In Western Wisconsin, about an hour from the Twin Cities, there’s a road that splits to the north. As I drive down it and approach my destination, I see a sign: “Welcome to Sandland. Take only pictures, leave only footprints.”

The complex is the creation of Eric Sutterlin, a contract mechanical engineer who lives outside Minneapolis. Sutterlin bought the plot of land in Wisconsin that became Sandland in 2011. Over the years, he’s built a network of volunteers who help out when and how they can.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

From the entrance of Sandland, several of its attractions are visible. Up the hill on the right is a decommissioned monorail from the Minnesota Zoo in the Twin Cities. Volunteers made the driver’s cabin into a miniature museum. To the left, there’s a treehouse one of Eric’s collaborators built a few years back but had to bring to ground-level due to safety reasons.

But the main attraction is down the hill, straight ahead: the tunnels.

Eric says there are a few ways to enter the tunnels. There is a door marked as an exit and then what he calls the “intended visitor experience.” I choose the latter. We put on knee pads and headlamps. Eric turns the generator on, to provide power to collaborator Dave Gerboth for tunnel chiseling later in the day.

The intended entrance to Sandland is only about three feet tall. The only way through here is to crawl. The only light in the tunnels comes from our headlamps.

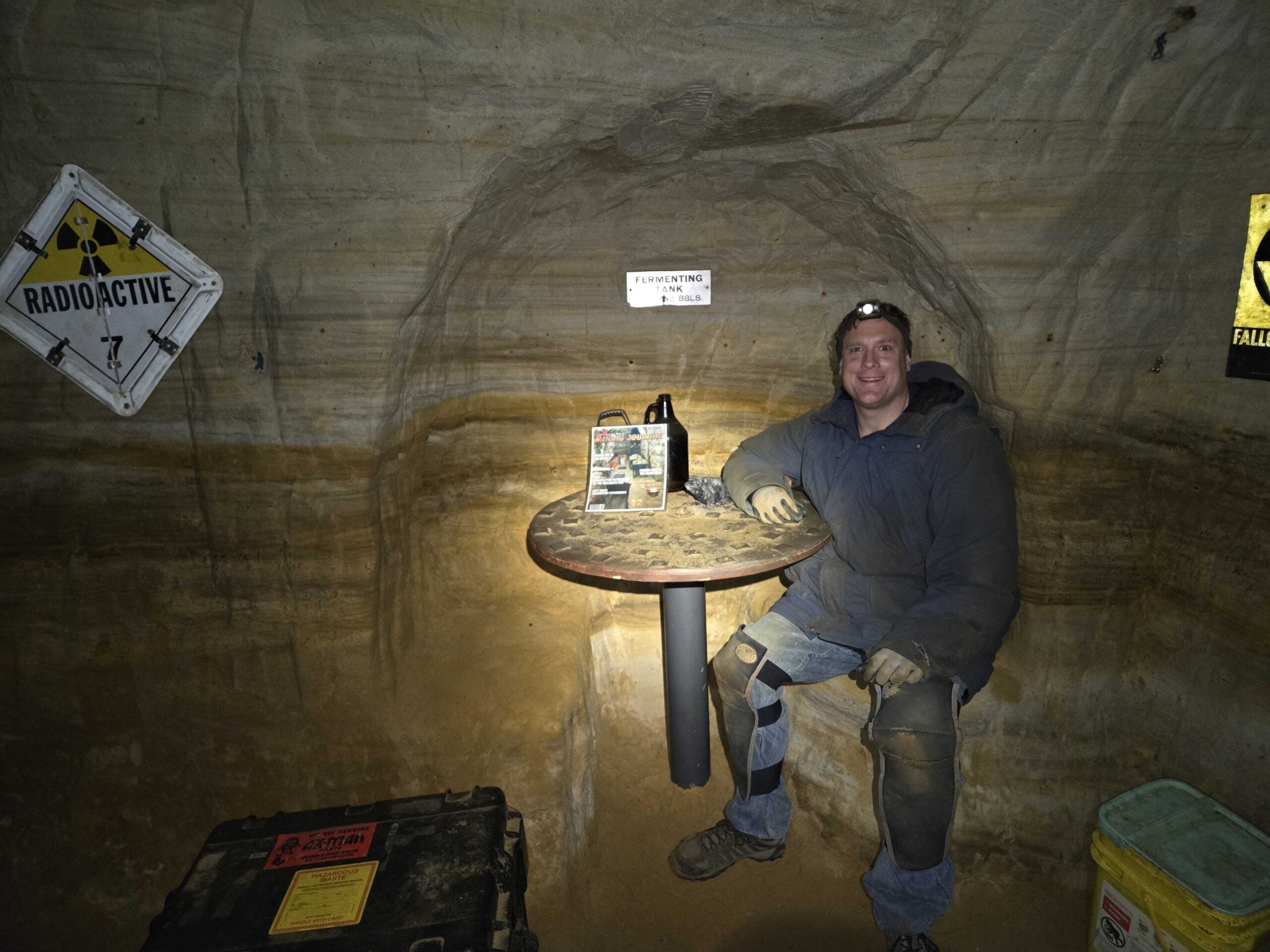

This tunnel system is made of Jordan sandstone, native to Wisconsin and other states in the upper Midwest. In the tunnels, it looks like horizontal layers of white, orange and grey stone that speckles a bit under direct light.

You may wonder about the safety of going through the tunnels at Sandland. It’s certainly something I considered while on my hands and knees, crawling through a hole into the side of a cliff face.

“I feel pretty confident that the risk of exploring our tunnels is very low compared to a lot of you know, common activities like riding a bicycle,” Sutterlin said. “And I think for people who are mobile and outdoorsy, I think their reward is very, very much worth the risk.”

After crawling for about 70 feet, I reach a fork in the road. One tunnel goes left, one to the right. The entrance to Sandland isn’t just a crawling tunnel — it’s a crawling maze.

“I deliberately designed the maze so that you can’t see any other intersection from any given intersection, because that makes it more confusing and mysterious,” Sutterlin explained. “The mystery, the question mark, what’s down that tunnel? That’s what a lot of us love.”

After nearly an hour of exploring the maze, Sutterlin guides us to a large, circular area that he dubs the “donut room.”

The donut room is essentially a hub area that connects the rest of Sandland together. Each side tunnel here curves too, leaving you with no idea what’s around the corner. Some are deliberate dead ends; others lead to attractions still under construction, like an underground slide and a standing-level labyrinth called the Globe Maze.

But the end-goal of Sandland was created by a volunteer named Gabe.

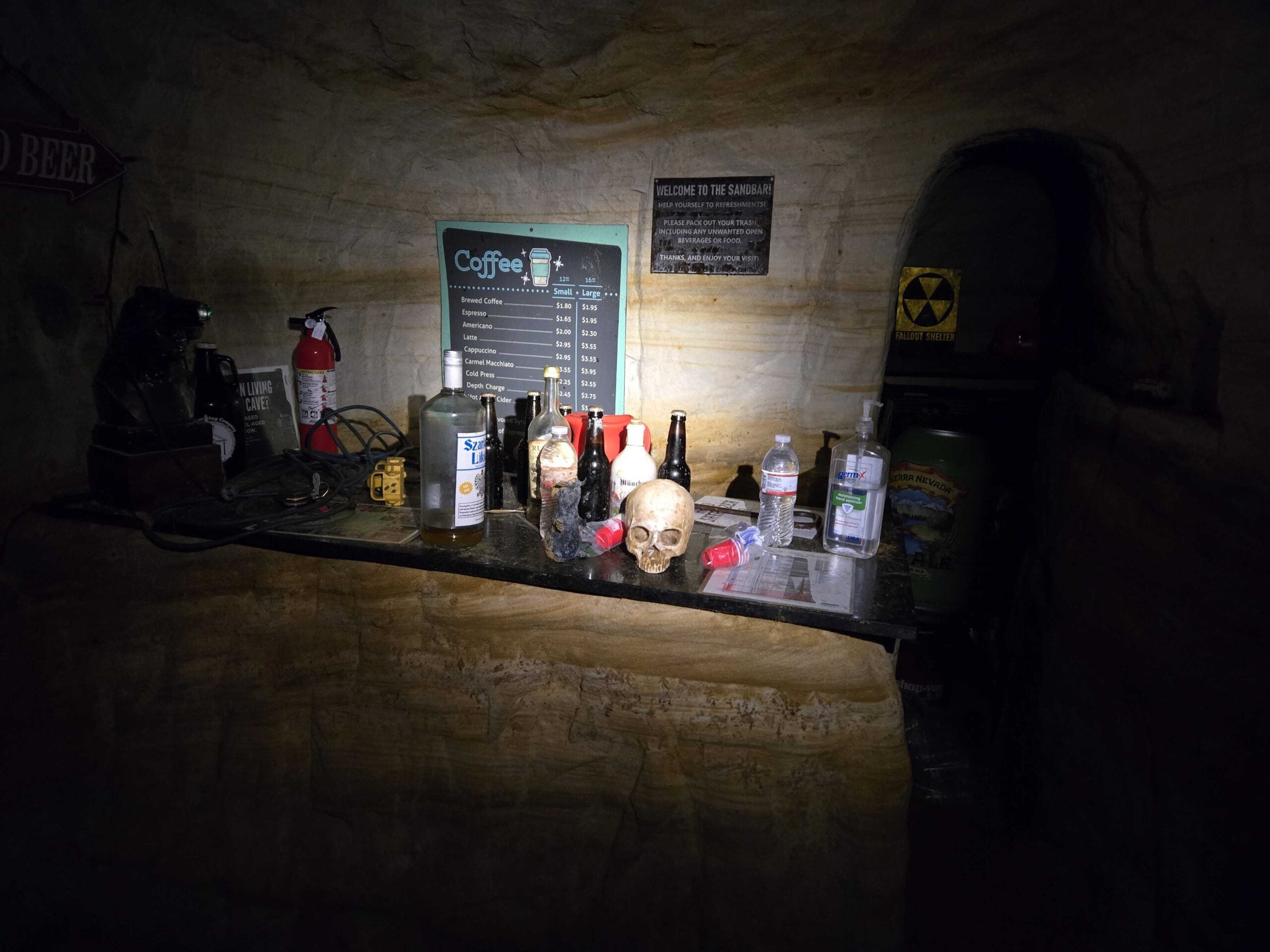

“This is Gabe’s bar,” Sutterlin reveals. “Dave and I are creating a lot of places you can move through, but we aren’t really creating anywhere as like a place to hang out and move to.”

The bar is around 15 feet in length, with nearly everything carved directly out of the sandstone. The bar on the left of the entrance and the two booths and accompanying tables on the right are solid sandstone. The floor is covered in sand. The sand grains throughout the tunnels here are bigger, more coarse than the sand you’d run into on a beach.

Time in Sandland is measured in years. Eric and his colleagues make plans for what they want to sculpt underground up to 20 years in advance.

But Dave Gerboth, the person who digs the most at Sandland, is 72. Both Gerboth and Sutterlin said they know Dave might only have a few years of digging left in him at the complex. Sutterlin himself is 44 years old and has early signs of kneecap arthritis from his years of cave exploration.

But Sutterlin said the future of Sandland goes far beyond the two of them.

“Right now, it’s me. I’m the sole member of our LLC,” Sutterlin explained. “In the long run, once I pass, it’ll be a group of our top contributors. Because they are the people that can be most trusted to stay true to our mission and not try to, for example, divert it for profit.”

Keeping true to that mission is important for Sutterlin and his colleagues, because Sandland isn’t open to the general public. Sutterlin estimated that he contributed nearly $100,000 of his own money to funding Sandland.

But, in Sutterlin’s words, they do welcome donations and visitors who reach out to Sutterlin and schedule a visit. Their website has videos detailing their complex and their ongoing projects.

“If Sandland was only going to last 30 years, we wouldn’t be digging at all. That wouldn’t be much benefit for our efforts,” Sutterlin said. “But since it’s likely to last 1,000 years, hopefully thousands, if not tens of thousands of people will get to crawl through and have this unique experience that they’ll remember for the rest of their lives. That’s a huge motivation to keep on digging and make it as exciting as we can.”