storm. She didn’t learn about replacement benefits until her friend saw a news report about how Hunger Task Force was helping affected residents.

Upon calling the anti-hunger nonprofit, Winston learned she could request funds to buy fresh milk and meat before her usual monthly benefits were set to reload — a “blessing,” she said.

“I never knew all these resources are here to help people. There’s really, really a need,” Winston said.

Determined to keep her family fed, she said she spent her last two dollars taking the bus to a Hunger Task Force office to sign the form by hand.

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services, at the time, temporarily accepted signatures over the phone, but outside groups like Hunger Task Force are not authorized to accept phone signatures.

FoodShare recipients who call the state health department after major outages often experience long hold times, a Hunger Task Force spokesperson said. Residents typically have little time to waste in seeking to replenish their food supplies. The window to request replacement funds is 10 days after the event that triggered the misfortune, unless the state requests an extension from the federal government.

That’s what happened in January, giving Wisconsin residents about a month to document their food loss after the storm.

Winston filed her replacement benefit form as soon as she could, and she waited about two weeks for replacement benefits to show up on the QUEST card, which she uses to purchase food.

Feeding America, a national food bank network with multiple Wisconsin offices, recommends printing, signing and then uploading the form as the fastest way to get benefits under the current system.

How other states handle SNAP replacement requests

Had Winston lived in one of at least nine other states, she could have completed a simple online form without worrying about phone hold times or bus fares, according to a WPR and Wisconsin Watch analysis of the request process in 50 states. Seven additional states regularly accept someone’s voice over the phone as a signature.

In most cases, Wisconsin offers neither.

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services says states need federal approval to change signature requirements.

The United States Department of Agriculture oversees SNAP. In 2016, it sent a memo to regional SNAP directors to clarify that, for initial applications and recertifications, “any electronic means of conducting the SNAP certification process may be suitable for electronic signatures,” including over the telephone. It said “state agencies may not fully realize the methods available” to improve efficiency.

That memo, however, did not give guidance on replacement benefit forms.

A spokesperson for the Midwest Regional Office of the USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service said states still need a federal waiver to roll out digital signatures on replacement benefit forms.

But Oklahoma and Tennessee’s SNAP agencies told Wisconsin Watch and WPR they did not need federal permission to make their changes.

Following a major ice storm in October 2020, Oklahoma Human Services added online signature options for replacement benefits within 10 days — allowing applicants to submit required forms over their phones, a spokesperson said.

SNAP agencies in California, Florida, Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota and Tennessee also confirmed they accept electronic signatures for reimbursement forms.

Wisconsin plans to remove signature barriers for FoodShare replacement requests

Wisconsin’s health department applied last September for a waiver, which USDA approved two months later.

“The current method of electronically signing for applications and renewals has been effectively used by all agencies in Wisconsin for over 10 years,” the agency wrote in its request. “All workers are thoroughly familiar with and comfortable using this method of collecting signatures.”

That includes within the initial FoodShare application process, where applicants can submit digital signatures to the state’s website or app or sign over the phone. The health department will use similar digital signature options for the replacement benefit form.

Despite having expanded signature options for other forms, the state’s target date for implementing new digital signature options for replacement forms isn’t until October 2024.

“DHS understands that providing telephonic or electronic signatures is more convenient for members, which is why we continue to pursue these options while making sure that we meet federal requirements,” spokesperson Jennifer Miller told WPR and Wisconsin Watch in an email. “Doing this requires changes to documents, systems, and processes.”

The delay gives the health department and local SNAP agencies time to transition without disrupting recipients’ benefits, Miller added.

Little awareness about food aid replacement

Even with a more accessible process, many Wisconsin residents won’t know they can ask for replacement aid.

SNAP agencies nationwide struggle to draw attention to the option, Cundari said.

While local SNAP offices have information about replacement benefits on posters or pamphlets, clients are less likely to visit offices today, Cundari said.

The information gap affects more than just replacement benefits. Local agencies often struggle to get the word out about other SNAP program forms and requirements, Cundari said, adding that she’s seen few solutions to the problem.

After major outages, Wisconsin’s health department emails community partners about the reimbursements and posts information on its updates page, Miller said.

The reimbursement form asks recipients how and when their food was destroyed and how much it was worth. It asks for proof of the loss, such as a letter from a utility confirming the outage.

But the state already has enough information about each FoodShare household to know who likely needs assistance after major outages, Hunger Task Force CEO Sherrie Tussler said.

“They should just use (their databases) to approve and support people who are in trouble rather than putting them through some kind of unnatural gauntlet of paperwork,” Tussler added.

States can get USDA approval to automatically reimburse recipients in some situations. It requires proof that more than 50 percent of a defined area, like a county, city or zip code, lost power for at least four hours.

Normally, states issue automatic replacements only during declared disasters, but that isn’t a requirement.

At least 19 states have issued mass replacement benefits 47 times in the last five years, a WPR and Wisconsin Watch analysis found.

Wisconsin hasn’t issued mass replacement benefits in at least 15 years, but only one disaster during that period potentially caused food loss, Miller said: a January 2020 storm that ravaged lakeshore communities in Kenosha, Racine and Milwaukee counties.

But the state has issued Disaster SNAP benefits to help those affected by significant events, Miller said. Under Disaster SNAP, FoodShare recipients can receive supplemental benefits.

Climate change adds urgency

Midwest SNAP agencies have not traditionally focused much on disaster preparation compared to agencies in more disaster-prone states, particularly in the South, Cundari said.

Southern states “just have this philosophy of very much like not if we have a disaster, but when, and our Midwest states are not there yet,” Cundari said.

That has begun to change in the aftermath of the derecho that walloped much of the Midwest in 2020. Food aid officials know severe weather is becoming more frequent in the region, and they are strategizing ahead of future disasters. Learning from policies in southern states can help, Cundari added.

“With climate change, these storms are becoming as detrimental to households as the hurricanes that you’ll see in Florida.”

This story comes from a partnership of Wisconsin Watch and WPR. Addie Costello is WPR’s Mike Simonson Memorial Investigative Reporting Fellow embedded in the newsroom of Wisconsin Watch.