Easing regulatory barriers for tribes to develop renewable energy projects would reduce disparities and potentially alleviate poverty among tribal communities, according to a new study.

A group led by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison found historic federal policies deprived tribes of lands rich in natural resources like precious metals and fossil fuels. Even so, tribes were often left with lands most favorable for wind and solar development.

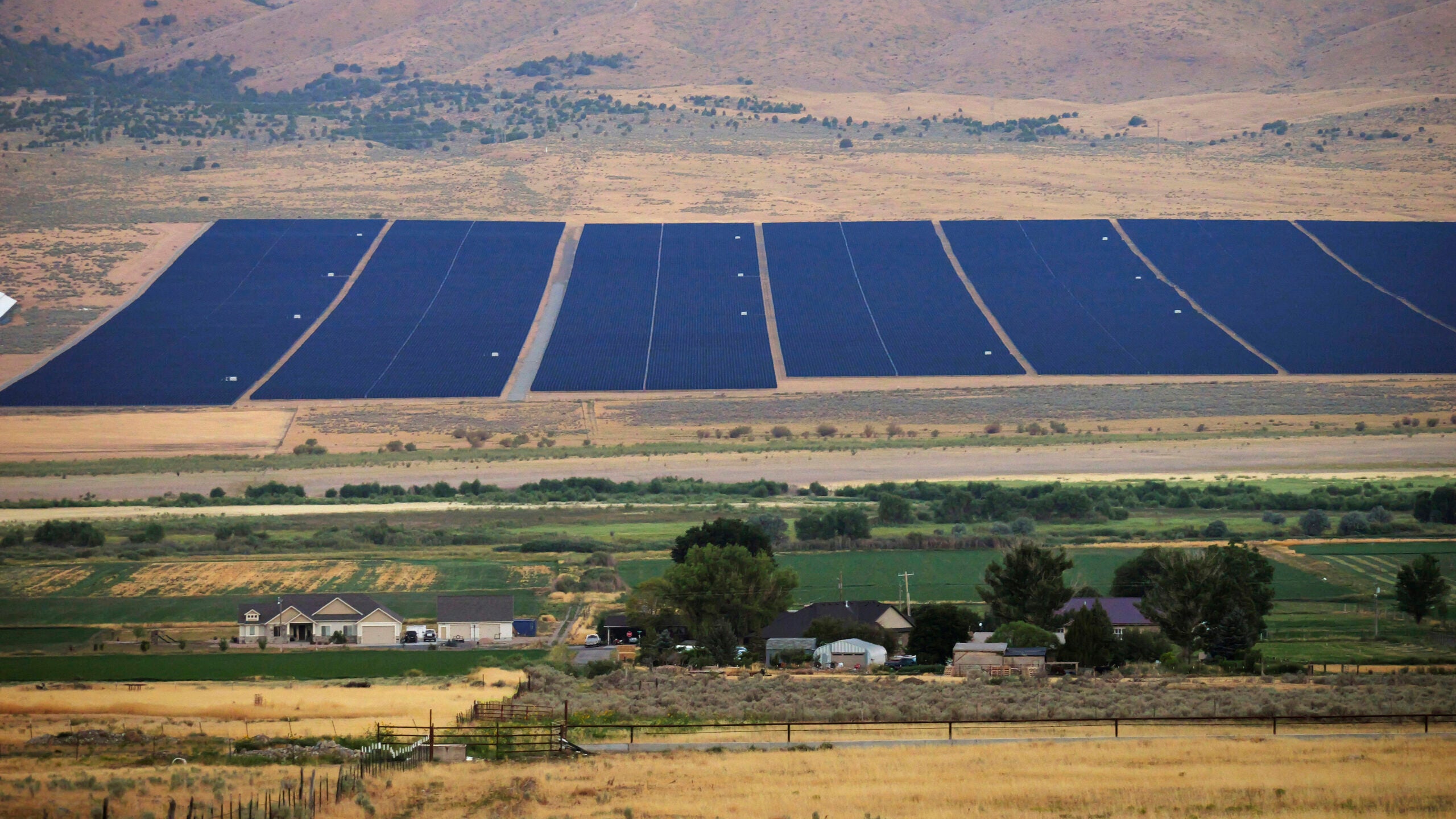

The study published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Energy found that’s especially true for the poorest 25 percent of reservations in places like South Dakota, Montana and Arizona. Despite that, reservations are 46 percent less likely to host wind farms and 110 percent less likely to host solar projects than neighboring lands, according to Dominic Parker, a professor of agricultural and applied economics at UW-Madison.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

If the disparity continues, Parker said tribes would face an economic disadvantage under increased renewable energy demand through 2050.

“Tribes and their members would forgo a lot of money that could be earned from renewable energy development,” Parker said.

Researchers used estimates of lease and tax payments that private landowners received for developing projects to forecast potential earnings for tribes and their members. Tribes would lose out on anywhere from $7 billion to $19 billion under the least and most aggressive scenarios for wind and solar growth.

Historic policies create mix of regulatory barriers on reservations

If addressed, the study’s authors contend that clean energy projects could alleviate poverty on reservations. Around 21 percent of American Indians live in poverty — the highest rate among any minority group in the nation.

The disparity in renewable development is largely due to a mix of regulatory barriers stemming from historic federal policies, such as the Dawes Act of 1887. At the time, the policy aimed to break up reservation land by allotting them to individual tribal landowners, encouraging Native Americans to become farmers. While it was later reversed, tribes lost around two-thirds of their land.

Since then, reservations have faced a mix of land ownership. That includes lands held in trust for tribes by the federal government, those owned by individual tribal members and property owned by nontribal residents.

Researchers note leases on trust land can’t be made without the involvement of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. They highlighted one instance where 49 regulatory steps were required to obtain a lease to develop oil on reservations. Sarah Johnston, an assistant professor of agricultural and applied economics, said federal oversight has posed obstacles for tribes with energy development.

“On tribal land, the amount of bureaucracy is higher,” Johnston said. “Typically, you have to work with different agencies, including the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which, anecdotally, can be quite slow in terms of getting the necessary approvals.”

Wisconsin tribe laments delays with federal agency in developing projects

The St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin have completed two rooftop solar projects along with installation of an electric vehicle charging station on the tribe’s reservation. Representative Conrad St. John, a member of the St. Croix Tribal Council, said in a statement the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Department of Interior are barriers to renewable energy development on reservations.

“In the development of any solar project on our reservation land, we have to get permission from those entities,” St. John said. “Their decision making process is often drug out unnecessarily for many years, much like our fee to trust land applications.”

The St. Croix tribe is often referred to as a “checkerboard” tribe due to its unconnected land base spanning more than four counties. Parker said the mix of land ownership on reservations creates a web of complexity for utility-scale wind and solar projects, including lands allotted to individual tribal members.

Over time, such lands were divided among surviving relatives. That means tracts are often split among many owners. The study found an average of 14 owners for such parcels.

“You have to get all the landowners on board, or at least a majority of them on board. That can be, frankly, a nightmare,” Parker said. “It could be really difficult to even find the landowners because, in some cases, the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ records of who owns lands are incomplete.”

Streamlining process could ease barriers to energy development

Researchers say allowing tribes to move through the permitting process without the approval of the Bureau of Indian Affairs or other state and local governments would make it easier for them to develop clean energy projects. However, Parker emphasized federal policies shouldn’t pressure tribes to pursue such developments or infringe on their sovereignty.

“If tribes have true sovereignty, they can develop fossil fuels. They can develop wind and solar,” Parker said.

The St. Croix tribe’s renewable energy coordinator, Jake Reynolds, said in a statement that the tribe is focused on energy sovereignty to combat pollution.

“Through all of these barriers, despite the efforts of genocide, the Tribe perseveres at the forefront of working for the benefit of all people — not just Tribal people,” Reynolds said.

The tribe said it aims to reduce energy costs, diversify casino revenues and create jobs through its solar projects.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.