This story was produced and originally published by Wisconsin Watch, a nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom. It was made possible by donors like you.

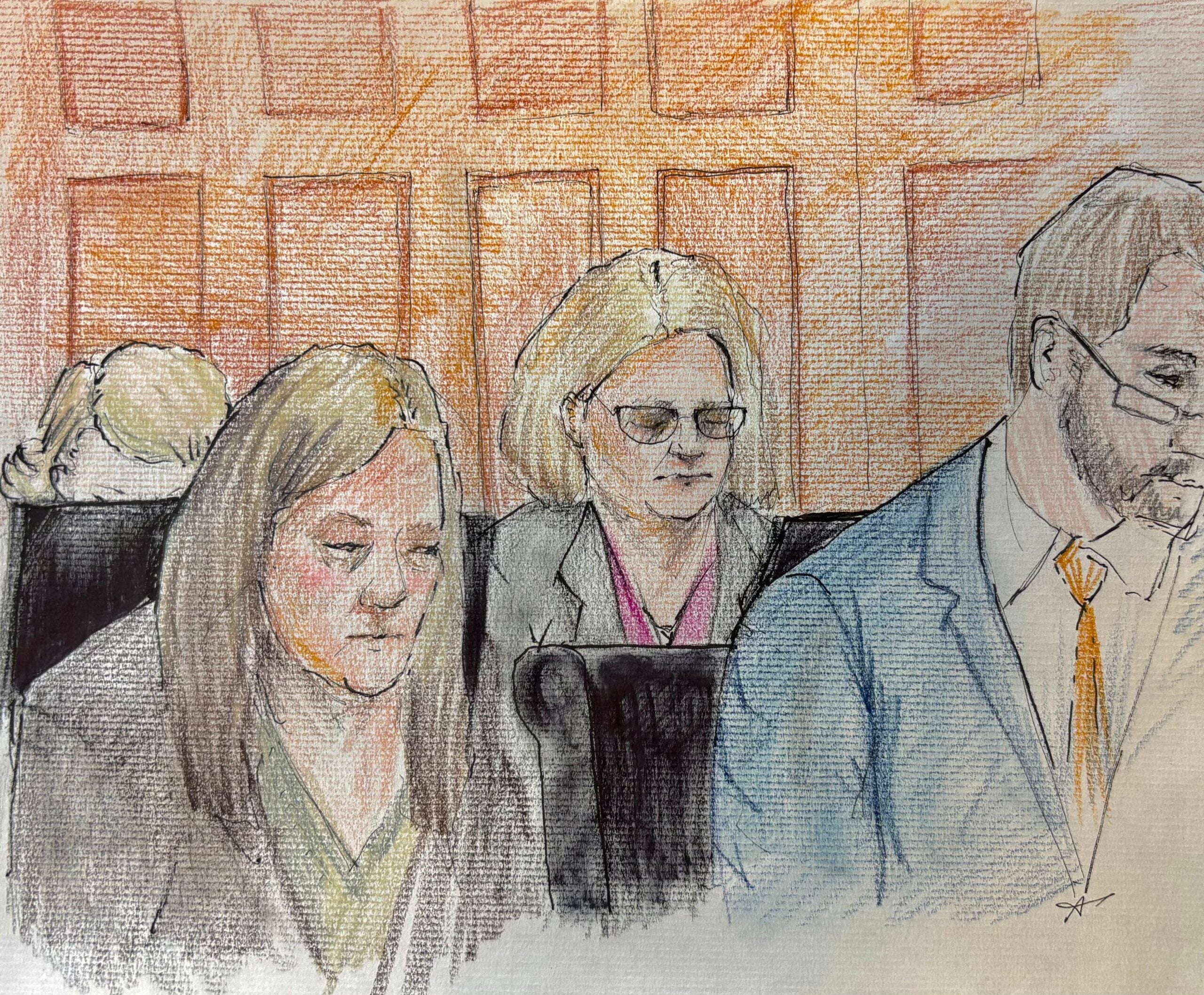

An Appleton police detective pleaded guilty to a felony for forging official signatures on search warrants used in a drug investigation and was fined $500.

During sentencing April 30, the Outagamie County Circuit Court judge noted former Appleton Police Sgt. Jeremy Haney’s dishonesty “may impugn any number of cases on which he has been involved.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But whether prosecutors in Outagamie County track dishonesty among law enforcement officers isn’t clear. Unlike the majority of counties that disclosed who committed what are known as Brady violations, Outagamie was among 17 offices that either denied a Wisconsin Watch records request or said it didn’t keep track. Prosecutors must tell defense attorneys about such violations whenever those officers are called upon to testify in a criminal case.

A Wisconsin Watch investigation seeking Brady files from all 72 counties found more than 360 examples in 31 counties of current and former Wisconsin law enforcement officers who prosecutors have flagged for dishonesty.

That’s a small fraction of the state’s 15,000 sworn officers, but also an incomplete number because of the inconsistency in tracking the information.

Another 23 district attorneys said they had no names on file, though some said in response to Wisconsin Watch’s inquiry that they would reach out to local agencies to update their list.

The lack of legal clarity has vexed defense lawyers and law enforcement officers — natural adversaries in the criminal justice system — who both say the current system can be confusing to navigate.

“It shouldn’t be the wild west,” said Jim Palmer, executive director of the Wisconsin Professional Police Association, the largest police union in the state. “Some DAs may keep a list, some may not. … And whatever the procedure that a DA currently in office may utilize doesn’t mean that any of their successors are going to do it the same way.”

So far only one state, Colorado, has attempted to create a uniform system, though law enforcement lobbyists have been working behind the scenes to change Wisconsin law to make it easier for police to be removed from Brady lists.

Varying methods and levels of transparency

Named for the landmark 1963 U.S. Supreme Court decision Brady v. Maryland, the Brady doctrine began in what became a series of federal and state precedents requiring the government to disclose evidence that could impeach the credibility of the prosecution’s witnesses.

A Wisconsin Watch analysis found the way district attorneys collect and manage Brady information — if that happens at all — is up to individual officeholders, and the methods and transparency vary.

Ozaukee County District Attorney Adam Gerol said there are no active officers in his county subject to Brady disclosure, so there isn’t a current list. He relies on agencies to disclose if an officer giving testimony has ever been dishonest, but he has “never had a need to periodically request this information.”

In Green County, District Attorney Craig Nolen regularly sends out a three-page memo to law enforcement detailing the legal importance of full disclosure and noting “it is neither fair nor reasonable to expect prosecutors to risk their law licenses to hide another employee’s intentional negative conduct.”

Nevertheless, Nolen refused to publicly release the names of the officers he has on file, citing case law that often places a prosecutor’s files beyond the reach of open records requests.

Waukesha County, District Attorney Sue Opper initially denied Wisconsin Watch’s records request for a Brady list saying “no records exist.” But upon follow-up she admitted the office does have Brady letters for several individual officers on file and produced 11 letters after deadline and shortly before publication of this story.

The lack of consistency and transparency on Brady information has long frustrated watchdog groups seeking to hold police agencies accountable for officer misconduct. Defense attorneys are also wary of prosecutors leaving it up to law enforcement agencies to self-report.

“Some prosecutors are more diligent about tracking it than others,” said Adam Plotkin, a legislative liaison in the State Public Defender’s Office.

‘You can’t fart without somebody catching it’

Prosecutors in sparsely populated counties described an informal approach to flagging dishonest officers but insisted they take oversight seriously in communities where people know each other.

“In Buffalo County you can’t fart without somebody catching it,” District Attorney Tom Bilski said.

He acknowledged in the past he witnessed instances of flagrant dishonesty among law enforcement, but the roughly 20 officers in his county are part of a new generation of police who he believes are more ethical. He said he and his assistant read every police report that accompanies a criminal complaint looking for evidence of dishonesty.

“If I have any inclination that an officer’s gonna perjure themselves on the stand, I will immediately put them on a list, and they’ll know that and I’ll dismiss the case,” he said.

Longtime Kenosha County District Attorney Mike Graveley said past practice was not to keep a list but rather a voluminous paper file for any documented dishonesty self-reported by police officers who were asked to complete a questionnaire.

“We did no analysis,” Graveley said. “We just simply collated that information and collected it. And then if somebody sent us an open records request, we sent out all of the names.”

But several months ago, his office began scrutinizing each name and making its own call on whether missteps should rise to the level of disclosure to defense counsel.

“Any individual that we felt did not meet the standard of something we would need to disclose to defense counsel as exculpatory evidence,” Graveley said, “that person is no longer included in any list.”

Other district attorneys either didn’t track dishonest officers or were unwilling to share names with the public.

Outagamie, Waupaca, Door, Manitowoc, Pierce, Polk and Rusk counties all rejected the records request with responses that used the exact same wording.

“My concern is that such information will potentially be abused by entities that may have an agenda that is, perhaps, not foreseen by your organization,” Polk County District Attorney Jeffrey Kemp wrote in response to Wisconsin Watch’s appeal to his denial for records.

Rusk County District Attorney Ellen Anderson, who was appointed by Gov. Tony Evers in 2022, reversed her initial denial after being contacted by Wisconsin Watch and affirmed her office has no current Brady listed officers or policies or procedures in place.

Some jurisdictions more diligent than others

The Dane County district attorney in Madison released a list with 25 names on it from 10 law enforcement agencies with the caveat that not all officers may still be employed by that department.

The state Department of Justice has resisted sharing its list of currently active law enforcement officers, making it difficult to cross-reference names.

The Milwaukee County District Attorney’s Office — which oversees more than a fifth of all sworn officers in the state — released a list with 150 names going back 20 years listing criminal charges against the officers.

However, the county declined to release “records relating to individuals on the list who were referred for prosecution but not charged,” wrote Milwaukee County Deputy District Attorney Karen Loebel.

In Brown County, prosecutors in Green Bay released a list with 16 names but with no context on why they were included or whether they were still employed.

“For more specific information about each, I would refer you to the respective agency where the officer is or was employed,” Brown County District Attorney David Lasee wrote.

The list included no dates or corresponding agencies.

Colorado law creates statewide standard

Legal experts say Wisconsin’s example of uneven transparency standards is common nationwide.

“It’s completely and sadly normal,” said Rachel Moran, an associate law professor at University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minneapolis, who has criticized systemic failures to enforce Brady rules.

Only Colorado has a law requiring the maintenance of Brady lists and explaining what those lists should look like, she noted.

The law established a six-member oversight committee that includes a majority appointed by police groups and prosecutors who are empowered to decertify officers for “untruthfulness.” It also mandated that officers flagged for dishonesty be tracked in the public-facing database.

Colorado’s system also enshrines a notification requirement for officers before they’re placed on a list and lays out a process for them to petition removal.

A mechanism that would allow officers to challenge and be removed from a Brady list has been a priority for Wisconsin law enforcement groups, which records show have been quietly lobbying on the issue since last July.

“I have come across incidents where individuals have been wrongly accused of things,” Badger State Sheriffs’ Association President and Dodge County Sheriff Dale Schmidt said. “They never had the opportunity to have that due process to at least share both sides of the story.”

Defense attorneys are skeptical of how an officer flagged for dishonesty could later be delisted without running afoul of the constitutional principle that a person’s past dishonesty should be disclosed.

“The mere passage of time doesn’t change the fact that it’s still exculpatory,” said Dean Strang, a veteran Madison defense attorney who also teaches at Loyola University Chicago School of Law.

Wisconsin Watch inquiry sparks conversations

The Wisconsin Department of Justice doesn’t have a statewide Brady list and doesn’t provide uniform guidance to counties on how to maintain Brady information.

Several district attorneys told Wisconsin Watch they only reached out to law enforcement agencies for a list of dishonest officers after Wisconsin Watch asked for their list.

Palmer, the police union head, said the Colorado model is better than Wisconsin’s nonexistent standard. Law enforcement wouldn’t necessarily object to having the lists be made public, he added.

“The public does absolutely have the right to know what officers are on Brady lists, but they also ought to have some confidence that those determinations are made appropriately,” he said.

The Public Defender’s Office would like to see a consistent standard but Plotkin, its legislative liaison, said it would need to see the proposal.

“Uniformity is helpful if it lands on the side of providing the information, making it available,” Plotkin said. “Uniformity would not be helpful if it essentially provides a shield from accessing that information.”

The lack of statewide standards or oversight from DOJ leaves prosecutors to make judgment calls that have life-changing ramifications based on one person’s word against another.

“Law enforcement officers get an enhanced presumption of credibility — it’s just the way of the world,” Plotkin said. “And so when you have that heightened presumption of credibility, there should be heightened scrutiny.”

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.