After the 2022 elections, the Cudahy School Board took on a series of contentious battles over everything from bullying in schools and how to address racism to revamping literacy.

By January, the district’s superintendent, Tina Owen-Moore, had had enough.

Owen-Moore sent a two-page letter to her school board tendering her resignation — and pointing directly to the board’s actions as her reason.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I’ll be stepping away at the end of my term so that you can hopefully focus on the problems at hand, rather than trying to win some kind of political battle that I never asked to be part of,” she wrote to the board.

Owen-Moore’s resignation is just one example of recent tensions between school boards and district administrators in Wisconsin after years that have seen schools at the center of the political culture wars. In 2022, COVID-era frustrations led to big gains for Republican-backed candidates on Wisconsin school boards, especially in the Milwaukee suburbs.

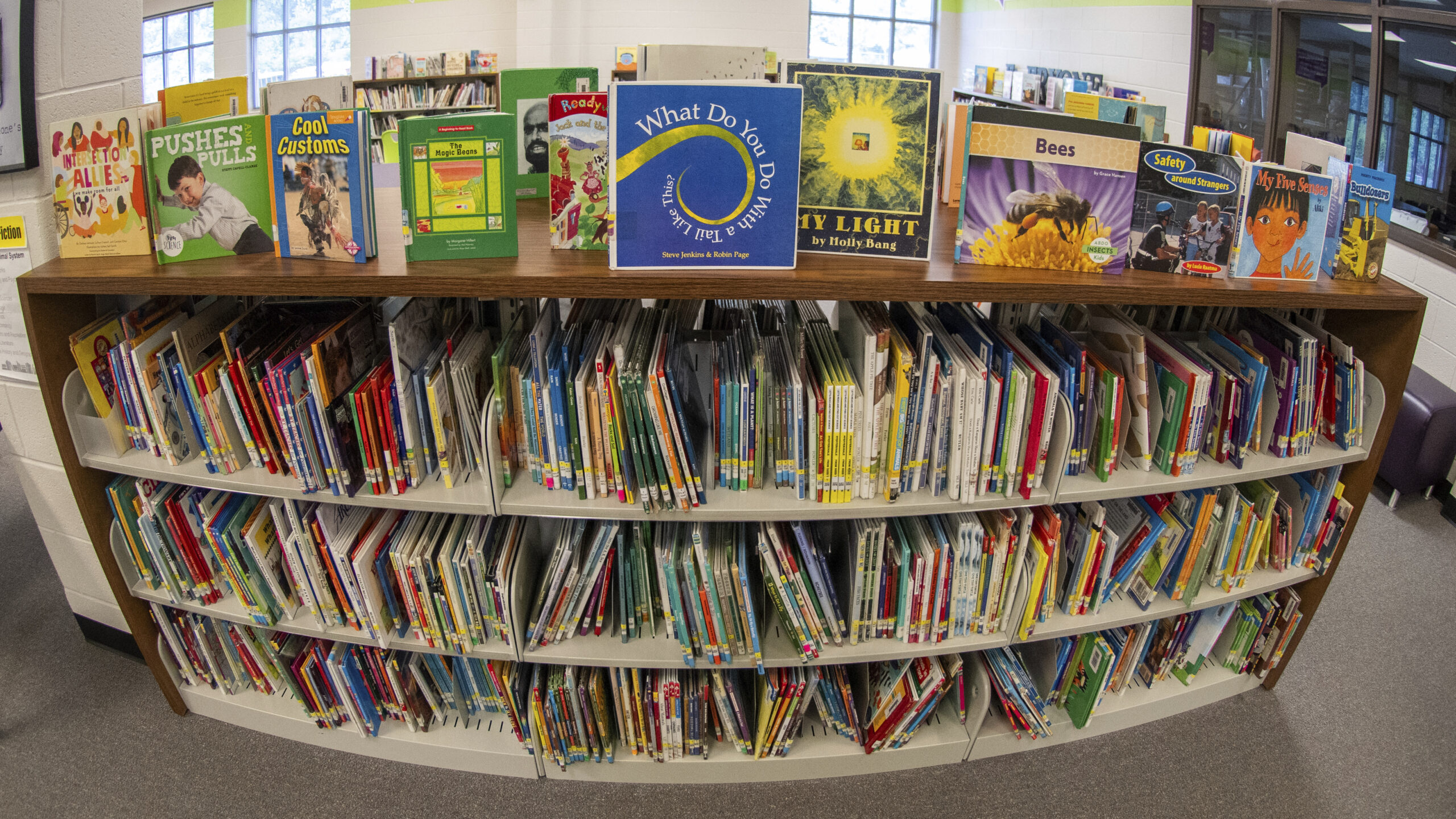

But as COVID-19 restrictions fell away, many of these boards turned to high-profile controversies, including efforts to remove books from school libraries, LGBTQ+ issues and how U.S. history is being taught.

School boards have challenged and banned books with LGBTQ+ and racial themes in the Menomonee Falls, Howard-Suamico, Waukesha, Elmbrook, Elkhorn and Kenosha Unified school districts.

In Waukesha, the school board has gotten national attention for its handling of LGBTQ+ issues.

Now, in spring elections on April 2, Wisconsin voters will have a chance to weigh in on how those new activist school boards have performed — and whether they want them to continue on this path.

Michael Ford, an associate professor of public administration at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh who studies school board races, believes culture-war issues still connect with voters.

“The partisan political parties are once again active in these nonpartisan races, and they tend to support candidates running on issues that resonate at the state and national level,” Ford said. “ Right now, those issues are cultural debates around parental rights, gender identity and diversity equity and inclusion.”

Waukesha County is a hotbed for heated races

School board races in Wisconsin are nonpartisan, but candidates are routinely backed by local political parties. Often the campaigns divide along partisan lines, with Republican-backed conservatives facing off against Democratic-backed liberals.

Ford said candidates with a political party’s backing have more ways to reach voters.

“What you’re seeing is the parties themselves, the Republicans and the Democrats, doing a lot of the mailings, the in-kind contributions, the voter lists, the door knockings,” Ford said.

In 2022, state and local Republican parties reported far outspending Democratic parties in the school board elections, investing over $70,000 in campaigns statewide, including over $30,000 in Waukesha County. Data on 2024 spending is not yet available.

Former Lt. Gov. Rebecca Kleefisch, a Republican who endorsed 48 school board candidates in 2022, is again supporting conservative candidates.

In an op-ed, she said, “Wisconsin kids need school boards allied with parent advocates who care more about scoring scholarly achievements than political points.”

Kleefisch’s sentiment is similar to what conservative groups have promoted: parents need more say in their children’s education.

In a statement to WPR, Kleefisch said parents should be encouraged to do everything from volunteer in their kids’ classrooms to run for school board to support their students.

“It’s when parents are not involved that we see a disconnect and sometimes even tension between education systems and families,” she said. “Conservative candidates want school districts to be responsible with spending, respectful of parents’ rights to raise their children, and aspirational on academic standards. When you take politics out of the classroom, schools can actually focus on the business of teaching.”

In Waukesha County this year, conservative candidates are backed by WisRed, an arm of the Republican Party of Waukesha County, that has endorsed in more than 20 races.

The Waukesha School Board currently has five candidates running for three seats. Three candidates are supported by WisRed, two are endorsed by Blue Sky Waukesha, which defines itself as “a place for progressives, liberals, and independents in crucial Waukesha County.”

Depending on who is elected, the nine-member board could have eight WisRed-endorsed candidates.

WisRed is also paying close attention to the Elmbrook School District, where it has a chance to tip the board to a conservative district.

Arrowhead, Hartland-Lakeside, Merton and Stone Bank school boards are in similar situations.

WisRed did not reply to requests for comment.

School board turnover could lead to superintendent exodus

Owen-Moore’s decision to leave Cudahy was notable because of the unusually direct language of her resignation letter. She declined an interview request.

Owen-Moore joined the 2,000-student school district, located about 10 miles south of Milwaukee, in July 2020. Her resignation came after the Harvard-educated school leader led the district as an early adopter of the literacy reform efforts now happening statewide.

In her January letter to school board members, she said she had hoped they could put their political differences aside through “hard work, integrity and a student focus.” That wasn’t the case. Her last day will be June 30.

“You’re not going to be able to attract people when the last superintendent was run out based on partisan issues.”

Michael Ford

Like many other districts, Cudahy is facing financial uncertainty. For years, the district considered merging the middle and high school, and keeping sixth graders at the elementary school to cut costs.

The idea was championed by Owen-Moore and approved by the board — but later revoked, a decision Owen-Moore called “disheartening.”

“The board’s … decision leaves us less able to keep programs that serve students, less able to avoid staff layoffs, and less able to provide the fair compensation that our teachers, administrators and support staff so rightly deserve,” Owen-Moore wrote.

Another Cudahy school leader who was fed up with district politics is school board member Laurie Ozbolt. After one term on the board, Ozbolt decided not to seek reelection. She said the decision was both personal and political.

Ozbolt said as a progressive board member, she also felt blind-sided by the board’s merger flip-flop. She said she felt powerless to enact the changes she supported to improve the district both financially and educationally. And she said the tone of many board meetings was unusually personal, reflecting a lack of trust from the board’s majority in Owen-Moore.

“Our meetings grew contentious, and I was angered by the way some of the board members treated our superintendent,” Ozbolt said. “Some members of the board overstepped their involvement in the day-to-day running of the school district rather than sticking to their role as policy makers. This environment and treatment of the superintendent ultimately led to my decision not to run this term.”

Ford said anyone who cares about good governance should see what happened in Cudahy as a cautionary tale.

“Especially in communities that are pretty ideologically divided, where the pendulum is going to swing every two years, you’re not going to have continuity of leadership,” Ford said. “You’re not going to be able to attract people when the last superintendent was run out based on partisan issues.”

School finances likely to be top of mind for voters

Charles Franklin, professor of law and public policy and director of the Marquette Law School Poll, said while there has been a rise of hot-button issues including book banning and critical race theory, he’s unclear if those topics are resonating with voters.

“It’s really striking how many referenda we have,” Franklin said. “And that’s really the meat and potatoes of school politics — how much and when to fund it.”

Milwaukee voters will be asked to approve a $252 million referendum this spring, which has gotten a lot of attention because of the amount. But 91 schools from 84 different districts have referenda on the ballot.

School districts across Wisconsin have been operating within state revenue limits that have not kept up with inflation. At the same time, many districts have lost students.

Since 2016, school districts have increasingly turned to referenda asking voters to increase local property taxes beyond their revenue limits.

Of Wisconsin’s 434 unique school districts, 82 percent have sought a referendum, according to a recent report from Forward Analytics, the research division of the Wisconsin Counties Association

Jason Stein, vice president and research director with the Wisconsin Policy Forum, thinks voters are going to be concerned with their school district’s finances, and how that could affect learning.

“If there are districts where there is a big referendum, or a closure of an elementary school on the table, that is a big thing that I would expect to get a healthy share of the conversation,” Stein said.

The Green Bay School Board has voted to close three schools. The Wauwatosa School District is considering closing two elementary schools.

As school districts put together their 2025 budgets without federal COVID-19 relief dollars that will expire in September, more tough choices will have to be made, Stein said.

Franklin doesn’t see school closings as an immediate issue, but he says there aren’t many 6-year-olds in the state. And that means, in 10 years, there won’t be many children in high school.

“I do think those are pretty important issues,” Franklin said. “Whether they are at the forefront of voters’ minds, is a question.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.