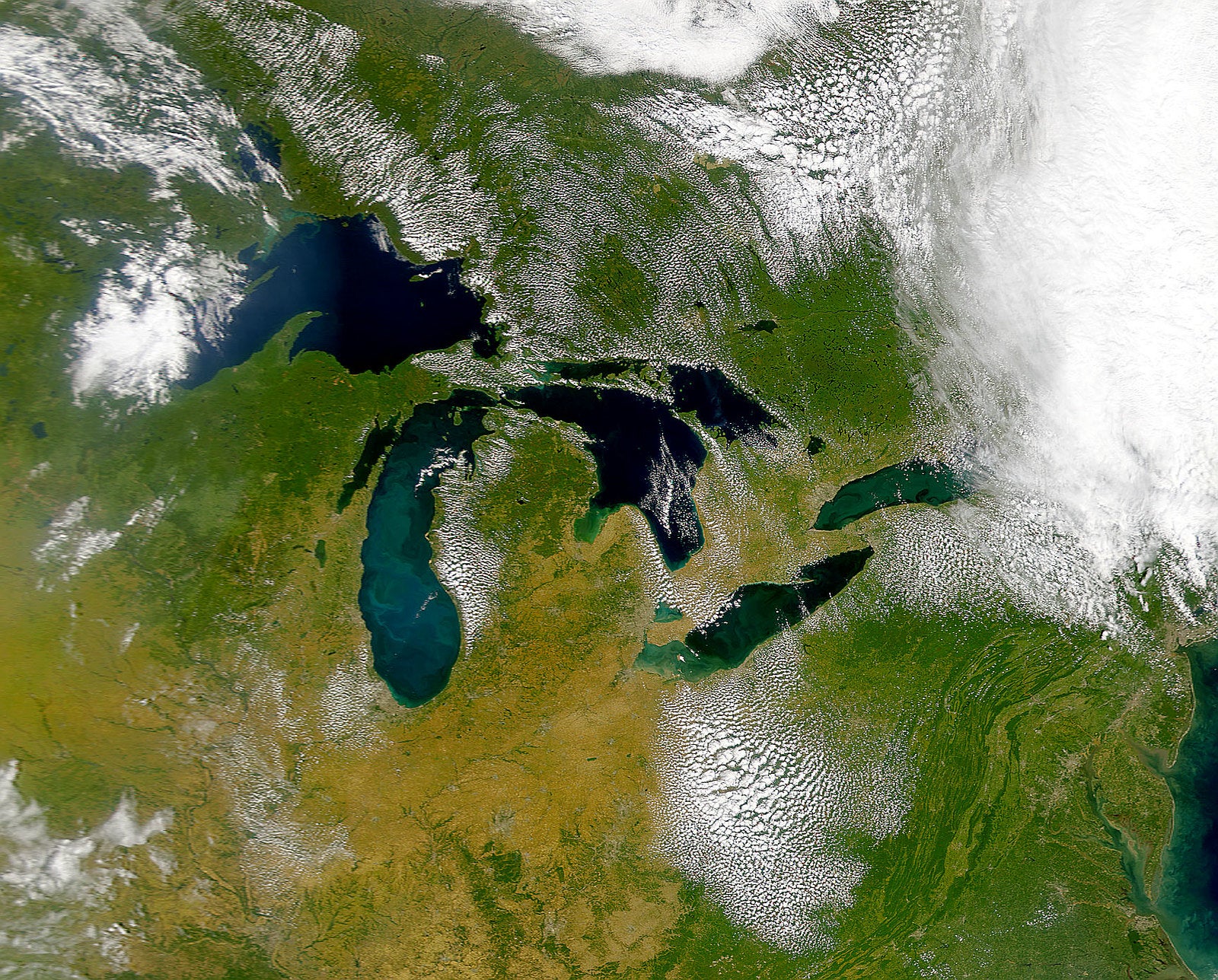

A new study builds on previous research that shows winters on the Great Lakes are growing shorter due to climate change.

The Great Lakes have been losing an average of 14 days of winter conditions each decade since 1995 due to warming air temperatures, according to the study published in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Research Letters.

The study’s lead author Eric Anderson, an environmental engineering professor with the Colorado School of Mines, said researchers arrived at their findings by examining ice conditions and surface water temperatures.

“We do see that winter time — whether you think about it in terms of ice or think about in terms of really cold water temperatures — we’re just seeing less days where those conditions exist,” Anderson said.

Research has already found the Great Lakes are losing ice cover at a rate of about 5 percent each decade for a total loss of 25 percent between 1973 and 2023. Those changes are occurring as the region has seen among the greatest increases in average winter temperatures over the past 50 years.

The study builds on that research by focusing on changes in water temperatures during the winter months. Anderson noted only Lake Erie typically sees heavy ice cover each winter, whereas the other Great Lakes often see areas of open water.

Winter is typically a blind spot for researchers due to difficulties in obtaining measurements when there’s less ice cover on the lakes. For the study, they relied largely on satellite data, as well as several monitoring stations, to examine how mixing of the lakes from top to bottom may be changing during the winter. Typically, the lakes tend to mix in the fall and spring when temperatures are the same at the top and bottom.

Winter days on the Great Lakes are being lost to spring and fall

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

During the summer, the surface of the lakes is warmer and the bottom is colder. In the winter, the opposite is true.

The study’s co-author, Craig Stow, said the reason for that is the maximum density of water is 4 degrees Celsius or about 39 degrees Fahrenheit. Stow, who is a scientist with NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab, said they found there’s been an increase in the number of spring and fall days in the lakes.

“The winter days are being lost to those spring and fall times where the temperatures are essentially the same from the very top to the very bottom,” Stow said.

Stow said that means the lakes are staying warmer in the fall and warming up earlier in the spring.

Winter days on the lakes were defined as days with ice cover or having surface temperatures of less than 2 degrees Celsius. The loss of winter days was found over nearly the entire area of Lakes Superior, Huron and Erie. In Lakes Michigan and Ontario, the loss of winter days was primarily along the shorelines and bays.

“We saw decreases in ice cover in areas where you tend to see large amounts of ice, so Green Bay and up near Beaver Island and Straits of Mackinac,” Anderson said. “We didn’t see big decreases in ice for the rest of the lake, so you didn’t have a lot of coastal ice loss along the eastern side of Wisconsin or down near Chicago.”

However, researchers did see a loss of colder temperatures in open waters around the southern shoreline of Lake Michigan, which were shifting to more days that had temperatures like spring or fall.

Lake Superior didn’t lose as many ice days as Lakes Huron or Erie because it doesn’t see as much ice cover in the middle of the lake.

“It was losing some number of days with coastal ice, particularly along the Wisconsin shoreline of Superior in the western end there,” Anderson said.

Even so, he said the lake experienced a big shift to temperatures closer to what one might expect in the spring and fall out in open waters.

Anderson and Stow said the changes could have implications for the Great Lakes in terms of extended periods when algal blooms may occur, the duration of shipping seasons, effects on the food web and the $7 billion dollar fishing industry.

“We looked at a couple decades here of change that we see you’re losing a half a month of what we used to think about being the winter,” Anderson said. “That’s really important for the chemistry of the lake. It could be important for the biology of the lake.”

Researchers say questions remain about whether the loss of winter days may stay the same or accelerate, which is one of the things they hope to examine in the future.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.