From the care of Wisconsin researchers to the International Space Station, a group of tomato plants rode on a rocket last week with the goal of brightening astronauts’ days — and their diets.

But first the tomatoes are trying to find their own joy.

Growing without gravity is stressful to tomatoes, said Simon Gilroy, a University of Wisconsin-Madison botanist who runs a lab that studies plant development.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“When you move into space, it will cope, but it is clearly not happy,” Gilroy said. “We see that the plants grow a little bit slower, and they switch on a lot of their defenses.”

Scientists hope to help the tomatoes find happiness without gravity by setting the plants up with a fungus from the genus Trichoderma. Like a romantic comedy, they expect the tomatoes to first put up walls and repel the fungus as a bad match. But after a few days, the pair will come together in a symbiotic relationship as the fungus ameliorates plant stress.

“Biology is absolutely, mind-blowingly amazing,” Gilroy said recently during an appearance on WPR’s “Central Time.”

The tomato plants launched into space as part of NASA’s Cygnus mission, which left the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida on Jan. 30. The mission successfully docked at the International Space Station two days later.

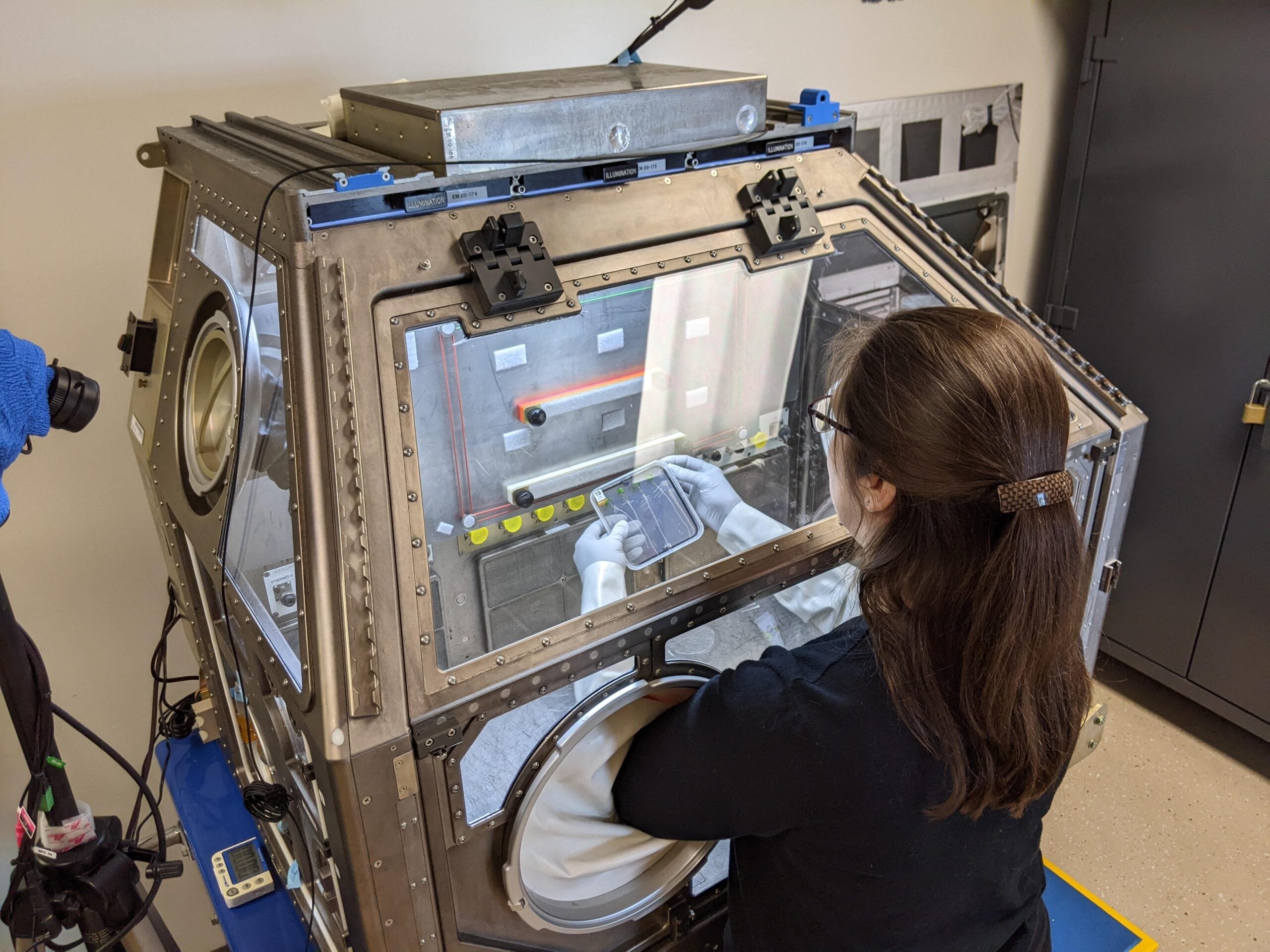

The tomatoes experiment, known as TASTIE, is being overseen by UW-Madison and University of New Mexico researchers. The project name is short for Trichoderma Associated Space Tomato Inoculation Experiment.

On “Central Time,” Gilroy discussed seeing the spacecraft take off, how plants can grow without gravity and why scientists picked tomatoes rather than other plants for this experiment.

The following was edited for brevity and clarity.

Shereen Siewert: What did it feel like watching your work shoot up into space?

Simon Gilroy: We’ve seen multiple launches, and every time it’s absolutely amazing. Just watching a rocket launch is amazing, but watching a rocket launch that has your stuff on top of it — it’s very difficult to describe to people who haven’t seen it.

SS: It never occurred to me that gravity could be a key player in why plants grow the way they do. Can you explain why?

SG: Gravity is the great constant. It’s everywhere. It has been unchanging for the whole history of life on Earth. … It affects so many things, things that you don’t even necessarily think about. You can definitely go, “Oh, well, we know up from down as human beings, and we can sense that direction.” Plants can clearly do that, as well.

Roots growing down, shoots growing up — that’s sensing gravity. It affects how water moves. It even affects how the air and gases around plants move. All of those things together shape how biology operates.

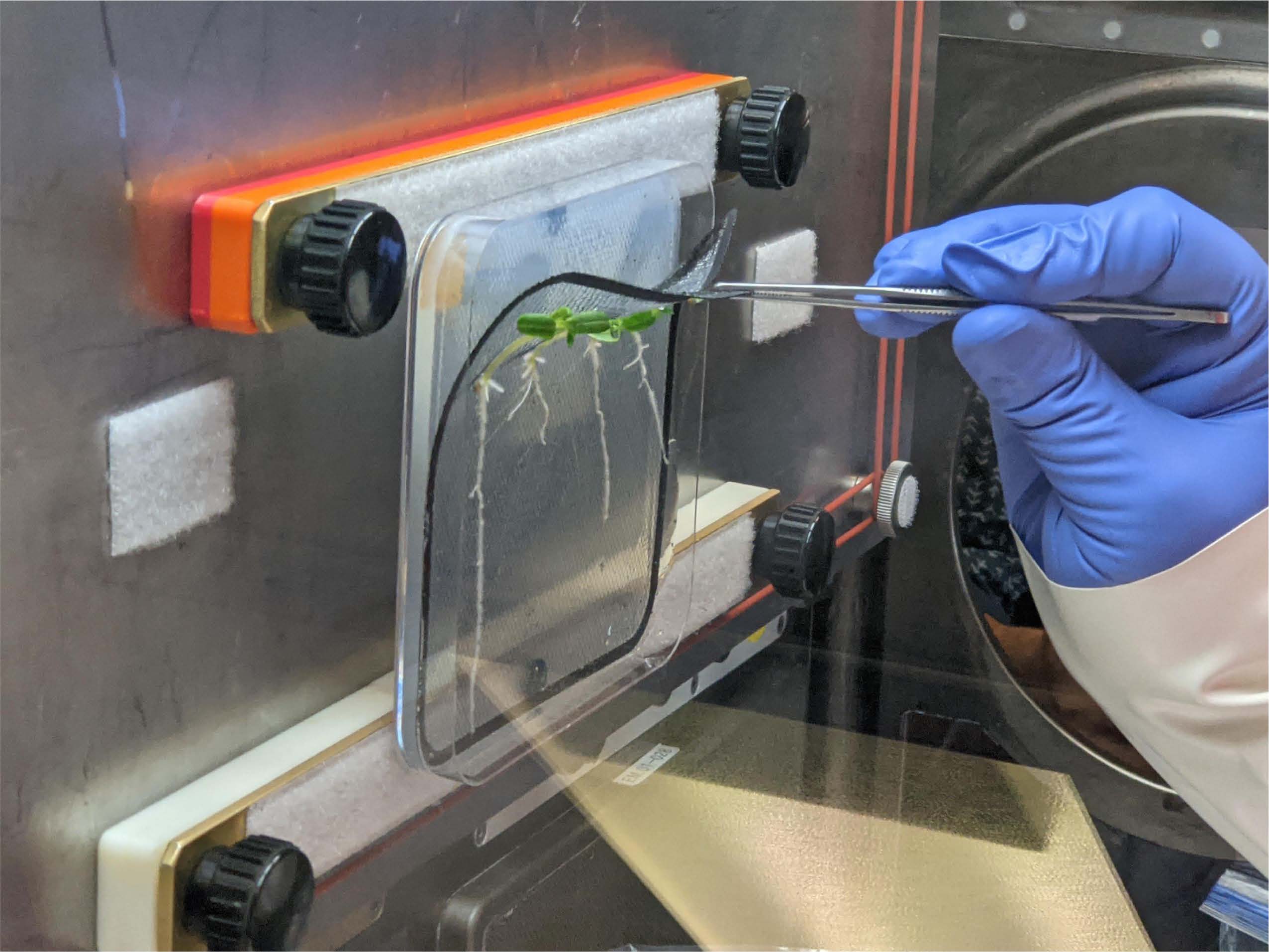

SS: How do you try to account for the lack of gravity and get the plant to grow in the right direction?

SG: Plants cope. Astronauts cope with being in space, and plants cope with being in space. It’s that whole thing, “Life will find a way.” Plants have to grow in a direction. So, the roots are going to have to grow in one direction. The shoots are going to grow in another direction.

They key into something else. Plants are fantastically sensitive to their environment. We provide them with lights. The gravity cue, which is that basic background cue, disappears. But light is a very, very powerful cue for plants. So, the shoots grow towards the light and the roots grow away from the light.

SS: What do you expect the fungus to do in this experiment?

SG: Biology very rarely works alone. Plants don’t work on their own just growing in the natural world. There’s a lot of symbiotic interactions that occur. There’s a naturally occurring fungus in the soil … and it’s everywhere. It’s on your feet at this moment. It’s a naturally occurring fungus, and it interacts with plant roots.

When it first interacts with the plant, the plant just freaks out. It sees a fungus, and it thinks, “Bad pathogen.” It switches on defenses and all the things you would imagine it would do to defend itself. But then over the course of a couple of days, they come to an agreement. It turns into a symbiosis where both plant and fungus benefit.

SS: Why tomatoes? Why not other fruits or vegetables?

SG: There’s a lot of background that goes into an experiment in space, and there has been a lot of plant biology that has been done on the space station. We have flown a lot of different plants. … We want to understand what happens to plants that potentially could be part of an astronaut diet. Maybe not sustaining the astronaut with everything they eat, but you have no idea how grateful they are when they get fresh fruit and vegetables that go up there.

A lot of what is grown in space are leafy greens, because one of the things you want to do is eat most of what you’ve grown. Things like lettuce, cabbage — you do consume most of the plant. But who wants to live with lettuces and cabbages for their entire life?

It turns out that tomatoes have lots of bonuses. They provide some variety. The tomato fruit has a lot of beneficial chemicals in it. For the astronauts, one of the things we want to give them is a lot of antioxidants. Tomato fruits are a fantastic way to do that.

SS: What would success look for you in this experiment?

SG: We’re hoping that the tomato plants that are inoculated with this fungus grow into huge, bushy, healthy plants. If we saw that, we would be pretty happy.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.