Researchers with the University of Wisconsin-Madison are looking to take 3D printing out of this world, successfully manufacturing computer components in zero gravity.

Their project, backed by NASA, aims to give future astronauts the ability to print spare parts in space.

University of Wisconsin-Madison Industrial and Systems Engineering Assistant Professor Hantang Qin told WPR that for future missions to the moon or Mars, bringing spare parts, like computer memory or critical sensors, just isn’t possible due to space limitations.

“So instead, the solution is that we make a 3D printing system that can print all the raw materials into different parts that are mandatory for space exploration,” Qin said.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Most of the technical aspects of how the machine works are shrouded in secrecy, to protect intellectual property rights. But Qin said it uses something called electrohydrodynamic, or EHD, printing. That means electrical pulses push inks made of materials like gold and silver through a tiny nozzles 30 micrometers in diameter or less. For context, that’s around the same width as a single wool fiber.

So, how does the team know whether their 3D printer will work in space? By testing it in on on a specialized jet called G-Force One during a parabolic flight full of steep climbs and descents, which reproduces zero-gravity conditions. An earlier version of the plan, used by NASA, inspired the nickname “Vomit Comet” due to the nausea the parabolic flights inspired.

Qin said the team expected there to be challenges, like the strong vibrations of the jet’s engines interfering with the printing process.

“We even rented a truck, loaded the printer into the truck and drove on different road conditions to simulate the vibration, and all the different uncertainties for when we load this into the airplane pilot zero gravity test,” Qin said.

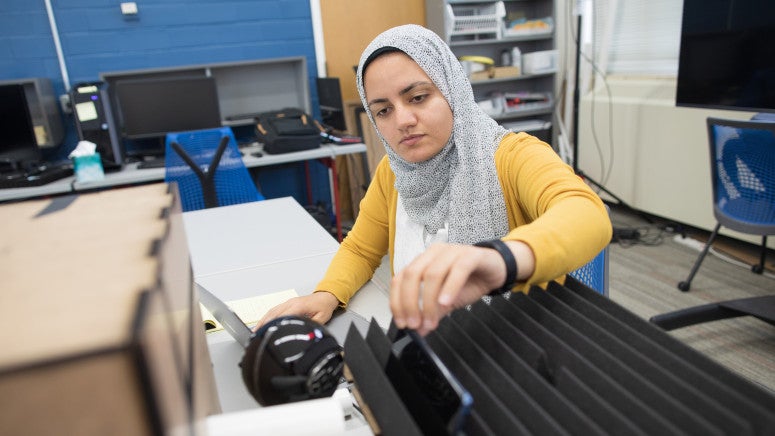

Once on G-Force One, there was another unexpected challenge. Qin said the machine’s main operator, Ph.D. student Liangkui Jaing, “got knocked out after two rounds of parabolic flight.”

Jaing told WPR he experiences motion sickness and “imagined that I may have a problem on there.” He said the pressure of making sure the printer worked during testing didn’t help.

Ph.D. student Rayne Wolf told WPR the team had to work quick when in the air. Though the flights lasted around 30 minutes, she said they were limited to 17 second intervals of zero gravity when the plane was diving. That was followed by around 30 to 40 seconds of laying on the floor with researchers and crew experiencing 2G’s of force, essentially twice normal gravity.

“So, you have to be really sharp in how you react to the system, because you really only have 17 seconds to see how the printing is performing and sort of tweak and change the different parameters in order to get the printing to work at the resolution that you want it to,” Wolf said.

Even then, because the printed circuitry is so small, researchers couldn’t verify the experiment was a success until they were back on terra firma looking through a microscope.

“I remember at that time, that was really the first sigh of relief that I had, along with the whole team,” Wolf said.

She said the highest praise came from officials with NASA, which is funding the research.

“NASA was really in awe of what we were able to accomplish up there in the amount of time given,” Wolf said. “So, that really made all of us feel like all of our hard work paid off.”

Qin said their nano-scale 3D printing technology isn’t just limited to making spare computer parts in space.

“It can also be used to make bio engineering applications, biomedical applications, to print what we call scaffolds for a new concept like tissue engineering to grow cells on top of the printed scaffolds,” Qin said.

He said he’s looking for ways to contribute to Wisconsin’s economy by teaming up with startup companies interested in the technology “to create jobs and train the workforce and mature it in the next decade.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.