University of Wisconsin-Madison sociologist Jessica Calarco believes her profession is an act of “un-gaslighting people.”

She said she wants to help others see the challenges they face in their lives as products of large social structures and forces. In particular, she said she wants women to let go of guilt they might feel when they face struggles because of the unfair burden social structures place on women.

In her new book, “Holding It Together: How Women Became America’s Safety Net,” Calarco said women are often tasked with more of the unpaid or underpaid care work that keeps the economy moving.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“My hope is that through a book like this, people will be able to better understand why people are struggling, even if (others’) circumstances are very different from their own,” she said.

Calarco surveyed and interviewed families across the country to collect stories of their struggles. She spoke with WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” about the book and her ideas for better supporting women and families.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: In the book, you describe our country as being a do-it-yourself society, where everyone is expected to solve their own problems and hardships. How does that shape how we go about our lives?

Jessica Calarco: Other countries have invested in social safety nets to help people manage risk. They use taxes and regulations, especially on wealthy people and corporations, to protect people from falling into poverty, give people a leg up in reaching economic opportunities, and ensure that everyone has the time, energy and incentive to contribute to a shared project of care. (That leaves people) to take care of their families, their homes, themselves, their communities.

In the U.S., we keep taxes low. We keep our social safety net as threadbare as possible. We tell people that if they just make good choices, they shouldn’t really need that safety net at all. Forcing people to manage all that risk on their own has really just left families and communities teetering on the edge of collapse.

We haven’t collapsed, in part because we have women holding it together and filling in the gaps, filling the kinds of low-wage jobs that are often difficult to fill for employers. (Women are) also filling in gaps in the safety net, doing the default caregiving for children, for the sick and for the elderly in our communities.

KAK: One of the stats you put in the book was that more than 70 percent of U.S. adults believe hard work alone determines who gets ahead in our society — not luck or help from other people. How does that mentality affect what you see in the safety net?

JC: I talk about this as the meritocracy myth. Many people in the U.S., in part because of the kinds of cultural messages that have been promoted in our society for decades, have come to believe that we don’t really need a social safety net because if people just work hard enough, they’ll be able to succeed no matter what kinds of challenges they face.

It’s a sticky idea because in the context of high levels of inequality like what we have in the U.S., it’s psychologically reassuring to believe that if you just work hard enough, you’ll be able to be successful. But one of the problems that comes with this kind of attitude is that it leads even people who would benefit from a stronger social safety net to decide, “Maybe we shouldn’t have that net,” because that allows them to have a sense of moral superiority over people who are a little bit worse off than they are.

KAK: Wisconsin and other states have work requirements, ensuring that people who are on certain types of welfare programs are earning income and holding a job. How does that work out? Does that lead to better employment?

JC: It usually doesn’t. Unfortunately, the research on that front shows that these kinds of work requirements typically funnel, especially low-income women, into the kinds of low-wage jobs that employers struggle to fill. This doesn’t lead to long-term, stable employment. Women often get stuck in these jobs even after they run out of eligibility for welfare.

In Wisconsin, for example, you can only be on welfare for two years at a time and only five years over the course of your lifetime. That means that many women end up struggling and stuck in these kinds of jobs because they’re the best options available to them, particularly when they’re also trying to rely on things like welfare.

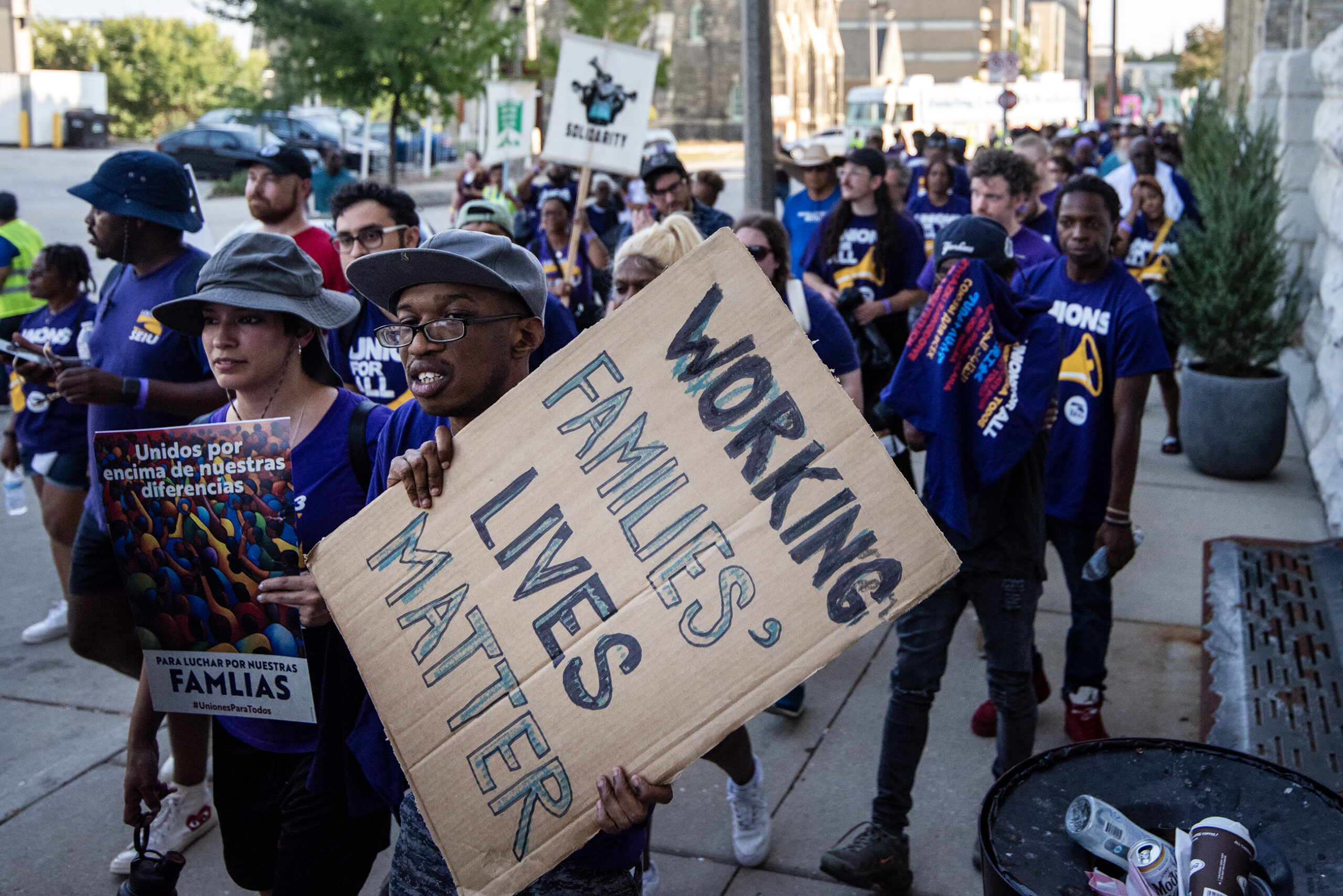

KAK: How do you see the role of organized labor factoring in here, how having right-to-work laws like those in Wisconsin affect the landscape for women and the work life and what they can earn?

JC: We know that labor unions are one of the strongest tools that we have in our arsenal to help protect workers and ensure that people not only have access to the kinds of financial resources that they need but also to make sure that they have access to the time and energy that they need to participate in the shared project of unpaid caregiving labor. We can outsource some parts of our care work, but we can’t outsource everything.

Certainly, the kinds of laws that we’ve seen — not only in Wisconsin but in many other states that have tried to chip away at union bargaining to limit the power of unions — have operated to dramatically increase inequality in those kinds of states. (Those laws) make it harder for workers to bargain, not only for better wages and better benefits, but also for the kinds of time protections that they need to be contributing more actively at home.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.