A new Milwaukee Historical Society exhibit aims to uplift the resilient stories and ideas of north side residents facing environmental challenges.

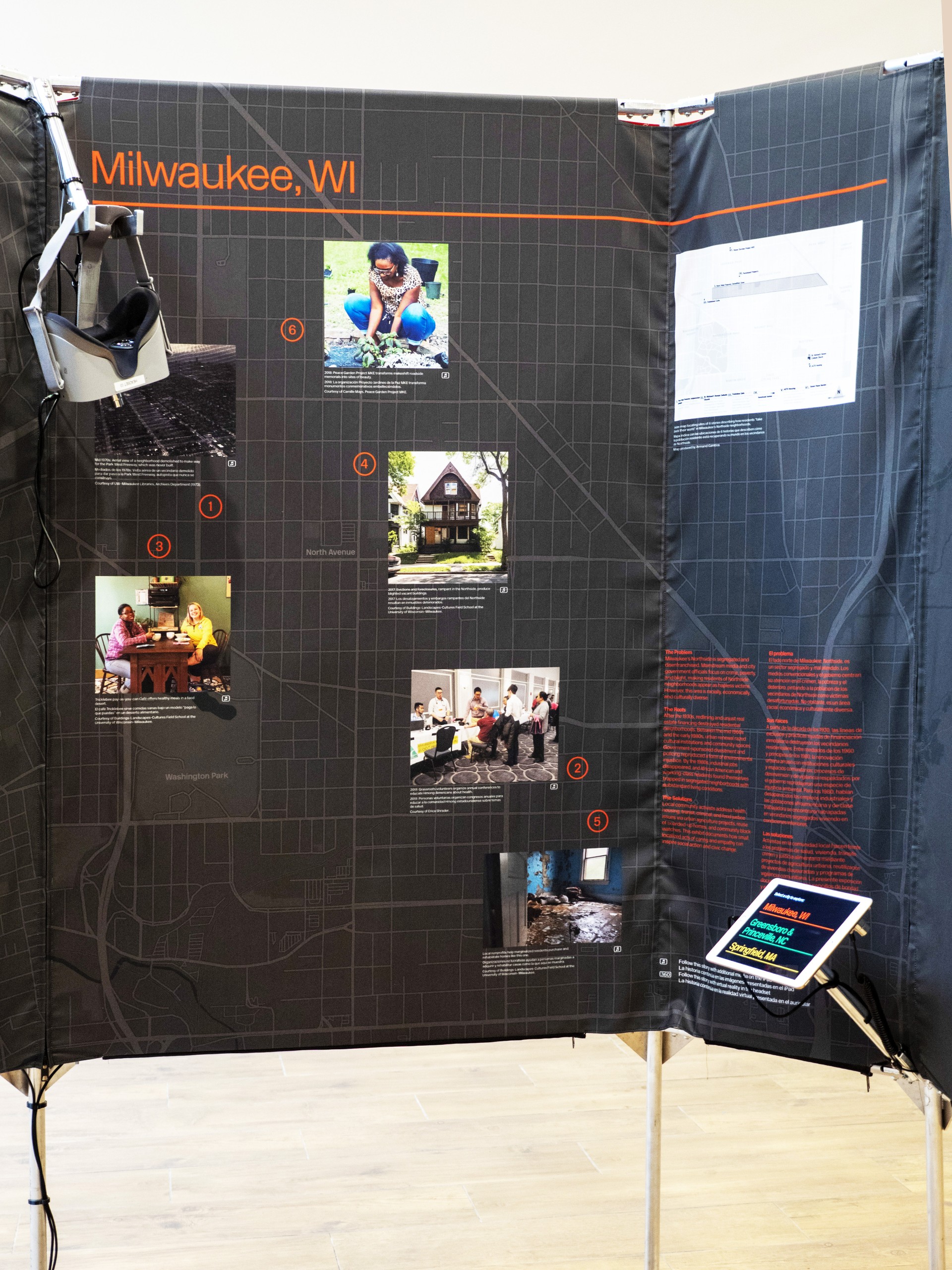

The display is part of an international traveling exhibition called “Climates of Inequality.” More than 20 communities, mostly in the contiguous United States, are featured in the exhibit, as well as communities in Mexico, Puerto Rico and Colombia.

Milwaukee’s exhibit includes written and oral stories from north side residents about lacking access to good housing and food. The stories were gathered over five years by University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee students studying buildings, landscapes and cultures.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“It’s really nice to put together community, university, and get the stories out,” said Camille Mays, a Sherman Park resident highlighted in the exhibit, during a recent interview with WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

Students involved in the collaboration learned how north side residents envision their neighborhoods and would reimagine spaces through “very creative, innovative ways to look at future plans,” Mays said.

“African Americans are dealing with a situation in terms of the climate of where they live, which is something that they didn’t create. They’ve just simply been the victims of it.”

Reggie Jackson, board chair of the Dr. James Cameron Legacy Foundation

Housing challenges

Housing stock on Milwaukee’s north side is some of the oldest in the city, according to Reggie Jackson, board chair of the Dr. James Cameron Legacy Foundation, the parent organization of America’s Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee.

As a result of decades of disinvestment from the city, north side residents have suffered from a lot of deteriorating infrastructure, Jackson said. He said Milwaukee’s African American population began to grow rapidly as factories and unions opened up to them during World War II. But by the 1970s and ’80s, those good-paying jobs started going away “and completely reversed the fortunes of people that came to Milwaukee for a better situation.”

Meanwhile, city government leaders invested more in the south and east sides of the city.

“So, African Americans are dealing with a situation in terms of the climate of where they live, which is something that they didn’t create. They’ve just simply been the victims of it,” Jackson said.

Jackson has been a community partner with UW-Milwaukee students and their work for the “Climates of Inequality” project.

“People were finally listening to (community members’) voices for the first time in their lives,” he said. “(North side residents) are really smart. They know about the problems that they face, and they have typically better solutions to those problems than policymakers who are looking to officials and other people. If only people would listen to them, I think we could make a lot more progress.”

What would Mays do?

Speaking with “Wisconsin Today,” Mays outlined several areas where she sees challenges and opportunities on the north side.

Mays said the Harambee neighborhood is experiencing some upgrades, such as new businesses and stores along 3rd Street. But those changes are creating barriers, too.

“A lot of the people who didn’t have housing equity in those neighborhoods had tax issues. They face being pushed out of their homes,” she said.

Mays proposes creating protections for elders and long-term homeowners, so they’ll be able to stay in place and afford the property taxes even as investments start to happen.

She said north side homebuyers are receiving assistance to purchase homes, but the cost of making homes livable still remains out of reach.

“What you see happening a lot is almost like a money pit situation,” Mays said.

The city of Milwaukee offers a Downpayment Assistance Program and a Homebuyer Assistance Program. The latter provides forgivable loans to people interested in rehabilitating foreclosed homes they plan to live in.

“However, the scope of work will be way beyond the loan amount,” Mays said. “Before (the city allows) the first-time homeowners program, I think somebody’s house and property should be fixed up.”

From resident to researcher

Teonna Cooksey said she saw segregation in Milwaukee firsthand while growing up on the north side and taking a bus to school on the east side.

Cooksey would see “how the city changed either through a business district, some parks or some highways,” she told “Wisconsin Today.” “And that is pretty much what prompted me to be interested in architecture and planning combined.”

She went on to study at UW-Milwaukee and gathered community stories beginning in 2016 in the Washington Park and Sherman Park neighborhoods. From that research, which fed into the “Climates of Inequality” exhibition, Cooksey also created her own project, the Women’s Empowerment Network.

“(The project) essentially looks at foreclosure and eviction, and how it affects Black women in Milwaukee,” Cooksey said.

The Women’s Empowerment Network examines “how to use design and planning techniques to create a housing typology, and to merge different strategic partnerships to create resources and utilize a housing stock that is currently vacant,” she added.

Cooksey recently finished a dual graduate degree in architecture and planning at Columbia University in New York. She plans to continue researching Milwaukee, looking at innovative solutions for the north side, such as facilitating collective property purchases or separating the price of land from buildings so the property can be more accessible to lower-income buyers.

“For me, growing up in Milwaukee, I’ve always been interested in how can I not only influence the way that the city changes but also be a part and leading in that change,” Cooksey said.

“Climates of Inequality: Stories of Environmental Justice” runs at the Milwaukee Historical Society until June 1.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.