Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who have studied invasive species in lakes for decades published a summary of key findings in the journal BioScience in August.

“These were the ones that we felt challenge conventional views,” said Jake Vander Zanden, director of UW–Madison’s center for limnology and lead author of the analysis. “Almost all of these were surprising to me.”

Vander Zanden helps lead a long-term research project at the center that has monitored 11 lakes in Wisconsin for over 40 years. Along with collaborators, he’s published many studies from the decades-spanning data. In their recent analysis, the authors presented broad takeaways from their past research, reasoning that understanding the proliferation and impacts of invasive species in the lakes can inform policies and management strategies.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“The long term data provides us the ability to truly understand how ecosystems are changing over time,” Vander Zanden said.

Invasive species in Wisconsin lakes have the potential to decrease water quality, harm fisheries and disrupt lake navigation — but they’re also bound to show up sometimes.

“They’re the reality of living (on) this planet,” Vander Zanden said.

And they are likely more widespread than researchers have been able to track. The analysis references a 2015 survey, which found that invasive species in Wisconsin lakes are more widespread than previously thought.

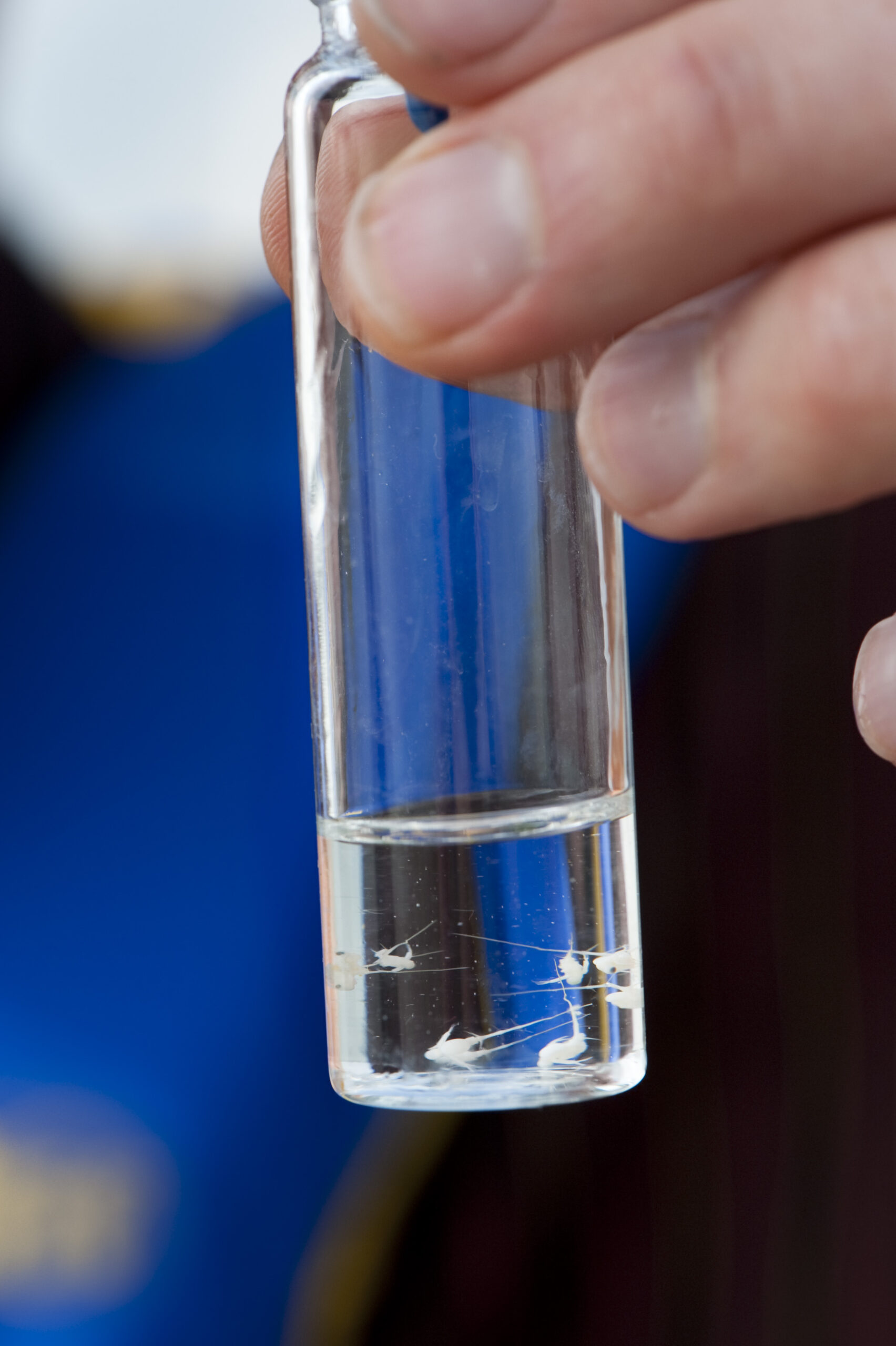

This is likely due to limited sites and resources to track them, the analysis authors said. Specifically, the survey estimated that about 39 percent of Wisconsin lakes were home to at least one of six key invasive species — rusty crayfish, spiny water flea, dreissenid mussel, Chinese mystery snail, banded mystery snail and Eurasian watermilfoil. That’s up from the previous estimate of 8 percent.

“They’re more widespread than we really know,” Vander Zanden said.

But that shouldn’t cause panic, he added.

Photo courtesy of UW-Madison University Communications

“The catch is that at many of these lakes, they’re not very abundant,” Vander Zanden said.

Often, invasive species in lakes are present at low densities, the analysis said, citing a 2013 study of aquatic populations in Hawaii, North America and Europe.

The takeaway here is that invasive species can sometimes be benign, Vander Zanden said.

“If a lake becomes invaded by an invasive species, it’s not the end of the world.” Vander Zanden said. “The ecosystems can sort of adapt to it.”

That being said, another finding in the analysis warns of times when environmental changes can trigger invasive species populations to surge to harmful levels.

Such was the case in Lake Mendota in 2009, the analysis noted. There, the invasive spiny water flea was present at low levels, a so-called “sleeper population,” until an especially cool summer in 2009. That triggered a spiny water flea outbreak in the lake, according to research on the event.

Vander Zanden worries that climate change could trigger sleeper populations in Wisconsin lakes.

“That’s a huge concern,” Vander Zanden said.

Unintended consequences of removal

The analysis presented another dichotomy.

Removing invasive species can be good for a lake, but in some cases efforts to remove the species may enact more harm than leaving them be.

The analysis highlighted a successful early 2000s removal project in Madison’s Lake Wingra. Efforts to remove invasive common carp with an enclosure and strategic fishing resulted in long-term benefits like reduced beach closures from algae blooms, the analysis said.

“We’ve learned you can push ecosystems in directions that you want to push them, and sometimes it works,” Vander Zanden said.

On the other hand, removing invasive species can have unintended consequences — for example, problems with the larger food chain. Lake Wingra had more weeds following carp removal, Vander Zanden said.

And sometimes, removal tactics can harm native species.

For example, herbicides, meant to kill invasive plants like Eurasian watermilfoil can decrease water quality and native plant populations and inadvertently hurt gamefish, according to the researchers.

“From that perspective of looking at aquatic plants, we’re experiencing more harm from the chemical treatments than we’re experiencing from the Eurasian watermilfoil itself,” Vander Zanden said.

Still, he sees the reason for chemical treatment. If left unchecked, the milfoil can choke lakes and make them difficult to navigate.

“Good is in the eye of the beholder,” Vander Zanden said.

When it comes to invasive species management, the best thing regulators can do is work to keep lakes less polluted and more resilient, Vander Zanden said.

“A key conclusion is that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to invasive species control,” the researchers concluded in their analysis.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.