The Common Loon is Wisconsin’s symbol of wilderness and early summer.

But there’s been a 22 percent decline in the state’s loon population over the past three decades. According to research published in the journal Ecology, that decline is due to climate change and poor water clarity.

Walter Piper, lead author of the report and also director of the Loon Project, says loon chicks are entirely dependent on their parents for food.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“They’re visual predators so they chase their prey, mostly fish underwater. If there’s a sudden change or decrease in the clarity of the water, that seems to make it much more difficult for them to find prey and the chicks end up suffering,” Piper said on WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

Teams from the Loon Project have been studying loons in Wisconsin’s northern lakes since 1993 and have since noticed the steep decline.

The next research step is to determine the cause of poor water clarity, which could be sediment or fertilizer from lawns. Piper hopes fertilizer is the main culprit, since there’s an easy solution: Have property owners stop using it.

“I’ve studied loons for 32 years and I don’t want my legacy to be the disappearance of my study animal,” he said.

Piper discussed his research with “Wisconsin Today.”

The following was edited for brevity and clarity.

Kate Archer Kent: Your report is trying to determine what is contributing to the decline in the loon population. What are you finding in northern Wisconsin?

Walter Piper: There has been a decline over the last quarter century in the masses or weights of chicks and there’s also higher mortality among chicks. So the question is what could be causing that? Since their masses are lower an obvious suspect is food.

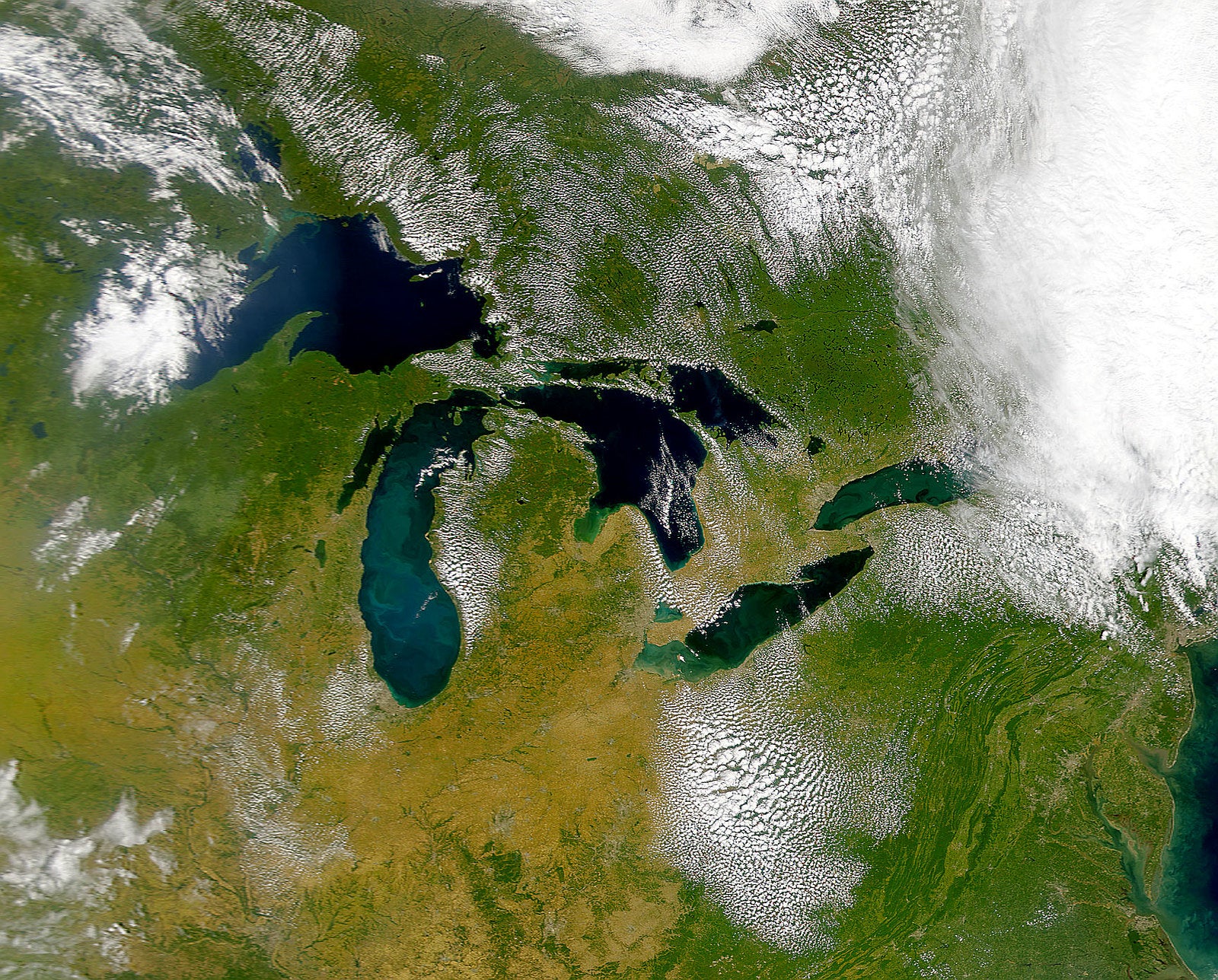

So we got together with a couple of collaborators at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (in New York) who use satellite data to measure water clarity. They can go back 40 years in time, and we could pull together their satellite data measuring the water clarity in our lakes, together with the chick mass data. And what we found was that there was a very close correlation between the masses of the chicks and the water clarity that the satellite data was showing.

KAK: That’s interesting. So in murky water, those loons have a difficult time diving and seeing their prey?

WP: That’s what we presume, yes. … They simply can’t find enough food to feed their chicks as much as they would like to. Of course, they have to feed themselves, they have to keep themselves alive. They’re long-lived animals and have to take an eye to the future and keep themselves alive for 20, sometimes 30 or more years.

KAK: We also have the difficulties with the algae blooms, the invasives on lakes. Is that an issue for loons?

WP: Well, the second stage of this work is to (discover) what might be causing that decline in water clarity. It could be something as simple as sediment washing into the lakes. … It could be fertilizer, as you suggest with the algal blooms. It could be that nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers that people are putting out on their lakeside lawns are causing a bloom of phytoplankton, which make the water less clear and therefore makes a loon struggle to feed their chicks. We’re not sure.

KAK: Why is July a sensitive month for the loon population?

WP: Loons are sitting on nests now and the chicks are just about to hatch. The chicks typically hatch in June sometime, so June is an important month, too. But July is the most critical month for most loon pairs because their chicks are rapidly growing. And therefore the chicks are very demanding of food and are growing at a rapid rate if the parents can provide enough food to allow that to happen. So it’s just a critical month for chick growth and survival.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.