As a pilot with more than 30 years of experience flying for American Airlines, Capt. Dennis Tajer knows that turbulence can be quite terrifying for passengers.

And although heavy turbulence might make a plane feel like it is about to shake apart, Tajer recently told listeners of WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” that planes are built to handle heavy turbulence.

“The aircraft are designed in a way to endure turbulence that is beyond your wildest imagination,” said Tajer, who is based in Chicago and regularly flies over Wisconsin. “We’ve got a lot more going for us nowadays with technology, but the most critical piece of technology is that seat belt connected to you. If the airplane can handle it, and you’re attached to the airplane, it’s going to be unnerving, but you’re going to come out of it unharmed and maybe just have a story to tell versus a hospital visit.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Scientists say that turbulence is on the rise and expected to keep increasing because of climate change. Severe turbulence was blamed for the death of a 73-year-old man on a flight from London to Singapore in May. A dozen others were also injured during the flight.

Tajer — who is a spokesperson for the Allied Pilots Association, which represents 15,000 airline pilots — explained to “Wisconsin Today” how pilots deal with turbulence, how technology helps them and gave recommendations for maintaining the nation’s aging airline fleet.

The following has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: Is it more difficult at all to control a plane when you’re flying through turbulence?

Dennis Tajer: It can be. Moderate turbulence is uncomfortable. Everyone knows it. Maybe the captain comes on and says, “Hey, the ride’s going to be uncomfortable here for a little bit.”

It’s the severe turbulence that can cause the aircraft to have difficulty maintaining airspeed. I’ve been in severe turbulence. I’ve been fortunate that no one was injured.

The severe turbulence situation that I recall most vividly was we lost about 20 knots of airspeed at altitude at 35,000 feet. That’s a lot of airspeed to lose. So not only were we dealing with the severe turbulence and the shock and awe of that … we had to maintain the airspeed on the aircraft so that we didn’t stall.

The most critical threat to an airplane in severe turbulence is the loss or massive gain of air speed…. You’ve got to man the controls and effectively fly it through that break in smooth air.

KAK: What is the communication around turbulence and in your circle of pilots and air traffic control? How is turbulence monitored and measured?

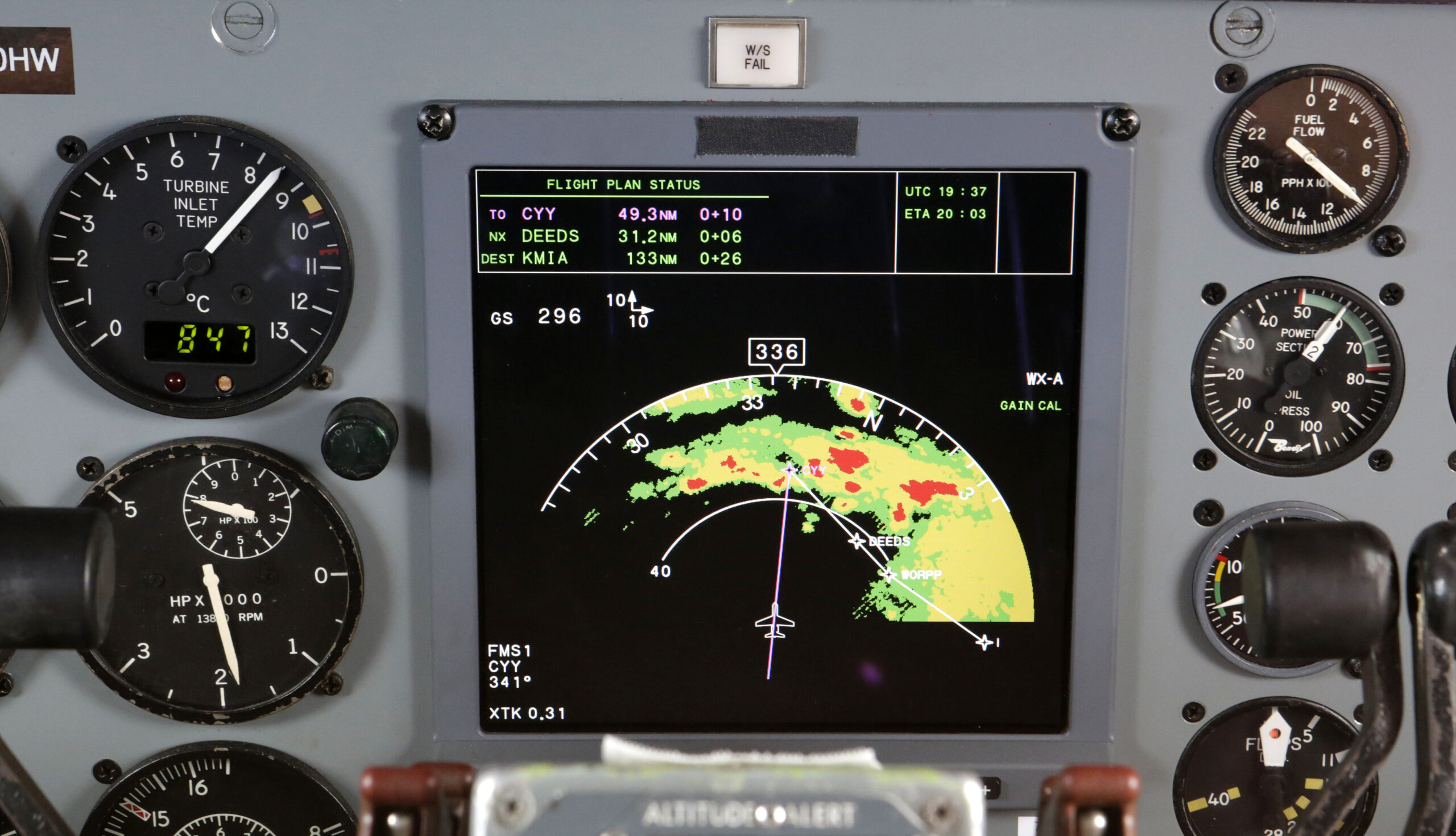

DT: I’ve been doing this for over three decades. It’s literally a completely different world. Technology obviously has moved us along in so many things, but the predictive ability based on actual reports and then overlaid into the models is extraordinary.

I have an iPad app that is crowdsourcing for all aircraft. Imagine if you had your iPad in a holder in your car, and you’re going over potholes, it sends a signal to everybody else on the road, “don’t take the left lane.” We have that on the airplanes. I use it all the time. I used it yesterday, and I can literally see live where there might be a tunnel of smooth air to descend through as we come into, say, Chicago here, or Madison, Wisconsin. It’s extraordinary.

It does not take away the seriousness of respecting Mother Nature, because surprises can happen. It can change in minutes, but it gives us an idea of what others are seeing, feeling minutes before us.

KAK: Some scientists believe that turbulence is getting worse, and there’s a researcher in England expecting clear air turbulence, which is found at high altitudes, that could triple by the end of the century. From your decades of experience, does turbulence appear to be increasing?

DT: Yes, it’s more powerful. Yes, it’s more frequent. Is this a cycle of the globe? Is this something else going on? … As pilots, we don’t really care why. We just care about how do we deal with it, and how do we keep people safe?

KAK: What protocols do you follow when you encounter turbulence?

DT: We have particular air speeds when we know the ride is going to be more difficult. It’s manufacturer guided. It’s similar to how you have potholes on the highway. You reduce your speed. It helps ease the bumps. That’s been around for a long time.

But one of the most important things is to not have that seat belt light on all the time. What does that mean? It means that when you don’t need a seatbelt sign on, that sign should come off . . . We have changed the way we communicate that seat belt sign. We fight to get that sign off so that it means something when it’s on.

KAK: As we see older and older planes flying through turbulence, are there any concerns about the wear and tear on the planes themselves? Do planes need to be made with stronger parts, more durable, to deal with a longer lifespan and the growing severity of turbulence?

DT: I think they’re made strong enough now, but they’ve got to be maintained.

You can’t just fly an airplane for several decades and do a quick check. They do have heavier checks. Those checks are often done offshore. It’s another thing we’re fighting for, to bring that back home, do the detailed checks with good oversight, not just delegated review by the Federal Aviation Administration but the FAA actually being there and saying, “Now, let me check what you just checked.”

That’s something that we’re very concerned about now, because the oversight from the federal government has been less than spectacular. Let’s just call it what it is. It’s been horrid. That is changing now, but it’s got a long way to go.