Pallavi Tiwari, a radiology and biomedical engineering professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, has spent the last 18 years developing artificial intelligence models to help study cancer.

Much of that work includes using machine learning to find ways to help predict cancer diagnosis, outcomes and drug responses, she said.

“We’ve been using AI machine learning approaches to identify what the overall outcomes of the patients are going to be, and then how they’re going to respond to a specific drug,” Tiwari said.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

She joined the university in 2022 to help lead an artificial intelligence initiative on campus that’s focused on health care and medical imaging.

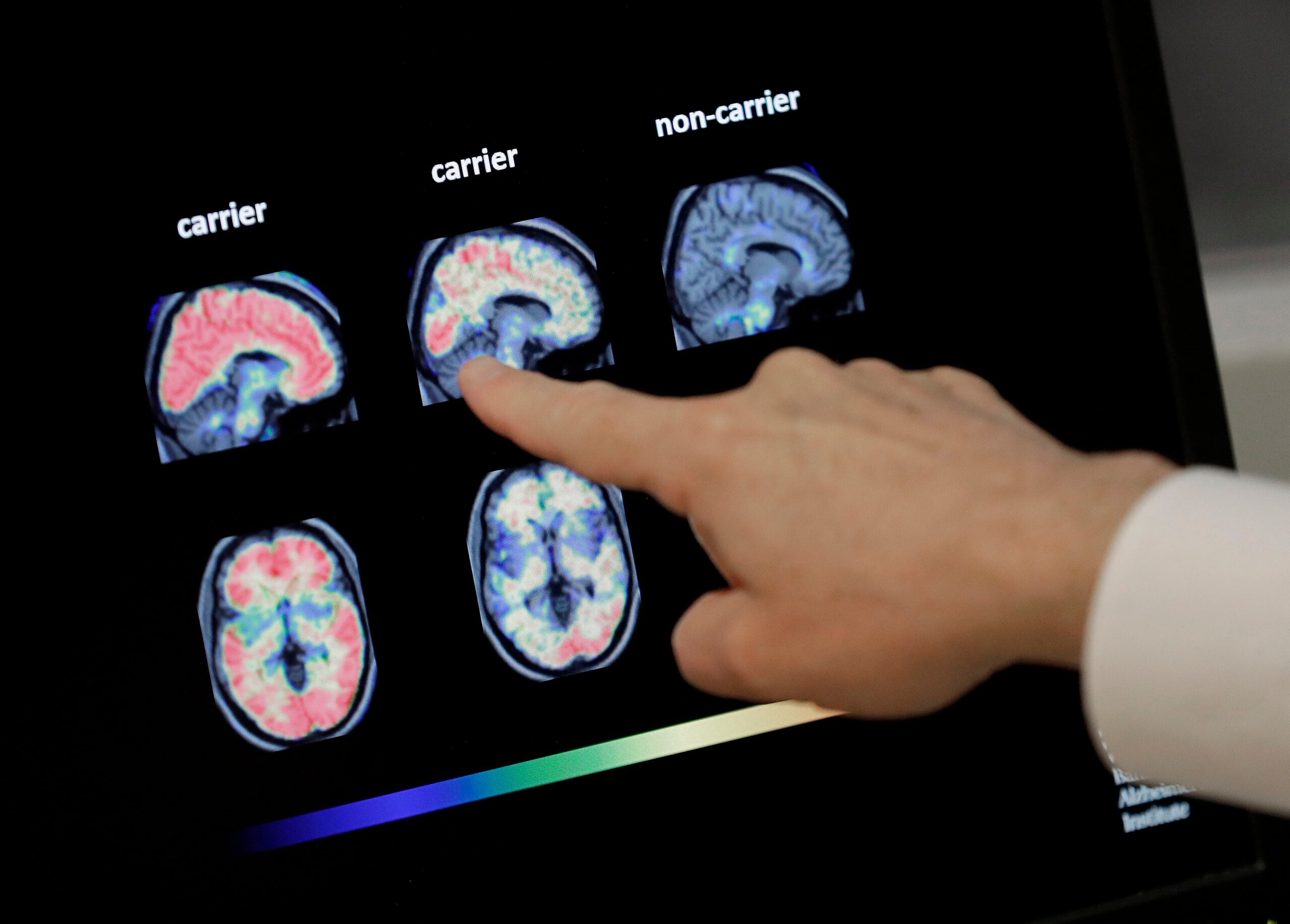

Earlier this year, Tiwari and UW-Madison researchers turned to artificial intelligence to try to learn why tumors from a lethal form of brain cancer are more aggressive in men.

This summer, they published the initial findings from a study that identified differing risk factors between men and women suffering from glioblastoma.

The research, published in the Science Advances journal, used an AI model to identify “sex specific” differences in glioblastoma tumors based on biological differences in men and women, she said. The model used data from 250 studies of glioblastoma patients to train the model to recognize the tumor’s characteristics.

“We collected data from different sites and institutions to make sure that the model is really learning patterns that are more tumor-specific, and not just sort of specific to one location or one one site,” Tiwari said. “That’s why we know that the model is robust, because it’s learning information coming from data from multiple different sides.”

Researchers were able to identify common characteristics in the tumors between men and women, but they also found some distinct differences in how the tumors behave and evolve over time, she said.

For females, higher-risk tumors were those that spread into healthy tissue. For males, the presence of certain cells around dying tissue was linked to more aggressive tumors.

“The idea here is to really start to understand the tumor characteristics, given the sex of the patient, if they’re men or women, and how we treat them,” Tiwari said. “We would imagine that the findings of this study would have implications in identifying the right population for immunotherapy or the right population for chemotherapy.”

Tiwari added that she believes artificial intelligence could be a game-changer for the medical field because there’s limits to what humans can do with all of the data that’s been acquired.

She said an AI model could hypothetically be trained with thousands of data points about how specific treatments affected patients to identify what treatments had good outcomes or bad outcomes and what other factors played a role.

That could help doctors make better decisions about how to treat their patients, Tiwari said.

“I think that can become what we call a decision support tool,” she said. “Ultimately, it’s an ally that can work with your doctor and with your oncologist to help them make better decisions, so we don’t miss a patient who has cancer (and) we don’t miss a patient who is given a treatment that they’re not going to respond to.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.