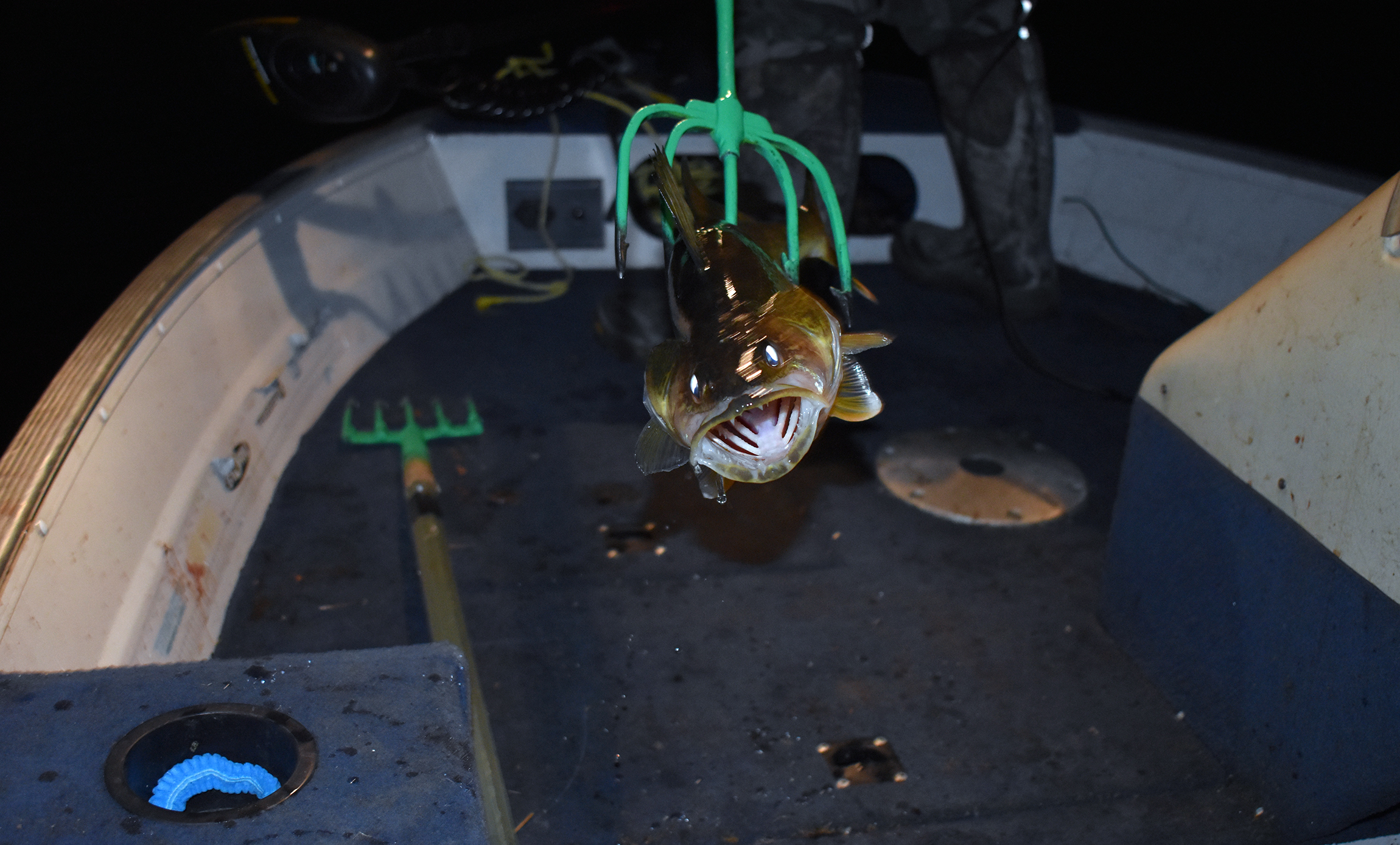

Walleye are a favorite catch for Wisconsin anglers. The fish is culturally significant to Wisconsin’s Ojibwe tribes whose communities rely on them for food. Now, a new study has found climate change is affecting their ability to thrive by disrupting when frozen lakes thaw each year.

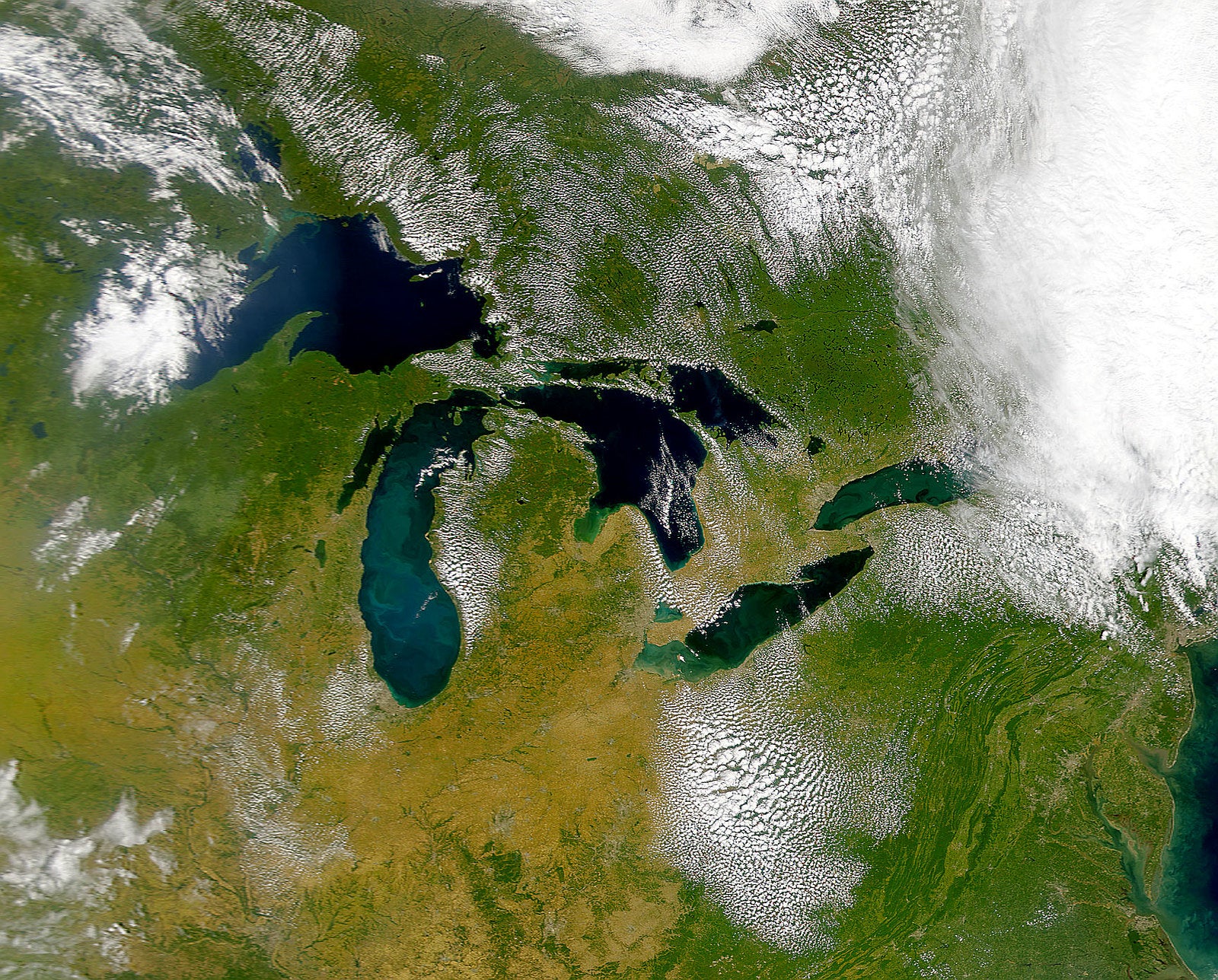

The study, published Monday in the journal Limnology and Oceanography Letters, examined 194 lakes in Wisconsin, Minnesota and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula to assess changes in walleye spawning. In the past, the spawn has been linked to the time lakes thaw each spring.

However, researchers say climate change is causing lakes to thaw earlier and about three times faster than walleye are adapting.

Martha Barta, a research technician at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said tiny plant life or organisms called phytoplankton typically bloom when the ice melts. Those are then eaten by zooplankton, which are the food source for baby walleye.

“In a year where we have a really warm spring and the ice melts really early, we can see that there’s these booms of phytoplankton and then zooplankton that occur actually before walleye hatch,” Barta said. “Then by the time that the walleye babies hatch, there’s not really a lot of food resources around for them, and survival can be really low.”

It’s not just warmer springs that are affecting walleye. Zach Feiner, a research scientist with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, said the agency is seeing more extremes in seasonal weather, and that is affecting the health of walleye populations.

“It really seems like having a normal year and average timing of spring is a prerequisite for having a boom year — a good year of walleye survival,” Feiner said. “What this means is (when) we have more and more of these extreme years, you’re just compounding more and more of these bust years for walleye. Over time, that could really imperil their ability to sustain themselves.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The study relied on data from state agencies, tribal harvests and the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission to track changes. Rob Croll, the commission’s climate change coordinator, said any environmental changes that could limit walleye populations are very concerning to Wisconsin tribes.

Walleye, or ogaa in Ojibwe, is one of the first foods used by tribal members in ceremonies along with venison, wild rice and berries. Croll said federal court cases affirming Ojibwe tribes’ treaty rights were tied to their ability to spear walleye.

Prior to federal policies and treaties that confined tribes to reservations, Croll said tribal members would move when a given food source ran out or disappeared.

“If there weren’t any walleye in this particular lake, you went to another one. Now, if climate change means that walleye is only found outside of the ceded territories, or in Canada, the tribes just can’t pick up and move and practice their rights somewhere else,” Croll said. “Those rights are legally fixed in place.”

Tribes harvest around 30,000 walleye each year in ceded territory, which covers roughly the northern third of Wisconsin. In comparison, state anglers harvest almost eight times as many fish, or 234,000 walleye, in the same region.

In the past couple decades, Feiner said, the survival of baby walleye has been on the decline.

A previous study by DNR researchers and the U.S. Geological Survey forecasted that climate change may lead to fewer walleye surviving to adulthood on the vast majority of lakes by mid-century. And walleye aren’t the only species threatened by warming waters. Other species like brook trout and brown trout are projected to lose up to 68 percent and 32 percent of their habitat respectively in the next 25 years.

“It’s possible that if you think about the landscape of fishing opportunities in Wisconsin, that’s going to change with climate change by mid-century,” Feiner said.

Most lakes in Wisconsin have a daily bag limit of three walleye per angler. However, walleye harvest is not allowed on some waters like the Minocqua Chain of Lakes in northern Wisconsin where efforts are underway to revitalize the fishery.

Feiner said controlling other stressors like the movement of invasive species and runoff that can cause algal blooms may help boost the resilience of walleye populations. He said researchers are also working to identify lakes that are “bright spots” for the species and what makes them a refuge for the cold-water fish.

Wisconsin also continues to stock around 1 million walleye fingerlings and more than 10 million fry each year, according to the DNR.

Wisconsin’s fisheries support nearly 14,000 jobs and contribute $1.9 billion to the state’s economy, according to the American Sportfishing Association.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.