One of the stated goals of President Donald Trump’s use of tariffs is to restore American manufacturing jobs. But new factories could take years to come online — and in Wisconsin, the labor shortage would pose a major challenge to bringing these facilities back.

Reshoring advocates say Trump’s tariffs could help make it more cost-effective for companies to produce their products in America by making it more expensive to import. But they warn those efforts could be derailed if the state and country fail to attract more workers.

So far in his second term, Trump has imposed and threatened an array of tariffs. After dramatic declines in the stock market followed his announcement of new tariffs early this month, the president said he would pause most of them for 90 days.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

But baseline 10 percent tariffs remain in place on imports from all countries, and imports from China face a 125 percent tariff. Country-specific tariffs of varying rates are slated to take effect in July.

A tariff is a tax on goods imposed by the country that imports them. American companies that import products from abroad pay the cost, and typically pass those higher costs on to their customers in the form of higher prices.

“It’s an upfront expense,” said Buckley Brinkman, executive director of the Wisconsin Center for Manufacturing and Productivity, a public-private consulting partnership. “It’s not something that, ‘Oh, we’ll sell the goods and then pay the tariff.’ It’s a real cash flow issue.”

A survey of 153 Wisconsin employers released this winter by Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce shows 50 percent said increased tariffs would negatively affect their business, while 26 percent said it would have a positive effect and 24 percent said it would have no effect.

Companies need certainty to invest in facilities, equipment

For tariffs to work to bring back American manufacturing jobs, businesses need to believe that higher import costs will be in place for the long haul, said Harry Moser, founder of the Florida-based Reshoring Initiative.

“They need to know what tariffs will be on what, from where and for how long,” Moser said. “If there’s any chance [Trump is] going to put them on tomorrow and pull them off the next week, they say, ‘No.’”

Likewise, Brinkman said the shifting rollout of Trump’s tariffs — from being threatened to briefly implemented to paused — has made it hard for manufacturers to plan for the future.

New factories and equipment are long-term investments that comapnies expect to pay off over years, if not decades.

“If the rules keep changing, that raises the risk in any of those investments,” Brinkman said.

Kurt Bauer, president of the business lobbying group Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce, said he’s hopeful Trump can find trade agreements with many of the countries for which new tariffs are temporarily paused that level the playing field.

He said his members are especially concerned about unfair tactics that China uses to undercut American producers, including intellectual property theft and currency manipulation.

“Business is inherently uncertain and government shouldn’t make it worse,” Bauer said. “Having said that, many of our members say that this level-setting of tariffs and other costs that prevent U.S. manufacturers from exporting products abroad is necessary.”

‘There’s going to be nobody to man the factories’

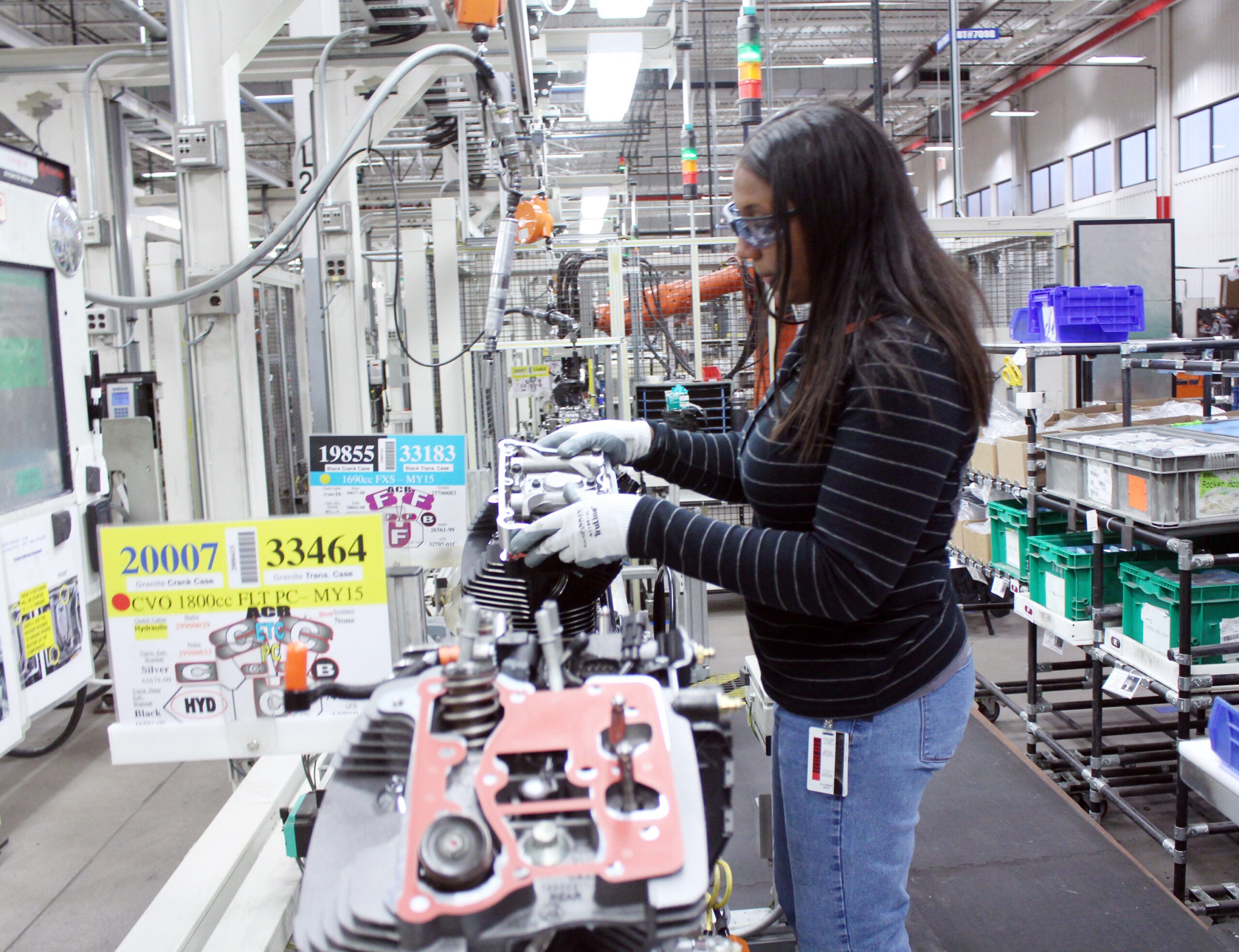

But one of the biggest barriers to bringing manufacturing back, both in Wisconsin and nationally, is a labor shortage.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce reports the latest data show there were around 1.2 million more jobs open nationally than there were unemployed workers. Wisconsin, meanwhile, has had more openings than job seekers since 2021.

Over the last decade, Moser said employers have told him the U.S. labor market is “weak, both in terms of quantity of people and quality of people.” He said there have been efforts in recent years that have helped some, pointing to high school apprenticeship programs. He says Trump’s goal of bringing manufacturing back hinges on workforce.

“If he achieves his objective, which is our objective to let’s say increase manufacturing by 40 percent — that’s 5 million workers,” Moser said. “If you don’t have the workforce, it’s not going to happen. There’s going to be nobody to man the factories.”

In Wisconsin, a 2023 research report from WMC found the state’s median age was older than the rate nationally, and warned if the population doesn’t grow at a faster rate, workforce shortages would worsen.

“We don’t have enough workers for the jobs that we have, let alone if we want to grow a job (field),” Bauer with WMC said. “This is a significant challenge.”

At the same time, Trump has promised his administration would lead a mass deportation effort and tighten immigration restrictions, efforts that could deepen labor shortages.

Bauer and Brinkman also said they would expect manufacturing that comes back to the U.S. to be very automated due to the workforce shortages and the technological advancements in the industry over the last few decades.

“One of the shoe manufacturers brought a factory back to Oregon, and the president of U.S. operations … said, ‘Yeah, we brought a bunch of manufacturing back to the U.S., but we brought very few jobs,’” Brinkman said. “Because this shoe plant was almost totally automated.”

Bringing new plants online could take years

Even if a manufacturer decides to build a new factory in Wisconsin, Bauer noted it could take anywhere from one to five years to bring a plant online.

He said it could take a year if a company already owned the land and the municipality already had zoned it for manufacturing. But often developers need to acquire land, obtain permits from multiple levels of government and then make significant investments in facilities and equipment. They may also face research and development costs.

“You’ve put all this time, energy, research into finding out where you’re going to build, what you’re going to build, and then you’ve got to make sure that you have a return on investment,” Bauer said. “Does the opportunity justify the expenses? What does the market look like for the long-term?”

While manufacturers navigate a shifting international trade landscape, the Trump administration declined to renew federal funding contracts for Manufacturing Extension Partnership programs in 10 states that help small- and medium-sized domestic manufacturers make operational improvements.

Brinkman’s organization, the Wisconsin Center for Manufacturing & Productivity, is Wisconsin’s Manufacturing Extension Partnership program. Its contract with the federal government runs through the end of the year, Brinkman said. If the contract isn’t extended, the center would lose about one-third of its funding.

The organization has helped create more than $2.5 billion in economic impact and created or retained nearly 4,000 jobs in just the past two years, according to an economic impact report.

“It’s an extremely valuable organization, and we’re a little bewildered by the president’s actions in that we’re such a key part of keeping manufacturing healthy,” Brinkman said. “To start defunding it just doesn’t make a lot of sense to us.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.