If you have an old tree on your property, its branches likely hosted passenger pigeons long ago.

The species has been extinct for over a century now, but researchers are testing trees in Wisconsin to look for signs of the passenger pigeon’s role in the ecosystem. The plan is to bring the bird back and slowly reintroduce it to the forests they once roamed.

Scientist Ben Novak is leading the research for the nonprofit Revive and Restore, which focuses on biotechnology in conservation. He’s partnering with Steve Apfelbaum from the Applied Ecological Institute in Wisconsin to test local trees to see how well they would respond to the reintroduction of the species.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Then, Novak and his team would use DNA editing to breed new passenger pigeons from existing pigeon species, with the hopes of building back the population that was hunted to extinction in the early 1900s.

Novak joined WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” to discuss the project and Wisconsin’s history of the passenger pigeon.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Rob Ferrett: Tells us the story of the passenger pigeon. What was its role in Wisconsin and how did it go extinct?

Ben Novak: Back in 1955, a man named A.W. Schorger basically wrote the book on the history of the passenger pigeon, and he was from Wisconsin. He used a lot of historic records from Wisconsin to piece together what we know about passenger pigeons.

Basically, what made that species so famous was in the early 1800s, before they went extinct in 1914, they were the most abundant bird in North America — likely the most abundant bird on the planet.

And because they were so abundant, just like the American bison, they were easy to go out and kill and trap a whole lot at once. So, they were fed upon by people in the millions.

Industrial-scale hunting went out to get them for commercial food markets, and in a matter of just a couple decades, they went from 5 billion birds to just a few thousand birds flying about. The very last birds were killed in the wild in 1902 around Indiana and Illinois. And then there were just a few of them living in a zoo at Cincinnati, and they slowly died off.

RF: What is it about the passenger pigeon’s role in the ecosystem that has you and your colleagues wanting to bring them back?

BN: These flocks of a billion birds would cause mayhem in the forest. And while that sounds counterintuitive, what we know in forestry science today is that beautiful, big oak trees and a host of different species that we think of as so iconic, they’re dependent on things like forest fires and storms.

These disturbance events come in and cause damage in the forest so that sunlight can get down to the forest floor and allow new growth to start over. They rely on what we call the forest cycle to go over and over again from disturbance and regeneration and succession.

For decades, people thought the primary driver of these disturbance events that are so vital to the biodiversity of forests were mainly from storms and fires, but people had kind of forgotten about the passenger pigeon. These flocks of billions of birds would come into the forest, overcrowd on branches, break branches and entire trees down from their weight.

Then, as they ate the food over a few days, they built up a whole lot of guano, several inches deep on the forest floor like a blanket, and that snuffed out everything much like a fire would clear out the vegetation of a forest floor. But unlike a fire or a storm, this is more like a tornado dropping fertilizer on the forest.

All we have are these anecdotes that wherever these passenger pigeons roosted or nested for a few weeks at a time would be the greenest patch of forest or the most rich future farmland. That’s our basic value proposition for the idea of bringing these birds back into the ecosystem.

RF: What kind of passenger pigeon research are you working on in Wisconsin?

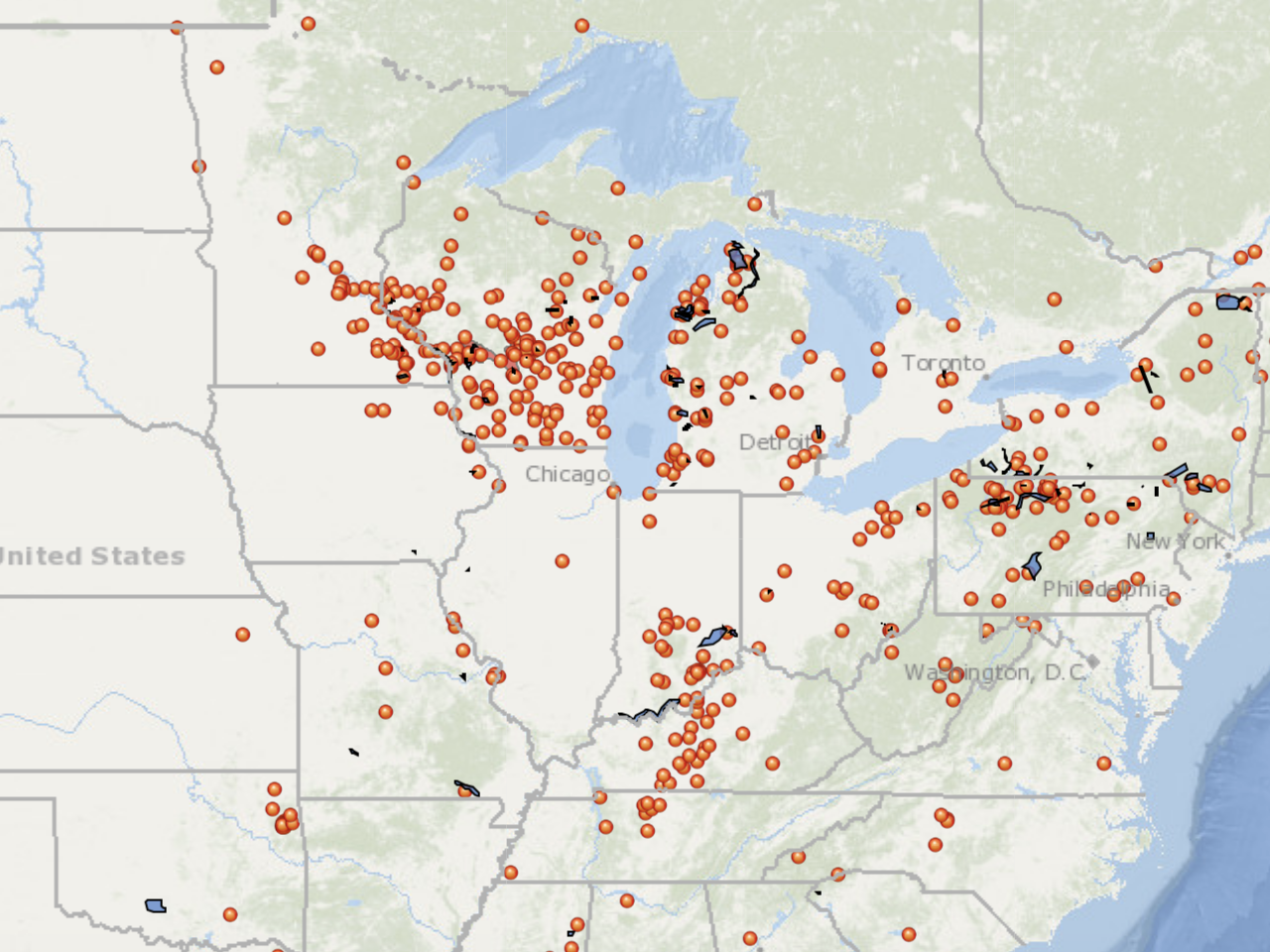

BN: Wisconsin was home to the largest nesting record in history. We’re hoping to engage with local landowners whose land may have actually once been host to a nesting site of passenger pigeons.

If anyone in Wisconsin has a tree in their yard that is over 150 years old, I guarantee that tree had passenger pigeons on its branches at one point in time, and that’s a direct connection to that past. We want to start using that connection to learn more and possibly create an experiment where we could actually figure out if what we hypothesize about this important role in the forest is correct and accurate, and how significant it actually will be to the future of forests.

RF: How would you actually bring the extinct species back to existence?

BN: The idea is that we can sequence their DNA from the specimens you find in museums. If we can figure out the differences in their DNA that are responsible for their unique traits — the things that made passenger pigeons flock in these dense, large flocks, that created these forest disturbances — then we can then use modern gene editing technology and take a living relative and change its DNA to start to match that of the extinct passenger pigeon.

RF: How long do you think it would take to bring passenger pigeons back this way?

BN: We believe we can probably start recreating the bird between 2029 and 2032. So hopefully, in the 2030s we have a flock of birds living in an aviary that is starting to look and behave like historic passenger pigeons. That’s where the real conservation work begins, similar to how peregrine falcons were restored to the eastern forests or whooping cranes in the central U.S. People have to breed those birds, and these aviaries condition them to get back out into the wild and then produce enough of them to form sustaining flocks in the wild. And that can take decades.

Editor’s Note: If you want to learn more about the project or have your trees tested, you can contact lead scientist Ben Novak at ben@reviverestore.org