An expedition is underway to find wreckage of the fighter plane flown by Wisconsin ace pilot Richard I. Bong, who shot down 40 Japanese aircraft during World War II.

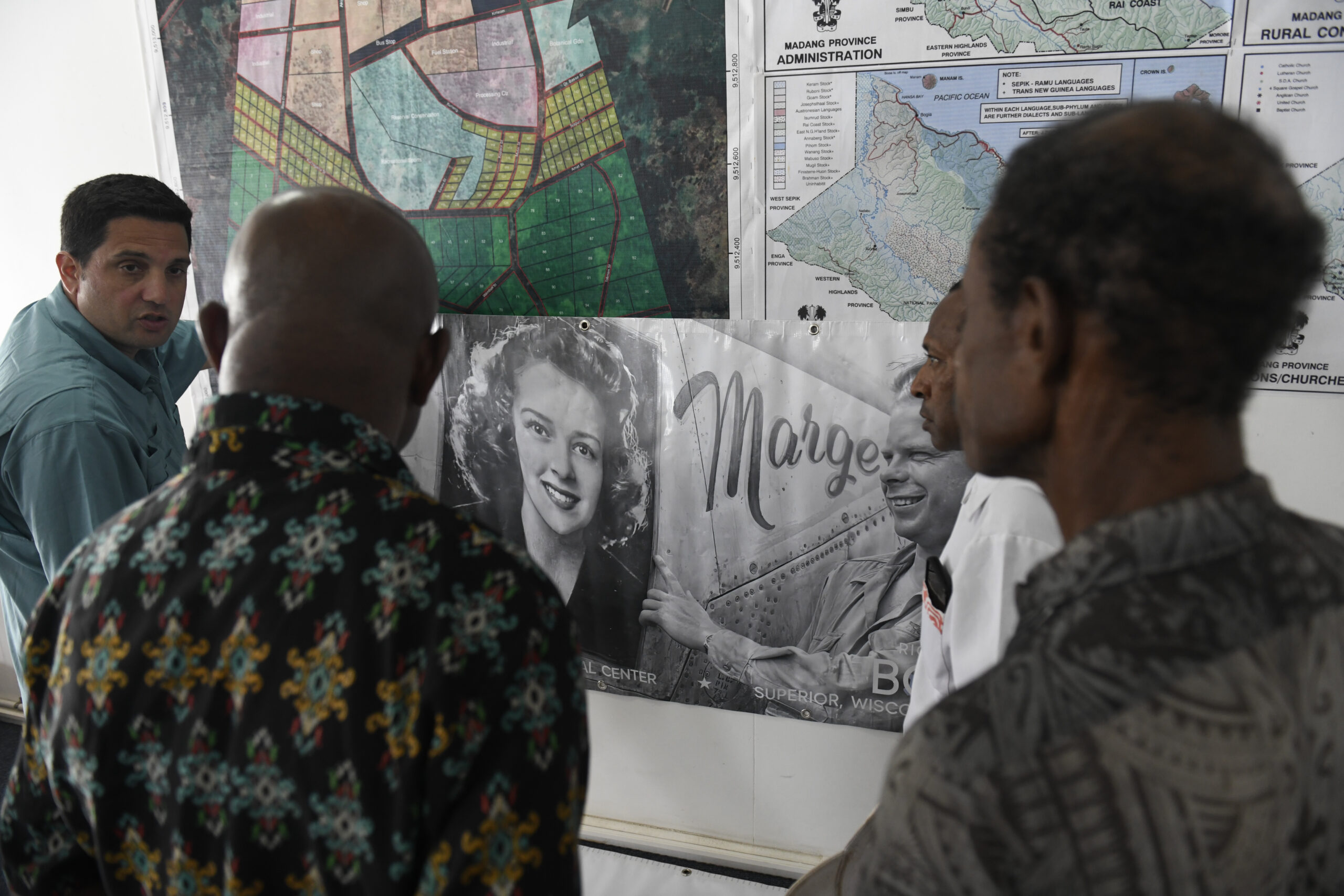

The Richard I. Bong Veterans Historical Center in Superior is partnering with the nonprofit group Pacific Wrecks to find the Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter plane in Papau New Guinea.

Briana Fiandt, curator of collections at the Bong Center, said a team began the search Tuesday along the coast of New Guinea, looking to find the primary plane Bong flew during combat in the war.

“It’s a tie to Richard Bong that is very important to, I think, the whole country,” Fiandt said. “Richard Bong was very famous in World War II. He was a national hero.”

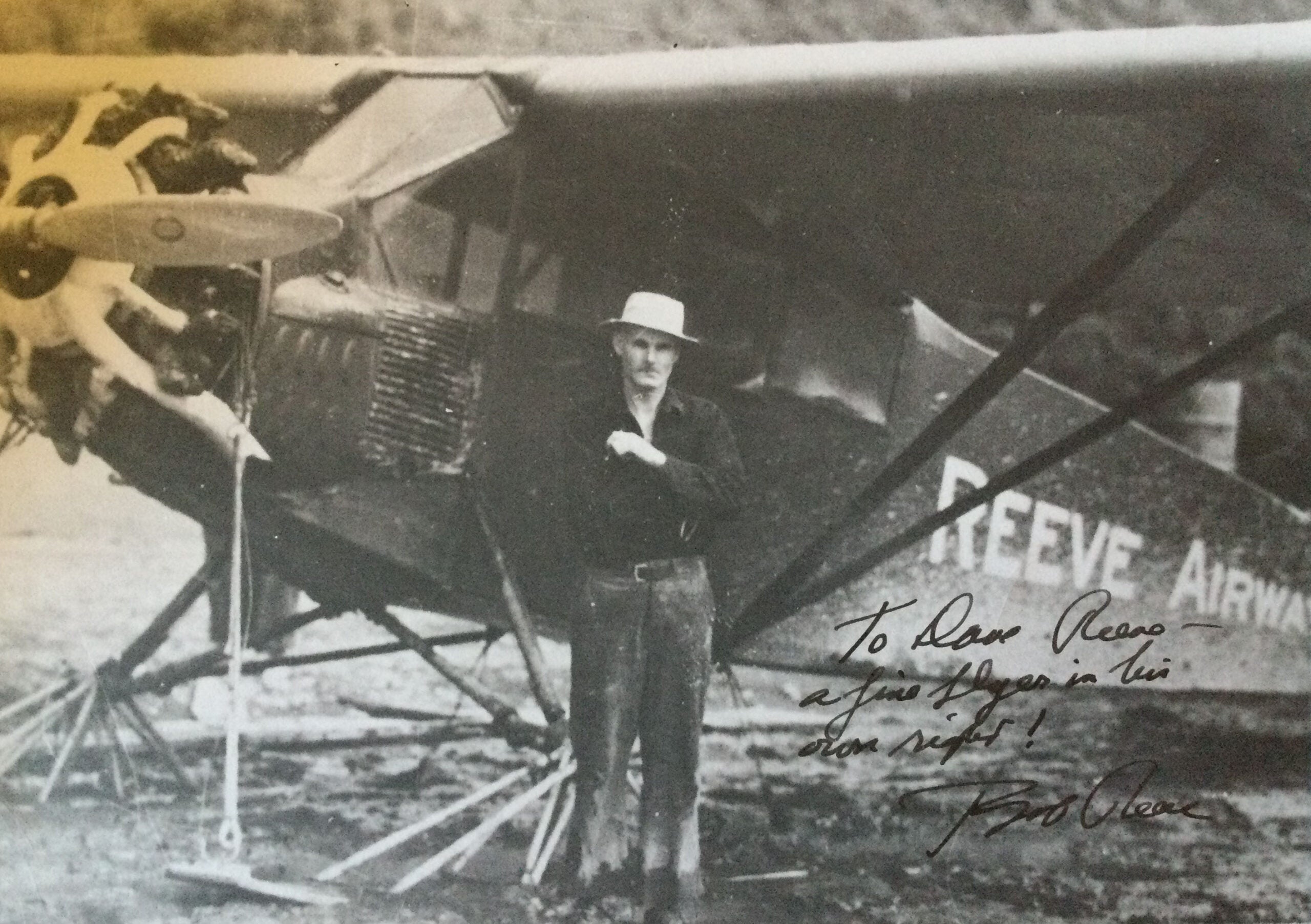

Bong shot down more planes than any other American pilot during the war. He nicknamed his twin-engine fighter “Marge” after his girlfriend, who he later married.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

In 1944, the plane malfunctioned and crashed into the jungle along the coast of Papau New Guinea as American pilot Tom Malone was flying it over the South Pacific. It was common during the war for pilots to share planes. Malone bailed out safely, and the military documented the crash.

Fiandt said Pacific Wrecks is surveying the site, hoping to find signs of Bong’s plane.

Known as the “Ace of Aces” during World War II, Bong grew up on the family farm in Poplar. According to a family member, his early interest in flying was sparked by a presidential vacation in the region.

In the summer of 1928, President Calvin Coolidge had his “Summer White House” in Superior and spent the summer fishing on the Brule River. Kathy Lehman, Bong’s niece, said she recalled hearing stories about a plane flying daily over the farm to deliver the president’s mail, fueling Bong’s desire to become a pilot.

“It was just part of our life, all of the cousins, that Uncle Dick was important. This plane was so important,” Lehman said. “It’s hard to describe how exciting this is for all of us.”

Growing up, Lehman said the school in Poplar would screen Air Force footage of her uncle every fall, and a P-38 plane was installed there until it was eventually restored as a replica of his original plane and moved to the Bong Center in Superior.

Bong enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1941, and he flew in the Pacific Theater as the Air Force pushed the Japanese back to the Philippines. While on leave, Fiandt said Bong met Marge and the two started dating.

When he returned for his second tour, she said he brought back a graduation photo of Marge that he blew up and placed on the nose of his twin-engine fighter plane.

“Most of the guys put up fairly risque nose art — provocative pictures of women and things like that,” Fiandt said. “So I think the press really liked that because it was very sweet and innocent.”

As the country tracked his exploits, Fiandt said the military eventually pulled Bong out of the war over fears of how it would affect morale if he were killed in combat.

In December 1944, General Douglas MacArthur awarded Bong the Medal of Honor. He returned home in January 1945 and married Marge in a private ceremony one month later. But Fiandt said they got married several more times for the media, adding their union was one of the top weddings of the year.

The celebrated war hero also traveled the country, selling bonds for the war effort.

That summer, Bong died in a crash while he was testing the P-80 fighter jet in California on the same day the military dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Jim Bong, his nephew, remembers his aunt talking about hearing news of his death on the radio before the family could be notified.

At the age of 26, Jim joined the Air Force and became a fighter pilot, as well. In 2003, he recalled flying a mission in Iraq and refueling while airborne, noting the tanker had a P-38 fighter plane painted on the tail.

“I wondered, ‘Is he looking down from heaven right now? Has he got my back?’” he said. “Going into combat is emotional to begin with, but to see that right in front of me while I was doing it — it made me think of him and it choked me up a little bit.”

He said some people call him the war hero’s living legacy, and the family passed Bong’s wings to him when he graduated from flight school. For him, the expedition has special meaning.

“Sometimes we get wrapped up in day-to-day life, and we forget about those who have sacrificed so much for the freedoms that we enjoy here,” Bong said. “Maybe being able to find a piece of history will reinvigorate some people’s thoughts of what’s maybe more important in life.”

He said it would be great for the family if the Pacific Wrecks team found evidence of the plane, and Lehman agreed.

“We’re so close and we have a crew that has the experience of doing this kind of thing,” Lehman said. “ I just feel like somehow they’re going to find something.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.