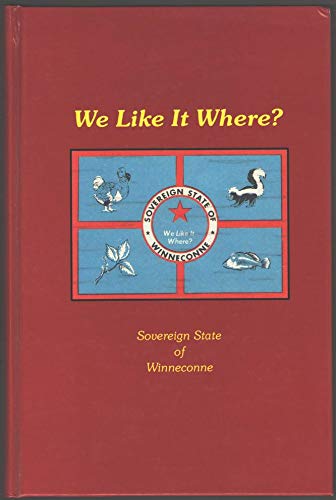

The year was 1967. The place was Winneconne, a small village and self-described “fisherman’s mecca” in northeast Wisconsin — according to Polly Zimmerman’s book, “We Like it Where?: Sovereign State of Winneconne” — at the confluence of two lakes in east central Wisconsin.

The problem was that Wineconne had been accidentally left off that year’s official state highway map. In the spot where the village should have been, there was just “a blank little circle,” Zimmerman wrote.

Her book is as much about the hugely successful marketing of Winneconne as it is about the place itself.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

In an era when people relied on physical maps, Winneconne had good reason to worry about losing tourism revenue.

The solution was simple. Local leaders wrote a letter to the governor of Wisconsin, Warren P. Knowles, requesting that the maps be revised to include Winneconne.

But Gov. Knowles replied that redrafting the maps simply wouldn’t be possible – though he insisted that the village would “definitely appear on the 1968 map.”

That was not good enough for Winneconne.

The governor got way more than he bargained for with the tiny village’s bombastic response: a nationwide contest to determine how to get Winneconne back on the map, boosted by congressional Rep. William Steiger, Zimmerman said in the book. An all-expenses-paid weekend trip to Winneconne was the prize.

The village got over 1,000 responses to its “Here’s How to Put Winneconne Back on the Map” contest, including:

- “Change the name.” -T.G. Nicholas, Chicago, Ill.

- “Let me win a weekend and I’ll advertise it.” -Viola Salmi, Chicago, Ill.

- “Have topless go-go girls minimum 46.” -Donald Sukach, River Grove, Ill.

The winning entry was far more drastic than all of those.

It came from Janice Badtke and Kay H. Klipstine, native Wisconsinites who were congressional aides and roommates in Washington, D.C. The pair submitted six entries to the contest, all of them rather hawkish. Their ideas, Zimmerman wrote, included a public map burning, relocating the CIA headquarters to Winneconne and putting pirates on the Wolf River to extract levies from local boaters.

But the winning entry went a step further. Several steps further. It read:

“Winneconne secedes from and declares war on United States, proclaiming Republic of Winneconne. Authorities seize Federal property, detaining Postmaster as enemy alien. Request UN peace mission to prevent border hostilities; preserve Winneconnian territorial integrity. Close Port of Winnecone to U.S. shipping, enforcing 12-mile limit.”

The contest judges looked at this proposal to steal, kidnap and militarize, and they thought, “Yes.”

Preparations to secede got underway. In the end, Winneconne – which was, after all, a village of fewer than 2,000 people – stuck with the secession part, and decided to forgo military action.

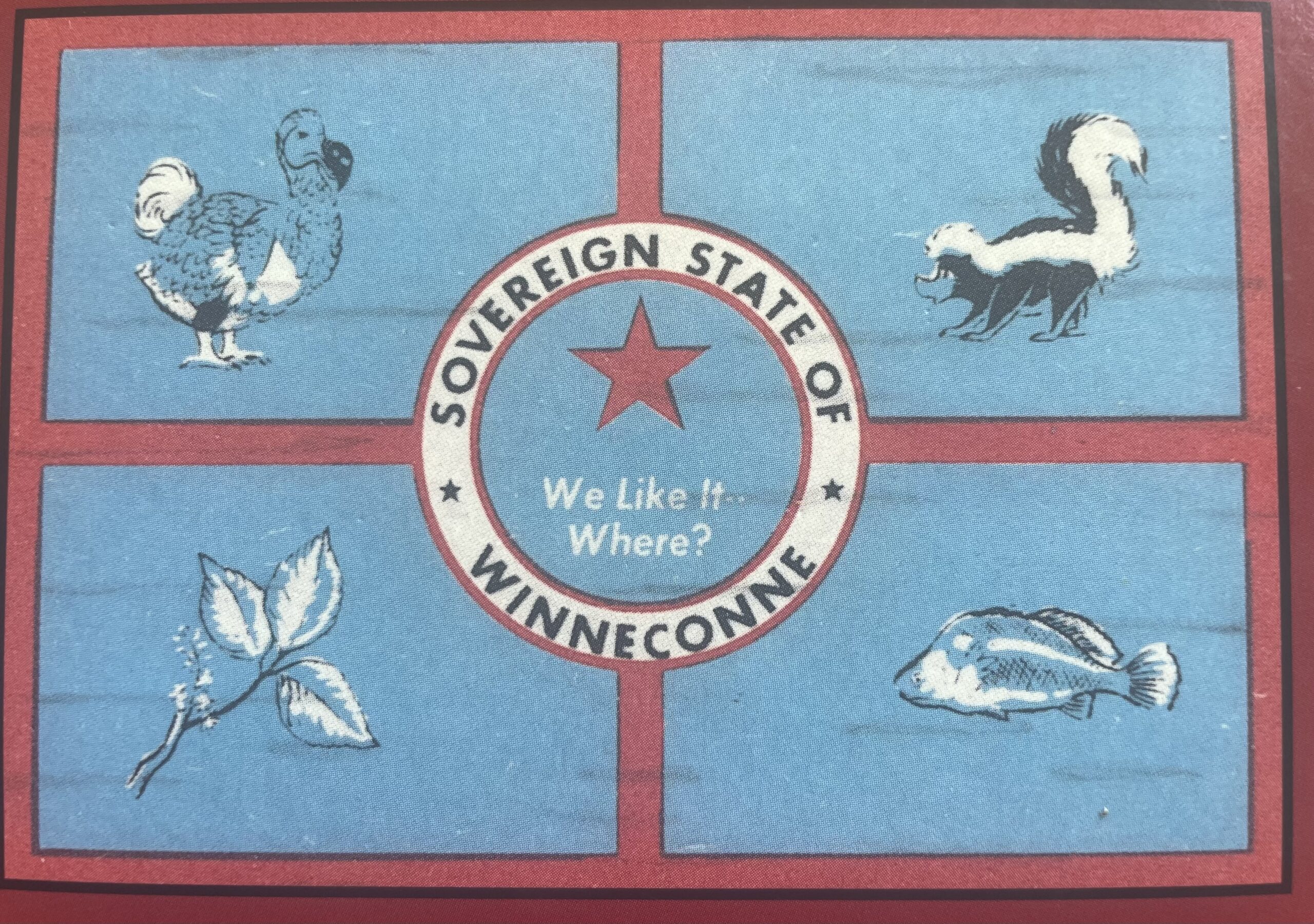

An official declaration of secession was delivered to Gov. Knowles, and on July 22, 1967, Winneconne threw a huge celebration with parades, boat races, community breakfasts, a one-day toll bridge and more. Residents lowered the state flag and raised the new sovereign’s banner.

Officially, the secession lasted less than 24 hours. But it’s been celebrated nearly every year since at the Sovereign State Days festival.

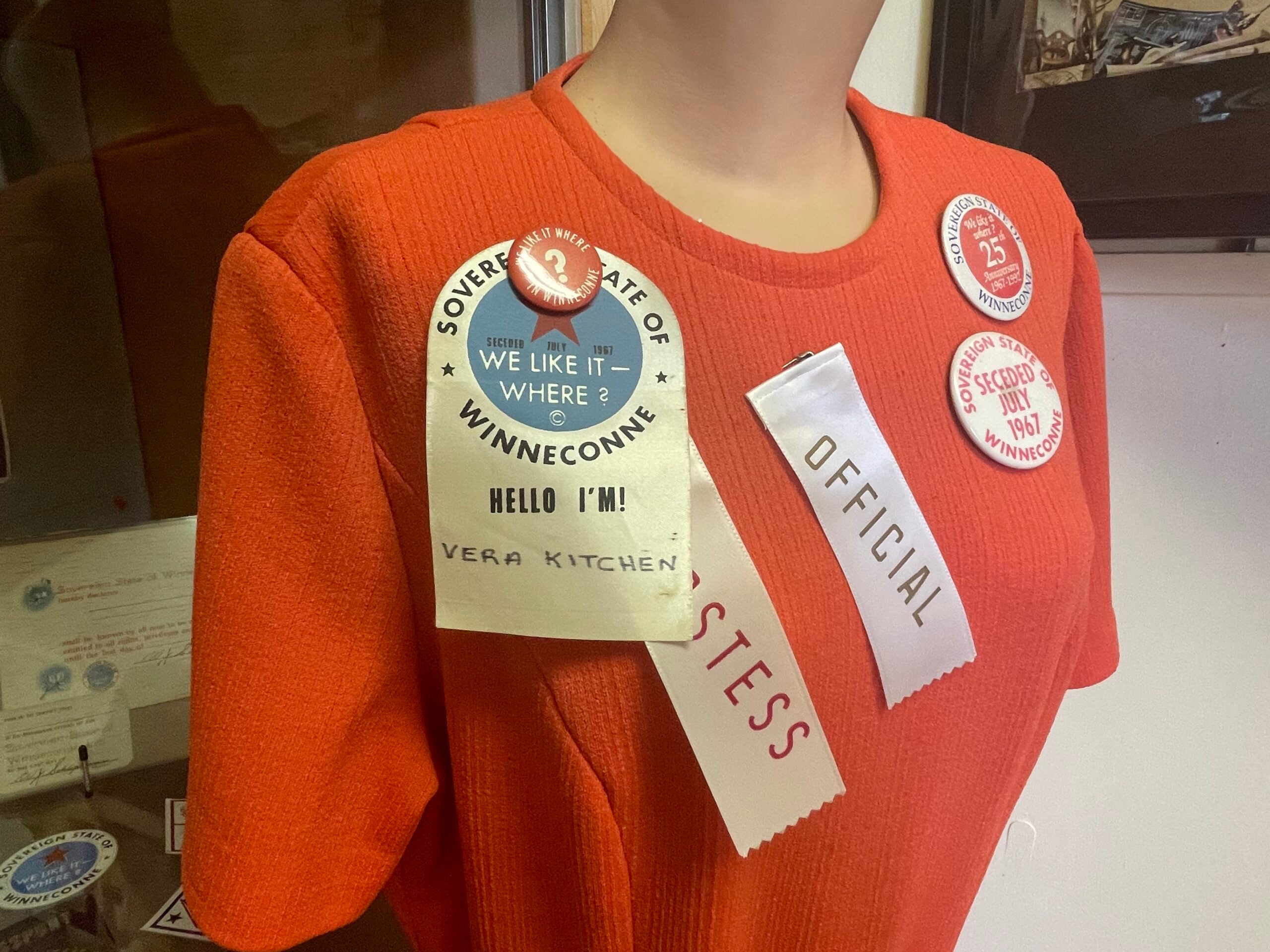

It took a lot of people to make the festival happen, but Chamber of Commerce President Vera Kitchen was the mastermind behind it all.

Kay Larson and Lori Meyerhofer-Fisher, both of whom are Kitchen’s nieces, told “Wisconsin Today” described her as strong-willed and extremely capable, an endlessly energetic workaholic and a woman way ahead of her time — the characteristics legends are made of.

Winneconne’s secession was, at its core, a brilliant PR stunt, one that’s stood the test of time. Zimmerman writes about the “media deluge” brought on by the village’s contest and subsequent secession. Winneconne went viral before going viral was a thing.

And it turns out that Gov. Knowles was in on the joke the whole time. Knowles was the honorary chair of the “How to Put Winneconne Back on the Map” contest. He got the ultimate say in who won.

Knowles happily played the role the village cast for him — that of the remorseful politician. Winneconne sent the governor detailed instructions on how exactly the “secession” would go down.

After Winneconne raised its flag, the governor called Kitchen and Village President Jim Coughlin to “express his regret on the part of the State of Wisconsin that the village found it necessary to take the secessionistic action and assure the village that they will be on the 1968 Map and that they will be represented on U.S. 41 at the 110 turnoff.”

The phone call, naturally, would be broadcast on Winneconne’s PA system for all the villagers to hear.

The State Highway Commission’s mistake, and Winneconne’s response to it, made national news. One article notes that the mayor of Valparaiso, Indiana, invited Winneconne to become a part of his state.

In her letter congratulating the contest winners, Zimmerman noted, Kitchen included a copy of the Winneconne News and wrote gleefully of the press the town was getting:

“You may have noticed that the judging event was released through the AP wire service and was reproduced in many daily papers, radio and television media throughout the United States. Your visit here should result in another explosion of news and photos.”

Sovereign State Days was the jewel in Kitchen’s crown of offbeat, attention-grabbing marketing campaigns. Later in her life, she moved to California and got involved in real estate. She came up with goofy, offbeat advertising campaigns, like one that featured her riding a motorcycle, “revving up the motor” to lead buyers to her development.

Before heading up the local Chamber of Commerce, she worked for the Red Cross teaching English to the Italian wives of American soldiers. She taught in a one-room schoolhouse. She also owned and operated a restaurant, owned an ice cream shop as well as a gas station where she did oil changes herself, Larson and Meyerhofer-Fisher said.

“You look at that time in ‘67. How many women were even in that realm?” Meyerhoffer-Fisher told “Wisconsin Today.”

“She was… trying to be different, to stand out. And, of course, she did,” Larson added.

Kitchen died in 2012 at 98. Her legacy lives on in her community.

Even though Winneconne has been back on the map for nearly 60 years, Winneconneans gather every summer to celebrate the holiday that Kitchen started and the history that makes their little village unforgettable.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.