As the world heats up, a recent report finds summer nights are warming more than days across the globe — and even cooler states like Wisconsin are seeing more tropical nights.

The report from Climate Central, an independent group of scientists, examined the number of days where the lowest nighttime temperatures exceeded 20 and 25 degrees Celsius (68 and 77 degrees Fahrenheit) through the lens of global warming. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends keeping room temperatures around 68 degrees for a good night’s rest.

In Wisconsin, eight cities saw anywhere from 92 to 138 additional warmer nights in the last decade than they would have seen without human-induced climate change. On average, the cities ranged from between nine to 14 more hot nights per year.

State health professionals say hotter nights prevent people from getting rest and recovering from daytime heat.

“When we know that our sleep is disrupted, that really stresses our bodies out and can have all kinds of negative effects on how clearly we’re thinking and feeling stressed out,” said Anne Getzin, a Milwaukee family physician with Healthy Climate Wisconsin. “But it can also put extra stress on systems like your heart and increase chances of having a heart attack or a stroke.”

The report “Sleepless Nights” compared actual nighttime temperatures to climate models that estimate how warm nights would have been without global warming. The difference between those two numbers revealed the number of hotter nights added due to climate change.

In the last decade, the city of Madison has had 138 more hot nights than it would have experienced without climate change — the most among Wisconsin cities examined. That equates to an average of 14 more days per year. Milwaukee, the state’s largest city, had 105 more hot nights due to global warming, or an average of 11 nights per year. Over the last five years, Appleton had an average of 16 more hot nights each year.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Shel Winkley, weather and climate engagement specialist with Climate Central, said carbon emissions in the atmosphere from burning coal, natural gas and oil act like a wool blanket.

“That’s what’s helping to hold in this kind of heat, and that’s where we get those extra days of this nighttime warmth,” Winkley said.

Wisconsin climate scientists have found that the number of nights at or above 70 degrees Fahrenheit will likely quadruple by mid-century. That’s among the latest findings from Wisconsin’s Initiative on Climate Change Impacts.

State Climatologist Steve Vavrus said nighttime heat is especially problematic because there are more ways for people to cool off during the day.

“Even if people don’t have air conditioners in their homes, they can often go to a public cooling center, a library, a store, a theater (or) swimming pool to cool off during the day,” Vavrus said. “But those places are harder to find at night.”

As temperatures climb higher, Winkley said heat waves are becoming longer and more intense, compounding heat between nights and days.

“When you have these days and nights stacking day after day, then that heat really starts to build in your house,” Winkley said. “If you don’t have a proper way to get it out or cool down your house, that’s really where we start to see the biggest impact when it comes to heat illness.”

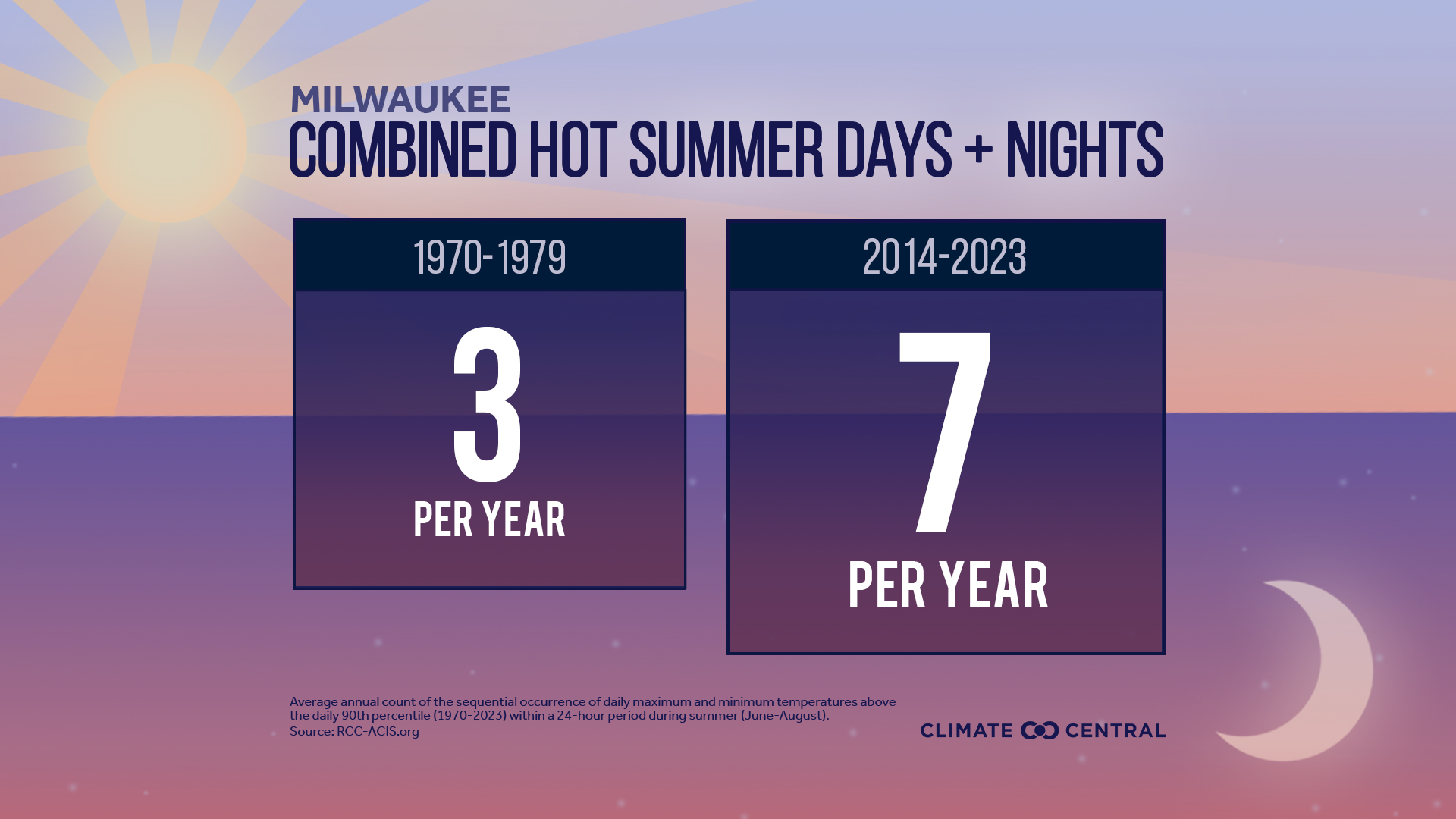

Extreme heat led to a record number of heat-related deaths last year. Since the 1970s, the combination of hot summer days and nights has occurred more often in the vast majority of 241 cities examined by Climate Central. For example, Milwaukee has seen the mix of its hottest days and nights grow from three times a year in the 1970s to seven times a year in the last decade.

Abby Novinska-Lois, executive director of Healthy Climate Wisconsin, said she ended up in a Madison emergency room for extreme heat five years ago because she didn’t have air conditioning.

“It wasn’t like just one hot day that got to me, it was the build up of four days in a row,” Novinska-Lois said.

She said communities should explore more shifts to clean energy and examine barriers that exist for vulnerable populations to access cooling centers at all times of the day. She said that includes looking at whether people are caregivers, parents or pet owners in addition to whether they have mobility issues or access to transportation.

Communities could also increase their amount of green infrastructure like trees and garden spaces that could help reduce the effect of urban heat islands. Urban areas with a lot of paved surfaces absorb more heat.

“We know that by race and income, those areas aren’t equitable,” Getzin said. “Our Black and brown communities are a lot more likely to suffer much higher temperatures.”

In the future, Getzin also pointed to a paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research that shows cooler parts of the country like Wisconsin may see more deaths among the elderly because those areas aren’t well-adapted to the heat. At the same time, the Midwest is expected to see a decrease in deaths due to a decline in very cold days due to climate change.

As temperatures rise, Getzin advised people to check on their elderly neighbors during heat waves to ensure they have everything they need to keep cool.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.