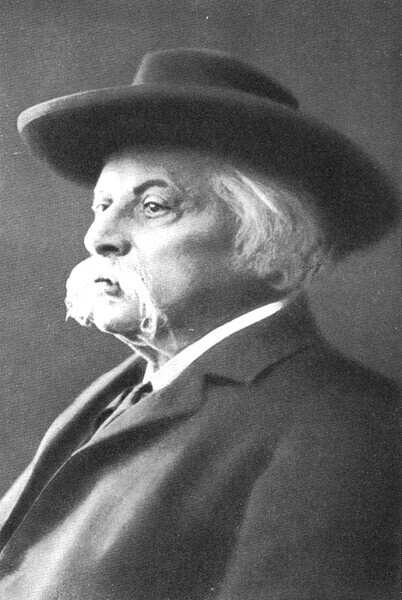

Karl Goldmark had poured his best efforts into his opera The Queen of Sheba and had high hopes for it. He was in for some shocks.

He submitted it to the Vienna Court Opera for the 1873 season. The Queen of Sheba went to the directors of the Court Opera, who took a dim view of it. They were already critics and rivals of Goldmark.

Next the opera went to the institution’s three conductors. One of them complained about its discords. The second, a frail old man, said that he was too sick to look at such a novel and difficult composition. He promptly proved his point by dying.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“I had this consolation,” Goldmark quipped. “My score was not responsible for his death.”

The third conductor liked the opera but wasn’t influential enough to push it.

Along the way, the Vienna newspapers caught wind of the opera and began to clamor for its production. Facing dwindling receipts, the Director-General of the opera, Prince Hohenlohe, decided that The Queen of Sheba might be just what the doctor ordered. Told that the director was balking at the idea of putting it on, he declared, “I will break his neck if he doesn’t produce the opera.”

It proceeded on a limited budget. By the time of the dress rehearsal the singers were worn out. The thing dragged on for four hours in a half-empty house.

“In a word,” Goldmark recalled. “The performance was as heavy as lead. Nothing seemed to go; everything we tried failed.”

The Prince asked Goldmark to come into his box. “For God’s sake,” he said, “you’ve got to chop the opera down to size. It’s impossible to produce the way it is.”

The next night Goldmark and some of the directors went to a restaurant to gather strength for the cutting. There at the table the frazzled Karl Goldmark fainted dead away.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.