A national Alzheimer’s and dementia research study led by the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health was boosted by a $150 million grant.

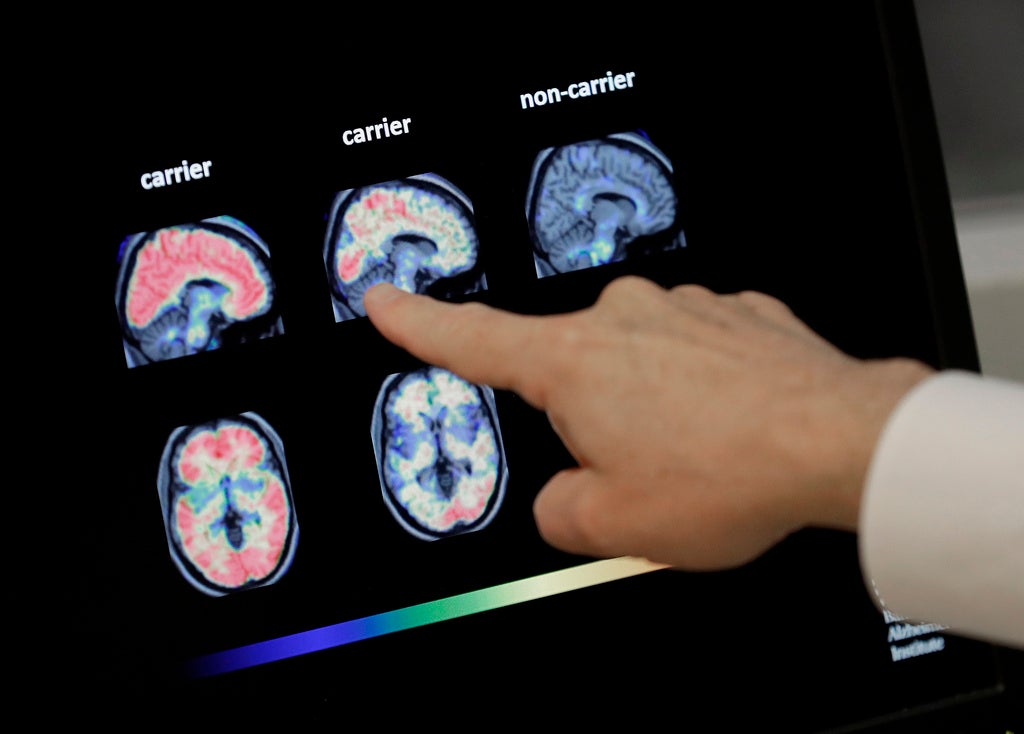

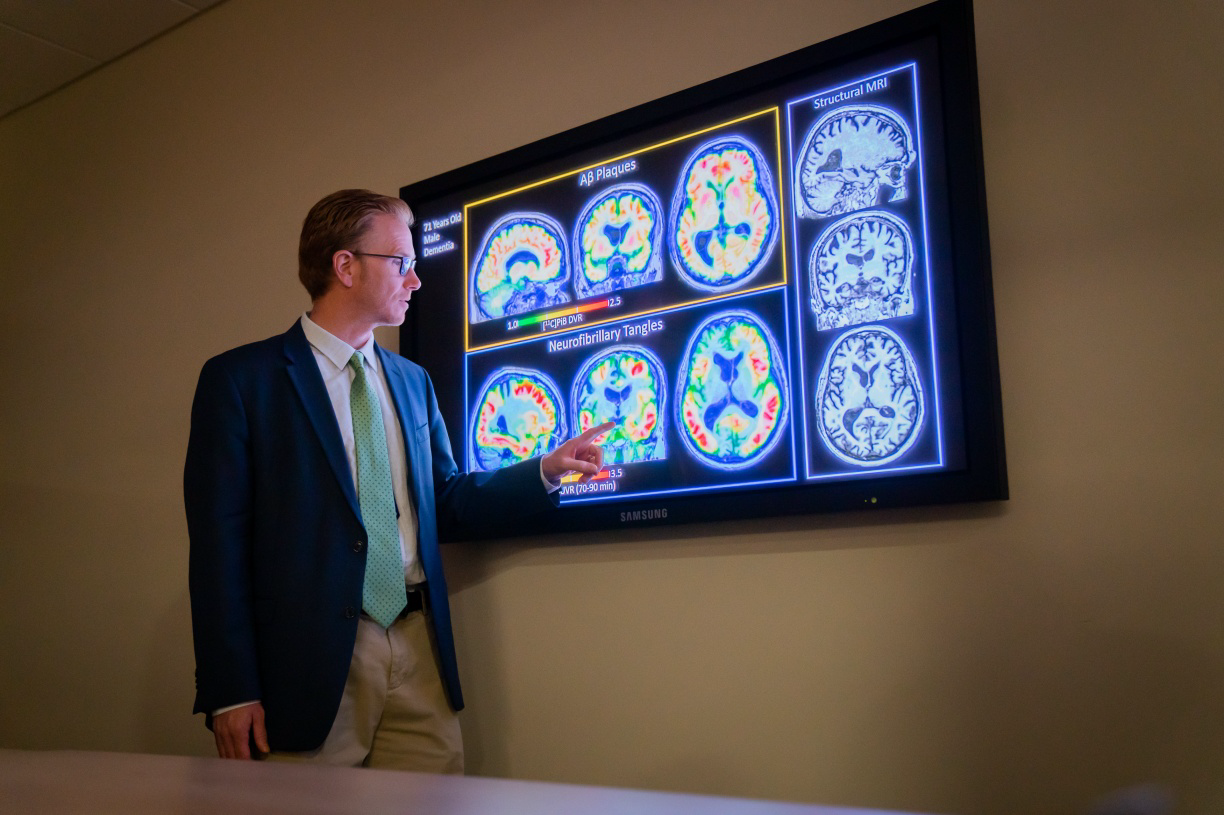

The grant from the National Institutes of Health will fund neuroimaging, particularly PET scans, to better understand Alzheimer’s and other dementias in living people. The hope is that by identifying how Alzheimer’s affects the brain, future researchers will be able to eventually prevent, slow or delay the onset of the disease and better treat its symptoms.

Alzheimer’s is a type of dementia that affects memory, thinking and behavior — and accounts for between 60 and 80 percent of dementia cases. According to the Alzheimer’s Association Wisconsin Chapter, 120,000 people in the state are living with Alzheimer’s or dementia, and more than 191,000 people care for loved ones with the disease.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The study will involve 2,000 participants nationwide over five years.

Nathaniel Chin, medical director of the study, said understanding brain changes in living people is a significant step forward. Historically, much of what researchers know about Alzheimer’s disease came from autopsies.

“It’s created this big window of opportunity, a window of intervention,” Chin said.

Participants will range from the cognitively healthy to people with diagnosed dementia. Each person will undergo imaging twice, three years apart, to measure their brain health. Chin said a range of participants is important because the disease can be present years before symptoms first appear.

“We all have skin in the game. We all are at risk of developing these changes in the brain,” Chin said. “(Our mind) is a lot of our personality, our emotions. It’s really a lot of our identity.”

John Hsiao, program director at the National Institute of Aging, said Alzheimer’s disease rarely exists alone. He said the investment in neuroimaging made possible by the research grant will lead to a better understanding of mixed dementia.

“That is the clarity that the investigators are really hoping to find,” Hsiao said.

With a better understanding, Hsiao suspects doctors will be able to say, “Here is the medicine that you can take that will turn things around or prevent things from getting worse.”

Study will standardize testing across the county

The study is a collaboration between all 37 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers in the United States. Researchers aim to standardize three tests that analyze the hallmark signs of Alzheimer’s disease. Chin said not all centers can conduct the necessary PET scans, MRI scans and blood tests. The grant from the NIH’s National Institute on Aging will change that.

“It’s this rich data collection of human beings, their lived experience and other data points,” Chin said. “But now we can tie it to the actual biology of Alzheimer’s.”

The study will allow data to be collected, shared and analyzed across the network. Hsiao said researchers will have a better understanding of an “incredibly important illness.”

“Each (center) is studying dementia. Each one is studying Alzheimer’s disease to one extent or another, or some aspect of it,” Hsiao said. “That’s why so many different centers are important and so many different investigators are important.”

‘One of the big holes we have to fill in’

In order to ensure the study and subsequent data captures the lived experiences of more people, the research team aims to recruit at least one-quarter of participants from communities historically underrepresented in research.

“One of the big holes we have to fill in is that we haven’t studied very many people that are poor. We haven’t studied very many Native Americans, African Americans, Hispanics — and we really need to do a much better job at understanding dementia in those people,” Hsiao said.

Lisa Groon, a senior health system director at the Alzheimer’s Association, wants to make sure rural residents are also included in Alzheimer’s research.

“Making sure that that farmer in the fields is having a good understanding of what brain health looks like and when it’s time to talk to a clinician about symptoms that they might be experiencing,” she said.

Chin said he hopes this study will lessen fear and stigma around Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

“We all will be experiencing changes and we all would benefit if we can find ways of staying healthy,” Chin said.

Researchers will spend the year organizing the study before participants undergo their first round of tests.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.