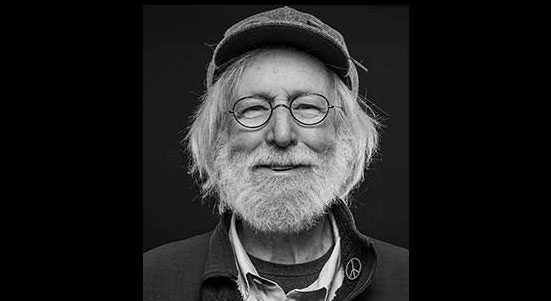

As a philosopher, John Koethe’s work requires research, discipline and logical consistency. But as a poet, those same philosophical wonders are free to wander the limits of his imagination.

Koethe, a distinguished professor emeritus of philosophy at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, shared these sentiments with WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” when discussing the recent publication of his 13th poetry book “Cemeteries and Galaxies.”

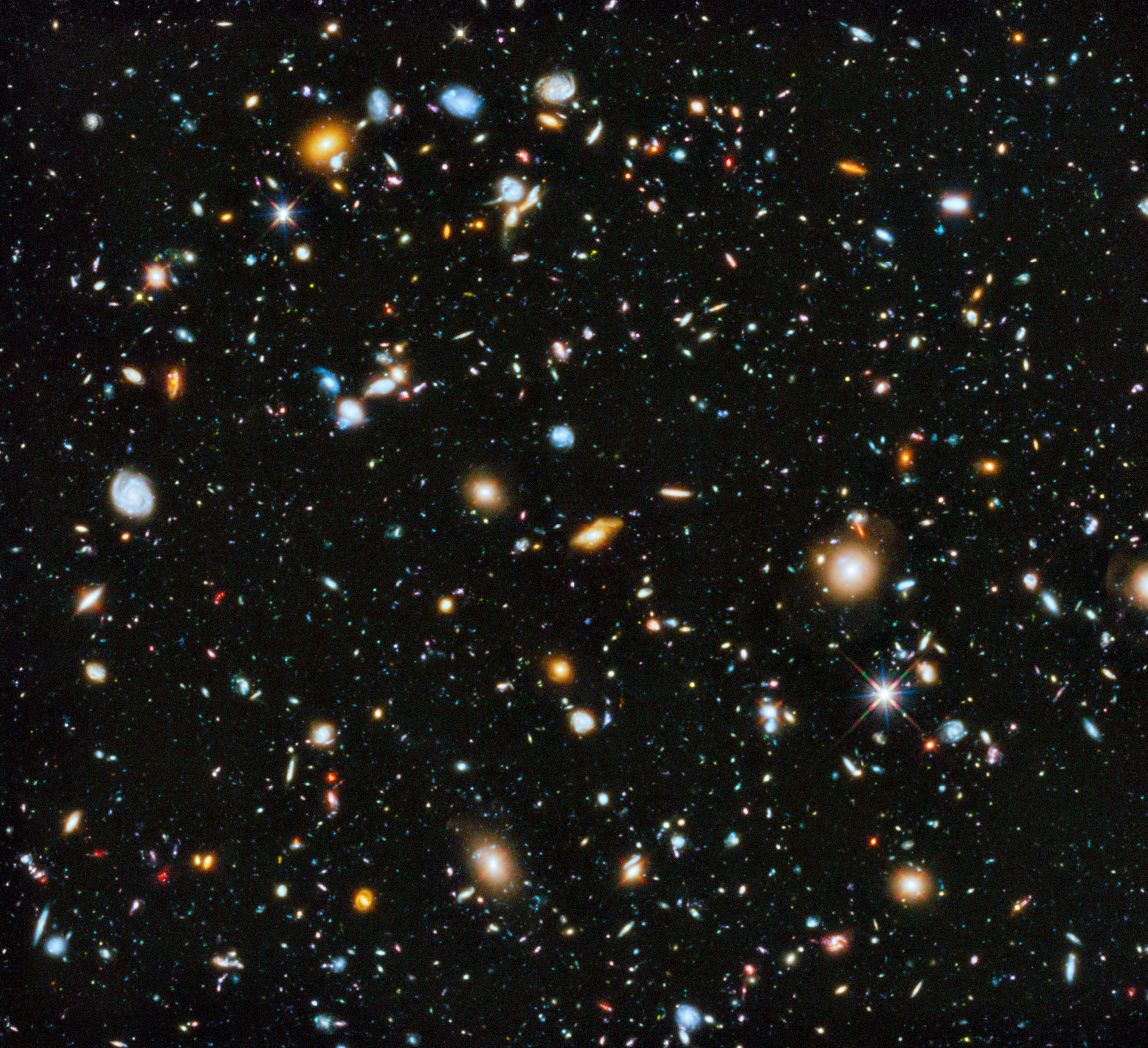

“The cemetery alludes to the privacy that we have while we’re alive and which vanishes with our death,” Koethe said about the title. “The galaxies allude to the vast, impersonal universe in which we’re situated.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

While philosophy is a throughline of all of Koethe’s poetry, he said it is also inspired by subjects like physics and math.

“I’ve always thought of physics, mathematics, poetry and then philosophy — all as different aspects of this obsession with what it’s like to have an awareness of oneself and the world and one’s relation to it,” Koethe said. “I’ve been obsessed by the modernist aspects of these various disciplines.”

Koethe will give a reading from his new book at Boswell Book Company in Milwaukee on Thursday, April 4 at 6:30 p.m.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: The first line in this book of poetry is a question: “Where did it go wrong?” And in my head, I think, “Okay, where did what go wrong, John? What do you mean?” Why did you begin with this question?

John Koethe: I feel that it’s a certain kind of disillusionment. But the poem goes on to talk about how it’s not that anything in particular went wrong — it just seems like a free-floating anxiety and disillusionment that settles in. Maybe just as you get older, or maybe it’s an artifact of our time. I’m not sure.

KAK: I appreciate how questions pop up all over your poems. When I read them, that question mark feels a little more personal, like it’s speaking to me. How do you view writing questions in your poems?

JK: I’m always wondering about things, and I’m never confident in any conclusions I draw. There’s one poem that points out that one of my favorite phrases is “and yet.” As soon as I say something, I immediately have second thoughts and start to qualify it. It’s just the cast of mind I have. My temperament is inquisitive, but I’m not so good at resolving these kinds of questions and uncertainties.

That’s really where philosophy begins. In fact, I wrote my graduate dissertation on skepticism, which is the idea that we don’t really know anything about the world. I was arguing against it, but that’s one of my main philosophical obsessions. I think that’s true of most philosophers.

KAK: You write a lot about privacy. What does privacy mean to you as an artist and a scholar?

JK: It’s the condition of human consciousness that you are acquainted with, the world of your awareness. But in some sense, it’s private to you, and you’re the only one who has access to it.

The impetus to most of my poetry is this private sense of what it’s like to be alive, that you alone have. It seems like the most special thing in the world — but of course everyone has it, so in a way, it’s also the most common thing in the world.

On the other hand, my other main work in philosophy has been [regarding] a philosopher named Ludwig Wittgenstein, who’s famous for arguing against the possibility of a language that’s entirely private. In a way, I think that’s because he himself was so susceptible to this almost solipsistic sense of privacy that all of us have.

KAK: As a reader, I’m grappling my way through along with you. I feel like we’re working through things together, from a reader’s vantage point.

JK: I’m glad you feel that way, because that’s what I try to do. I try to start with some worries, and then work through them, and change my mind about them as I go along.