Wages for the lowest-paid workers in Wisconsin have risen faster than pay for higher earners in recent years, but workers still face challenges.

That’s according to the new “State of Working Wisconsin” report from the High Road Strategy Center, an economic think tank at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The report is released annually around Labor Day to provide insights into how workers are doing in the economy.

Wisconsin reached a new record-high for total jobs this summer and the unemployment rate has remained near historic lows.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The report said the tight labor market helped median wages in the state surge in 2023, matching the fastest single-year increase dating back to 1979. From 2022 to 2023, the inflation-adjusted median hourly wage increased by 97 cents.

From 2019 to 2023, the report says the bottom 20 percent of earners have had the strongest wage gains, growing by 8 percent in Wisconsin. Over the same period, the report said the top 20 percent saw their wages grow more modestly, up less than 1 percent.

That’s had an “equalizing” effect, reducing some inequalities, said Laura Dresser, the lead author on the report and associate director of the High Road Strategy Center.

At a virtual event Wednesday, she said it’s something that “doesn’t happen much in the U.S. economy.”

“We have an economy where people who suffer tend to, when events happen, suffer more,” she said. “This economy is so tight that it is the workers at the bottom end who are securing the greater gains, and I think that is because those workers are demanding more in individual and collective ways.”

But just because things are equalizing to some extent, Dresser said, doesn’t mean things are great.

“The bottom of the labor market has been neglected for too long, and all sorts of violations of dignity and law happen at the bottom of the labor market,” she said.

Despite some gaps shrinking, the report says there are still “pronounced” disparities in the economy.

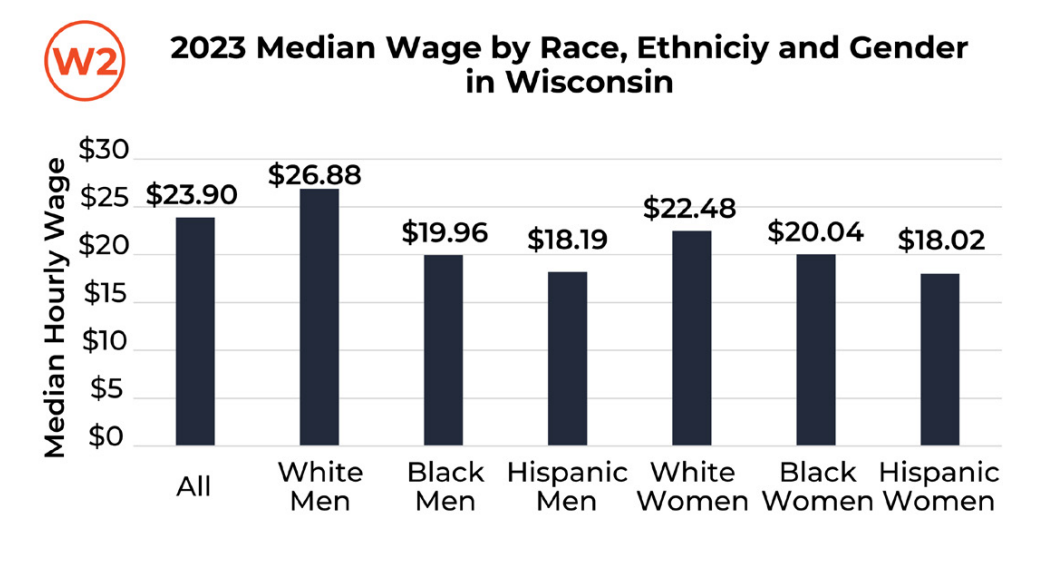

For example, the report says Black workers in Wisconsin are twice as likely to be unemployed as white workers. The report also says the median wage for white men in Wisconsin is $26.88 per hour, while it’s $22.48 for white women, $19.96 for Black men, $20.04 for Black women and $18.19 for Hispanic men.

To address those issues, the report recommends raising the minimum wage, restoring union rights and investing in child care services.

Raising the minimum wage could address racial, gender disparities

According to the report, Wisconsin’s $7.25 minimum wage disproportionately affects people of color and women. More than 379,000 Wisconsinites would get a raise if the minimum wage was increased from $7.25 an hour to $15 per hour, the report said.

Appleton resident Faith Roska, who works with the statewide policy center Kids Forward, said Wednesday that someone would need to make at least $19 per hour to live on their own without a roommate in Wisconsin.

“That’s not accounting for maybe children, maybe siblings, maybe other people that you have to take care of — $7.25 is just not feasible in any sense,” she said.

She also said the $7.25 wage makes Wisconsin less competitive with its neighbors because minimum wages are above $10 per hour in Michigan and Minnesota and $13 per hour in Illinois.

Restoring union rights in Wisconsin

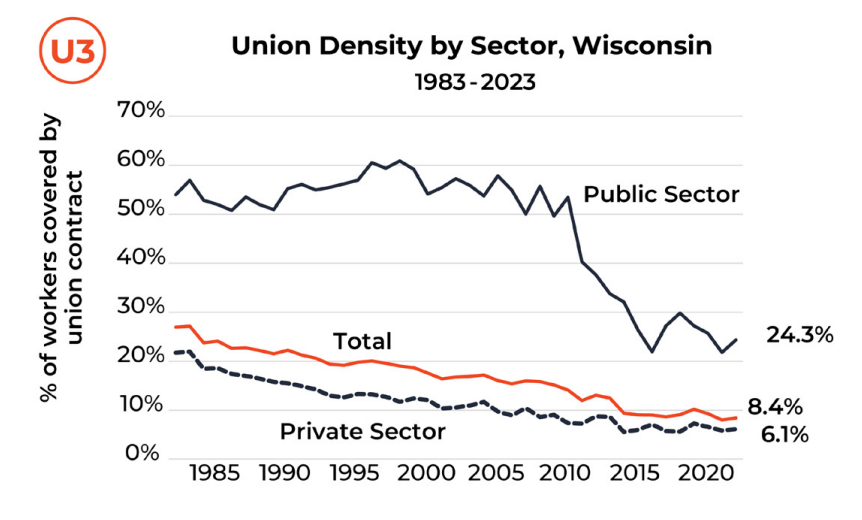

While labor union popularity has improved significantly since 2011, Wisconsin’s unionization rate has declined faster than all neighboring states, according to the report. From 2011 to 2023, the share of workers who were members of unions in the state dropped from 14 percent to 8.4 percent.

The report attributed the decline to state policies, like Act 10 and the state’s right to work law, which deter unionization in both the private and public sectors.

It called for restoring union rights to help “level the playing field” for workers and give them more power to negotiate for better wages and working conditions.

Troy Brewer, a cook at Fiserv Forum and member of the Milwaukee Area Service & Hospitality Workers union, said Wednesday that being a union member has opened his eyes to how unfairly he was treated in past service industry jobs.

“For over a quarter of a century, I worked in a place where it was like, ‘It’s my way or the highway,’” he said. “You’d ask for pay increases, and they would be like, ‘I’ll get back to you.’ Things never happened. I was treated badly.”

Investing in care

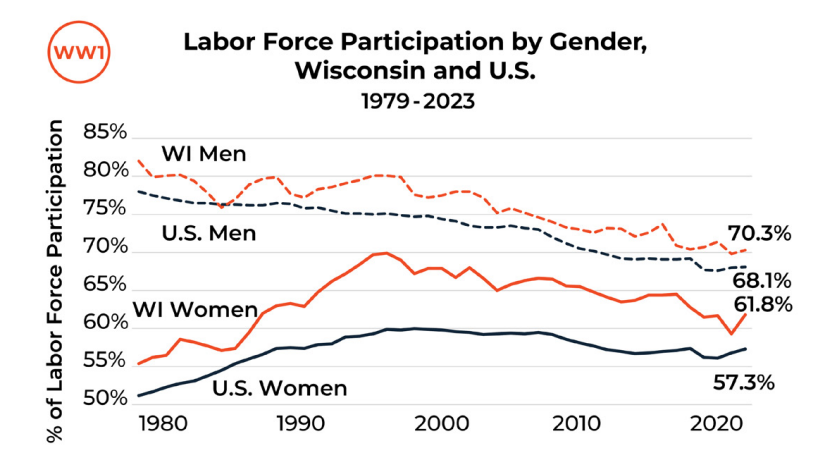

According to the report, a lack of affordable early child care forces parents to work fewer hours or leave the labor force entirely, with the burden disproportionately falling on women.

Labor force participation among women in Wisconsin has consistently outpaced that measure among women nationally, but it’s been getting narrower since 2000, the report said.

Brewer said his coworkers at the Fiserv Forum experience struggles with child care costs, and that some in the service sector often wonder, “Why would I work when child care is more than what I’m bringing home?”

The report says the state should seek to enhance investments that began during the pandemic to support child care providers to provide relief for both families and employers.

“Wisconsin needs to prioritize the development of long-term sustainable investment methods, taking inspiration from New Mexico, which is ensuring early childhood education for all families who are working, seeking work, or attending school, and who earn up to 400 percent of the federal poverty level,” the report said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.