A new executive order issued by President Donald Trump Tuesday night that seeks to affect voting laws will have no impact on next week’s high-stakes state Supreme Court election in Wisconsin.

And if it survives legal scrutiny, it may have no longterm effect in Wisconsin at all, even as national election experts warn it could ultimately disenfranchise hundreds of thousands of voters — especially older people, rural residents and perhaps many married women.

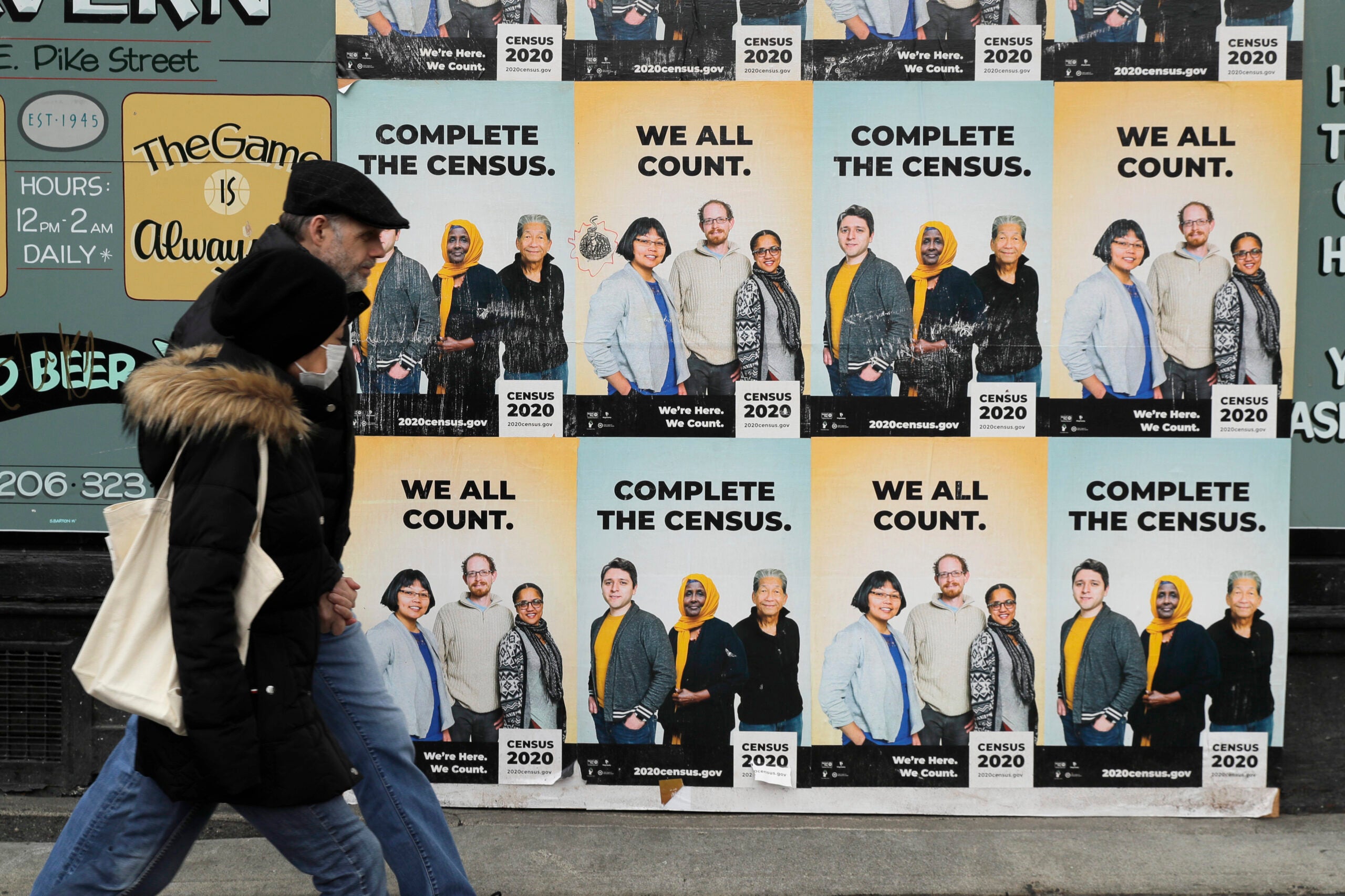

Broadly speaking, the order requires voters to show proof of citizenship to cast ballots in federal elections. It seeks to strengthen requirements set out under the National Voter Registration Act, including updating a certain form used through that process and to purge noncompliant voters.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But Wisconsin is one of six states exempt from that federal policy, stemming back from its enactment in the early 1990s. Wisconsin Elections Commission Chair Ann Jacobs, a Democrat and an attorney, argues that means “it’s possible it doesn’t affect us at all.”

Wisconsin election officials likewise don’t use the federal registration form in question. In fact, they are not allowed to, according to a decision out of the Waukesha County District Court following a lawsuit filed by the conservative Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty.

Another requirement of the order, which would withhold federal funds from states that count ballots received after election day, does not apply to Wisconsin for two reasons. Wisconsin already does not accept ballots received after election day. And it does not currently receive federal grants to support its election administration.

“The executive order is a wish list from the president to his appointees asking them to implement some policies and to the extent to which he can do that is rather limited with regards to actually affecting elections here in Wisconsin,” said Jacobs.

Next week’s election has statewide races for a Wisconsin Supreme Court seat and state superintendent and some communities also have local races. None of those statewide elections would be touched by an order about federal elections. The order also gives a timeline for going into effect that would leapfrog the spring election — even if it manages to avoid anticipated lawsuits.

Although a handful of communities allow noncitizens to vote in local elections, noncitizen voting is already illegal in all federal elections under both federal and Wisconsin state law. Voters enshrined that ban into the state constitution last November.

Instances of noncitizen voting are vanishingly rare, said Jay Heck, executive director of Common Cause Wisconsin, a voting rights group.

But he warned the arrival of the executive order, so close to a contentious state election, could sow confusion.

“There’s no provision (in the U.S. Constitution) for the president to be able to come in and unilaterally change, by executive order, how state elections are run,” Heck said.

Longer term, he said, it could disenfranchise voters who don’t have readily available proof of citizenship, like a passport or birth certificate.

Don Millis, a Republican on the Wisconsin Elections Commission and also an attorney, said he thought the order offered a chance for the state Legislature to impose a more consistent system on how Wisconsin voters prove their citizenship. State law currently requires people to self-attest to being U.S. citizens, and false claims are prosecuted as felonies.

“On the one hand, you don’t want to make it impossible or really difficult for people who can’t prove their citizens to vote. On the other hand, you want to maintain the integrity of elections,” Millis said. “There are things that could be done in the law to make an easier path for folks to show that they’re citizens, and I think that would be a good idea.”

Millis argued there’s a second reason to want to shore up how voters identify themselves as citizens. If a person is reported to a local election official as potentially committing voter fraud, it’s currently up to that official — usually a local clerk — to verify the person’s identity. That itself can be complicated during a hectic time leading up to an election, said Mills.

“I welcome the idea of being able to work with the Department of Homeland Security on helping to verify that,” he said. “But for Wisconsin, it would require a change to state law.”

Like other executive orders issued since the start of his second term, this order may be a test of Trump’s authority on voting rights. The U.S. Constitution gives broad authority to states to administer their own elections, and changes to federal law goes through Congress.

That’s led Heck to predict there will be federal lawsuits challenging this order.

Those could be on states’ rights grounds, he said. Or they could be on civil rights grounds, arguing the requirements are onerous on people, especially rural residents and elderly people, who cannot readily access the limited types of identification listed as acceptable proof of citizenship.

That list does not include birth certificates, which could themselves pose a challenge if people must seek out passports or REAL IDs.

Another unusual hiccup to verification is when a person’s name doesn’t match their birth name, as is the case for many married women who change their names, argued Jacobs, the Democratic elections commissioner.

“I also think that it sort of highlights what a hamfisted attempt this is to try to address perceived and false claims of voter fraud,” she said. “I don’t think disenfranchising married women is a good way to do that.”

Nationally, voting rights advocates argue the order is illegal because a president has no authority to tell the independent Election Assistance Commission what to do. They warn that relying on imperfect databases can disenfranchise legal citizens.

Trump’s order is the latest in a years-long effort to promote the false idea that noncitizens overwhelmingly participate in U.S. elections. Trump and his allies have argued that Democrats depend on this nonexistent voting bloc to win elections. Wisconsin elections officials have pointed to a multistep and multi-agency identification system that would prevent noncitizens from registering.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.